IN/FIDELITY

From the Editors

Dear readers,

We are the editors of this issue of Exchanges: Journal of Literary Translation, IN/FIDELITY. We designed the call, read and reviewed all submissions, and worked with each translator to edit and present these pieces, as has always been our process. This issue is the work of an incredible array of authors and translators. This letter, it must be noted, is not meant to speak on behalf of them. We speak instead to our own experiences of putting this together.

Exchanges’ themes are typically abstract, and, in that sense, IN/FIDELITY falls neatly within the realm of literary publishing we’ve been producing for the last 36 years. This issue is far from predictable, however.

Translations are often discussed in relation to fidelity—whether that’s to an “original text,” an “original intention,” or some other criteria—and so fidelity becomes an imagined yardstick against which translations are measured and given merit. Beyond translation, the yardstick of fidelity also evokes tensions surrounding power, trust, expectation, and desire.

For our issue on IN/FIDELITY, we called upon translators from around the world to respond to this yardstick and to play with it: spin it upside down, twirl it about, and tamper with its markings. Through this investigation, we hope to emphasize the creative potential that is inherent in translation. We ask: how can translation change the ways we imagine in/fidelity, and our understandings of the worlds we live in?

+++

In this issue, you’ll be transported by Serbian, Farsi, Japanese, Yiddish, Spanish, Bulgarian, Portuguese, French, Chinese, Vietnamese, Dutch, and Russian languages—the work of fourteen translators or translator teams that span twelve languages, each opening a portal to new worlds. We invite you to enter and explore.

“Arrow and Sponge,” a short story by María Laffitte, translated by Tess Rankin, “plays with scientific ideas without adhering to the genre expectations of science fiction [and] shows us how knowledge and imagination of all stripes can shape our understanding of women’s experiences.

Ajla Dizdarević worked with Serbian poets Milica Špadijer and Uroš Bojanović to create translations that “maintain the essence of their original work while ensuring this essence is accessible to an Anglophone audience” within worlds of grief, doubt, and war.

Terry Hermsen and Sydney Tammarine translate a poem by Christian Formoso, a poet whose “modern Chilean verse shares the stage with fifteenth-century Castilian Spanish, [requiring] n English that equalizes the contemporary and historical.”

In “The Fist,” translator Mordecai Martin creates “A Trot, A Translation, And An Explosion” of Eliezer Shteynbarg ‘s Yiddish poem. Unfaithful? Traitor? “All of these accusations are familiar to the experimental translator,” Martin writes.

Jacob Mattke translates from French an excerpt of Capucine Delattre’s From Her Blood, extending the author’s “dare to question such an unquestioned element of society as the mother-child relationship.”

Cristina Ferreira Pinto-Bailey translates two pieces of Portuguese flash-fiction by Carla Kinzo, whose “writing opens a space of tension wherein the balance between fidelity and infidelity to the original text encourages and demands the translator’s creativity.”

Kexin Song translates a selection of Chinese poet Ding Cheng’s poems, which bring together the environment, technology, and literature, opening up “an interdisciplinary experiment that integrates the human world with its orangutan counterpart, pushing the boundaries of poetry writing in the midst of the extinction crisis.”

Viktor Shirali wrote “when Russian poets had begun the labor of repossessing their language in the wake of the official diction of Soviet life,” and J. Kates “repossesses” five of his poems into English.

Farsi poet Forough Farrokhzad centers herself in her works as the subject who experiences love, taking an unprecedented route that Monir Gholamzadeh Bazarbash translates “to convey the immediacy of emotions.”

The poem Allison deFreese translates by Janil Uc Tun, “The cemetery,” is from Gentry, a collection structured to follow both the Maya Calendar and Dante’s Divine Comedy. In this “lyric bildungsroman,” Uc Tun critiques gentrification, colonialism, human trafficking, and Indigenous suppression.

Stoil Roshkev’s “That's Not What Poets Are,” translated from Bulgarian by Rosalia Ignatova, “is a poem that rattles, mocks, and sings… its wild cataloguing builds momentum through strings of phrases where sound often precedes sense.”

Annelies Schoolderman translates Nina Polak’s short story “Country Life” from Dutch, stating boldly that “a translator need not be a ghost.”

In translating Đặng Thơ Thơ’s “Chrysanthemums,” Quynh H. Vo “felt the pull of fidelity and infidelity as a kind of erotic tension,” as the story’s queer love isn’t smooth or possessive. “So, too, must translation resist the illusion of seamlessness.”

Kinji Ito translates Japanese author Takamura Kōtarō and pursued “productive infidelity,” a strategy that “transforms without erasing, adapts without flattening, and foregrounds ambiguity, humor, and authority to make the dialogue between tradition and modernity.”

+++

We celebrate these authors and translators who, like us, see translation not as a passive act of “faithful” or “unfaithful” transfer, but as art, interpretation, activism, commentary, transformation.

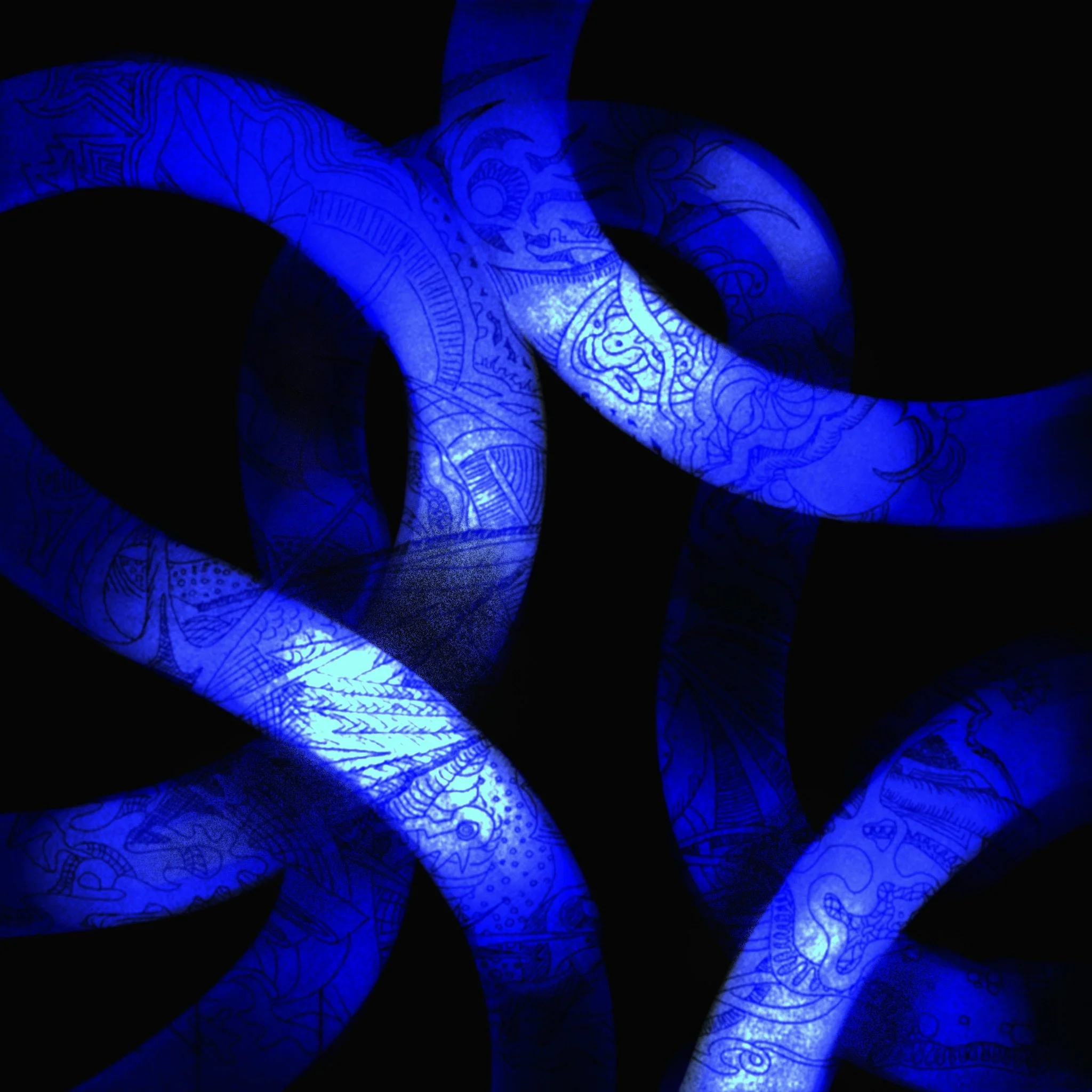

Special thanks to our issue artist Eylül Doğanay, a deep friend to translation, for generously sharing her art with us to feature alongside the pieces. Her series illustrates the interconnectedness of humanity: our shared stories, languages, hearts. We’re grateful to be able to place so many of her incredible artworks in conversation with our translated pieces.

We’re proud of this issue, and grateful to all of our contributors, readers, and friends for their support and trust (and dare we say, faith) throughout this foray into the in/fidelity of translation.

Exchanges Editorial Team, 2025-26