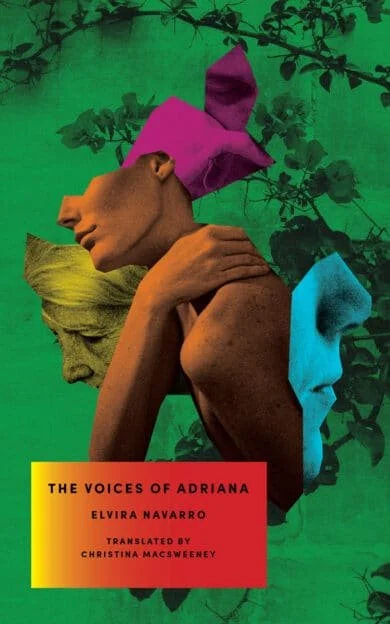

Review: The Voices of Adriana by Elvira Navarro

Translated by Christina MacSweeney

Review by Emma Murray

The Center for the Art of Translation, 178 pages, $17, paperback

Adriana, the protagonist of Elvira Navarro’s third novel, The Voices of Adriana, translated by Christina MacSweeney, is an existential thirty-year-old obsessed with voices—the voices of the characters she writes in her stories, of her mother and grandmother, of her childhood home, of the people backgrounding her lonely world.

Voices are sounds with meanings. A range of pitch, but also an expression of logic, as in syntax and emotional inflection. Where do voice and thought intersect? Diverge? Adriana’s mother, speaking at one point from beyond her grave, stops herself abruptly, saying: “This isn’t a thought my voice should express. My voice has to be unaware of such things.”

Of what is a voice aware? Do we have enough awareness around voices?

Throughout The Voices of Adriana, Navarro drives her characters, scenes, and stylistic choices toward answering these questions. Divided into three parts—The Father, The House, and The Voices—each section approaches Adriana’s world differently; first, through a close third-person narration of Adriana’s present life interwoven with her fictional stories; second, via her memories and family history; and third, through direct voices from her maternal line.

In The Father, Adriana is grieving her mother’s slow death to cancer while caring for her ailing father, who suddenly embarks on an online-dating bender. In the second section, The House, her grandmother’s house foregrounds the story; Adriana twists her stories and folds memories in on themselves, trying to understand what is connected to what in her past. It’s this introspection that leads Adriana straight to her mother’s and grandmother’s voices, which, in the third section, The Voices, come in direct form, like a screenplay.

This slow zoom-in on Adriana’s psyche—moving from the external to her internal worlds—illustrates Navarro’s commitment to interrogating how people, and their voices, are formed.

Translators, of course, can’t help but consider the formation of voice in and around storytelling—their very goal is to understand and underscore in a text all the elements we’ve heretofore named: meaning, affect, pitch, sound, logic, syntax, emotion. Bring these from Language A into Language B.

Given the sections’ distinct narrative styles, some translators might have taken the opportunity to underscore Navarro’s meditation on voice and narrative form by sharpening the contrasts between character voices, especially in The Voices, given the Daughter, Mother, and Grandmother. While their similarities could reinforce the inheritable nature of voice, the voice-stretching Spanish displays a vibrancy greater than the resemblances rendered in English.

Beyond voice, time also stretches and bends in this novel, and some transitions felt more challenging to follow, as when Adriana oscillates between her memories and her present-time introspection:

In recent years, she’d very frequently found herself mentally touring the rooms of that house because she had a precise memory of them that was her safeguard at any time, in any situation.

En los últimos años se había visto, en innumerables ocasiones, recorriendo mentalmente las estancias de la casa, pues guardaba de ellas una memoria exacta que la salvaguardaba siempre, a toda hora y en cualquier circunstancia.

In Navarro’s sentence, the punctuation guides readers more gently through the changes in temporality and reflection, and the English more laboriously hinges on prepositions. In other sections, an inconsistent register can feel distracting, like in Adriana’s first-person narration, when she meanders from phrases like “totally wiped out” and the use of multiple contractions, to “seemed to perceive a truth there: that more than individuals, we are points of confluence for everything that precedes us” within a single paragraph.

A voice—what is it again? Some combination of sounds and words—how someone communicates—but also how a person’s lungs pump, mouth shapes, fingers type, ear hears, eyes read, neurons fire, yours, theirs, connecting and firing and connecting again, no?

It’s often said good writers are good listeners; if so, good translators must not only listen well, but read well, too—with eyes and ears tuned deeply, prismatically, critically, and generously to voice in a text. Close reading brings understanding; immersion teaches flow, vibrancy, and sensitivity to elements within and outside ourselves.

Throughout The Voices of Adriana, as Navarro depicts and dissects Adriana’s voice, ergo her psyche, the novelist is asking readers to do the same unto themselves. How does your voice connect to your psyche? Can these connections be translated?

-

Emma Athena Murray is a writer, editor, and translator of Spanish literary works. She is the co-editor-in-chief of Exchanges.

After seven years as a journalist reporting at the intersection of geography, public policy, and social justice, she pivoted into an MFA in Literary Translation and the truth-telling spheres of world literature. With a double-BA in Philosophy and English from Brown University, she continues to interrogate the world through written words. Her research interests include both contemporary and 16th-17th century female voices from Latin America; how feminine rage manifests in literature; the alchemic powers of translation; and autotheory as literary craft.