The Interview: Jack Hargreaves, translator of Hu Anyan’s I Deliver Parcels in Beijing

Conducted by Fion Tse

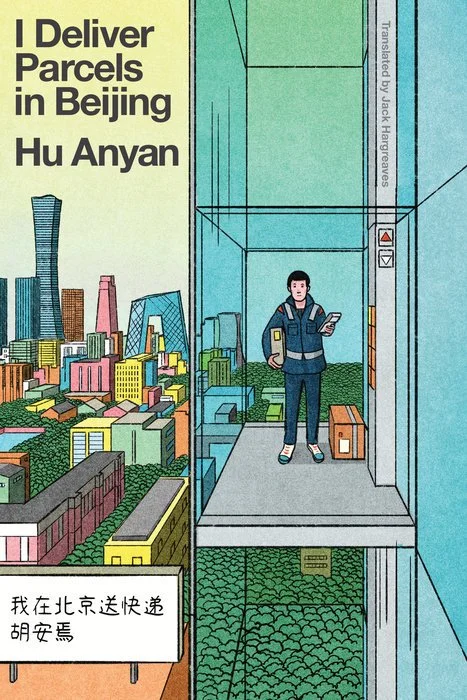

Astra House, 336 pages, $27, hardcover

Jack Hargreaves is a Chinese-to-English translator from Yorkshire. His translations, both literary and academic, have appeared in Asymptote, Words Without Borders, LitHub, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. Jack is one of the translators behind 李娟 Li Juan’s Winter Pasture and 柴静 Chai Jing’s Seeing. Most recently, his translation of 胡安焉 Hu Anyan’s I Deliver Parcels in Beijing was published by Astra House in October 2025.

Fion Tse (she/they)

is a translator working between English and Chinese (Cantonese and Mandarin). She is currently pursuing an MFA in Literary Translation at the University of Iowa, where she is also co-Editor-in-Chief of Exchanges. Her work has been published in ArtAsiaPacific, Asymptote, Full Stop, World Literature Today, and more.

Fion: In your translator’s note, you mention the many different versions of this book that exist in Mandarin Chinese, as well as some passages that were written exclusively for the English translation. What was that collaboration like? How do you view your role as a translator-editor, or perhaps a translator-curator?

Jack: It was a delight to be part of the collaborative effort to bring this work into English. My earliest involvement was the first conversation the agent and US editor, Patrizia van Daalen, and I had after we’d been introduced to each other, in which we passed suggestions back and forth for recent books from China that had caught our attention. Parcels was one we had both clocked. We chatted about it a little, then weeks later the book topped the yearly roundup of the most popular and highly rated books for 2023, on Douban Reads (China’s sort-of equivalent of Goodreads), and she asked me if I’d put together a sample for the publisher to consider. The conversation really just continued from there, throughout the process. I would complete a section and send it to her, sometimes with questions or comments, and she would respond and ask questions of her own. She might suggest moving a paragraph elsewhere, or I’d run it by her if a sentence felt like it could be majorly condensed or a repetitive passage could be omitted. It’s fairly standard that I signpost for editors any departures from the source text that feel, maybe, bold, but it’s rare that I consider those changes excessive, otherwise I wouldn’t make them. I’m not asking for permission with these comments, just pointing out a thought process and laying a paper trail. This, I suppose, is where my editorial role comes in, whereas the curatorial part of the work to me is more the deciding which books to translate and selling publishers on them—playing a part in shaping the Chinese-language-literature-in-English-translation ecosystem.

But back to Parcels, and asking authors questions. This I usually do to double-check what exactly an author was intending by using a particular turn of phrase in a particular place, something like that. To clarify meaning, basically. We sent some to Hu, this book’s author, a handful maybe. But generally, Patrizia and I were able to clear up any uncertainties about the effect or precise nuance of an expression by talking it out together, since she also reads Chinese, which obviously not every editor at an English-language publisher does. It was Patrizia who suggested to Hu that he add some extra paragraphs to the end of section one, for me to translate. There, in the Chinese, he explains he quit his job and moved to Beijing for personal reasons, and Patrizia felt, if Hu was comfortable doing so, that readers might appreciate him divulging more about those reasons. Hu was very conscious of what he wanted to include and keep out of the book about his personal life and relationships outside of work. The book was always intended as a work memoir. But he was happy to do it.

A further layer (or two?) of collaboration that I found really enjoyable and productive involved the Finnish and Dutch translators, Rauno Sainio and Silvia Marijnissen. They were translating the book at the same time as me, in the hope of getting out versions in their respective languages before or around when the English was going to be published. Unfortunately, I can’t read either Finnish or Dutch, so the limit of my contribution was sending them sections as they were completed, for them to read through and compare with their own. But they were fantastic first readers and assured me they also found it a very useful activity.

One really wonderful thing about this book is that it feels like a work of collaboration that started way back when Hu first posted those early sections online. His first collaborators being everyone who read them, everyone who commented, all the people who jointly created the enormous buzz that built around the individual essays and Hu himself; then the editors who approached him about fleshing out what he’d already written and putting down his remaining work experiences for a print publication, and so on. This English translation is just one extension of this long collaborative project that has branched in various directions.

Fion: You also discuss navigating the balance between audiences who are more familiar with Beijing and its Mandarin Chinese, and audiences who are not. I love your assertion that “the language of real estate can be quite bombastic and ostentatious when it wants to be, so why shouldn’t these translations be, too?” To that point, there are several moments in the text that sound highly anglophone (the phrase “sniff at” makes an appearance) alongside others that remain in pinyin with a gloss (“erguotou”, for instance). These moments are also representative of voice and characterization. How did you end up striking that balance between “authentic and realistic” language, as you put it, and finding Hu’s voice in English?(On that note, there’s a gradual shift in Hu’s voice and language as he becomes more jaded across the course of the book. I was so impressed to see it working on the more microscopic level of individual sentences, too!)

Jack: I’m glad that resonated with you as a fair justification for approaching the place names how I did. I know some readers have been disappointed they can’t easily look up the various locations Hu describes. But I couldn’t bear all the long strings of pinyin (the official phonetic spelling system in China) that would have allowed them to. I wanted the book to be easy to read, at the sentence level. Easy for who to read is, of course, the natural next question, given “erguotou” isn’t the most straightforward word to wrap your tongue around if you don’t speak Mandarin Chinese. But it can be parsed and, critically, is very readily searchable online. Plus, most everyone who does read Mandarin will recognise the word right away (I think?). And what’s more, there’s a gloss, like you pointed out, so readers don’t even need to look away from the page to know, at least vaguely, what “erguotou” is.

While I’m on the topic, I was surprised when one reviewer complained about the lack of concessions in the translation for non-Chinese readers, because he’d had to look up what Singles Day and Double Twelve are (they’re the enormous, like inconceivably large, online sales and shopping events that happen every year). All the information about them that’s in the previous sentence is also in the book in some form or another, so I’m really not sure how big a gloss he needed to get what was going on. I suspect what he was hoping for was a different book.

But to answer your question: my aim is for the whole translation to come across as authentic and realistic. By which I mean believable. As in, believable as something someone would write or say in the context of this kind of work, this kind of writing. And more specifically, something this narrator would say in such a context. That to me is Hu’s voice in English, regardless of the composite parts; though of course those parts also, ideally, help to make the voice believable. So, I’m basing a lot of his voice on the Chinese and how that feels to me (the effect it has) when I read it, and on trying to recreate that same feeling, or a close approximation of it, in English. But also sometimes I’m going with my intuition and, to me, it’s perfectly reasonable that someone who knows the word “erguotou” might say “sniff at”. We live in a very cosmopolitan world; Hu lives in a very cosmopolitan world, and he reads very widely. His tone might be casual, understated, unaffected, but you can occasionally spot the influence of other writers he’s read (many of them anglophone).

Fion: This book topped the charts when it came out in 2023—I remember how it took the internet by storm! I’d love to hear about what drew you to this book personally, and what made you want to translate it into English.

Jack: It sounds like I came to the book the same way you did. The conversation and excitement around it online was impossible to ignore. There was so much noise. It’s easy to see why, with the subject and timing of the release. I missed the initial buzz when two of the chapters were first posted as standalone pieces, so I can’t speak to that, but the print publication came pretty much straight after years of Covid lockdowns and restrictions in China, which catapulted into the spotlight a sector of society that was rarely heard from in the media or mainstream culture. All the people who had been keeping the country running—not those at the top, but those on the streets and in the factories and logistics centres and, of course, hospital wards—had everyone else all ears to hear from them, to know what that time and their work beyond it were like. The same thing happened here in the UK, just on a smaller scale. I remember reading Ghost Signs by Stu Hennigan around then, which is a semi-diary about his experiences volunteering to deliver food parcels and medication to self-isolating individuals and families in Leeds in the spring of 2020. It’s a stark, shocking account of poverty and struggle, but it’s also very touching. It felt, and still feels, like an incredibly important book.

While I know Parcels isn’t necessarily a “Covid book”, people who do the kinds of work Hu has done and portrayed remain forever vital to the everyday operations of not only society, but of everyone’s lives. And they’re humans, with stories to tell. Humans whose livelihoods, like mine, are under threat from automation. The book is timely for all these reasons. Not to mention Chinese literary non-fiction isn’t often translated and published in English (unless it’s a memoir about the author’s childhood in the countryside and their family history). So, it was a good option for bibliodiversity, too. And I knew there was a market. Just look at how well Nomadland was received. And now, just recently, we’ve had Souleymane's Story come out, too.

Fion: Switching gears, I’d love to pick your brain about your academic translation work, too. What are some differences between translating academic versus literary works? (I’m particularly interested in issues of craft—like your practical approaches, research process, or how you land on a voice!)

Jack: Although I still supervise student projects, it’s a few years since I’ve done any academic translation myself, so I’ll keep this answer short, as I’m too out of practice to know the ins and outs of what my process might look like now. Scanning your question, my brain spat out a response that is as much about similarity between those two modes of translation as difference. It’s about research, and also about landing on a voice for a book.

Most of my academic translations were in philosophy and religion (lots of Buddhist stuff); and second most were in history, archaeology, architecture and art. Invariably with all of these fields, I knew the topic in nowhere near the detail of the writer. So research was essential; it was the bulk of the work, in fact. For me, that just looked like a lot of (frantic) reading. Trying to cover as much ground as possible in related books in English to get an idea of the language being used. And if I came up against a term I really wasn’t sure how to approach, I’d turn to definitions (online or provided by the author) and Google Books and corpora websites. Nine times out of ten this would soon whittle down the possible translations enough that I could feel confident selecting one that fitted. Otherwise, it was doing more research, asking the author again for guidance, or just leaving it for now in the hope that another part of the book or some text I hit upon elsewhere provided an answer (and they tended to).

The funny thing is that’s very much my process for triangulating a voice for literary works. It’s all in the reading. Unless I can hear an English version in my head as I read the Chinese source text, which is a wondrous thing to have happen really but it does happen more often than you’d expect, then I look for “comp titles” that might give clues as to how the English should look/sound/feel. My attention when I find them, and when I review my own drafts, is on the narrator’s and characters’ word choices and also on the sentences—how they move, how they connect (or don’t), how they contribute to the storytelling with their shape and syntax as well as their content.

Fion: To wrap up, I’d love for you to share a few thoughts on what you’re excited about in the sinophone literary scene right now, whether that’s in translation or not!

Jack: I share a lot of what I’m excited about in translation from Chinese on the unfortunately named China Books Review. My column has been less frequent this year, but from now on it should be back to quarterly. On that site, you can also find great tips from the writer and translator Na Zhong for what people are reading in China right now. And if you want more insight into China’s literary scene, I recommend Andrew Rule’s Cold Window, on Substack.

It’s also a good idea to keep your eyes on Riverhead Books in the US, and Honford Star and Granta Magazine Editions in the UK. Between them there is plenty of great new writing from Chinese to come in the next twelve months. I include my translation of Xiaoyu Lu’s The Man Under Water in that (I’m manifesting). One upcoming book that’s particularly relevant to this interview, because of it’s themes and subject, is the Picun poet Xiao Hai’s memoir, which began as a short piece in Granta’s China issue last year.

As for what I’m excited about that hasn’t been translated yet, the list is long and the works are too varied to categorise in any meaningful way here. What gets translated and published in English is barely a drop in the ocean. But I’m hoping to find homes for some of them in the near future. And all I’ll say on that, for now, is: Goose!

-

Jack Hargreaves is a Chinese-to-English translator from Yorkshire. His translations, both literary and academic, have appeared in Asymptote, Words Without Borders, LitHub, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. Jack is one of the translators behind 李娟 Li Juan’s Winter Pasture and 柴静 Chai Jing’s Seeing. Most recently, his translation of 胡安焉 Hu Anyan’s I Deliver Parcels in Beijing was published by Astra House in October 2025.