On Translating Union in the Seventh Valley: A Ghazal of Sorrow

By Neshat Sadatmansoori

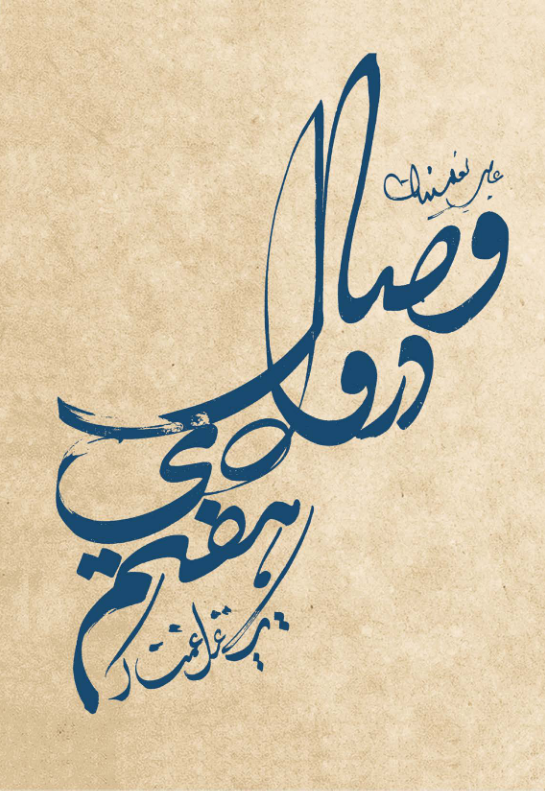

On the right: original Persian cover of Union in the Seventh Valley: A Ghazal of Sorrow by Abbas Na’lbandian. Designed by Reza Maafi.

On Translating Union in the Seventh Valley: A Ghazal of Sorrow

by Neshat Sadatmansoori

When I was a teenager, I used to go to my favorite bookstore in downtown Tehran after school classes ended. I would spend all my money buying books, eager to grow my young library. Of course, back then, I wasn’t aware that finding good books required more skill than reading them. I bought numerous books that turned out to be useless—ones I never opened, books with horrible translations, very expensive, or pretentious books, books that not even the dust settling on them adds anything to what I write.

After a while, I noticed that the bookseller had hidden some books on the shelves behind the ones she was selling. I wasn’t familiar with the expression “Offset Books” at that time—a phrase that might be unfamiliar to English-speaking readers. However, for Iranians, it evokes censorship and books that are officially unavailable through regular publishing channels, instead being printed and sold illegally. In Iran, these books are published in small, underground print shops that use offset printing technology.

After discovering these books, each time I visited the bookstore, I would stretch out my hand to touch the bottom of the bookshelves, hoping to find one of the “Offset Books.” First, I would touch them, pull one out, take it in my hand, and then buy it. Abbas Na’lbandian was one of the authors whose books I found among those offset editions. But who is Abbas Na’lbandian?

He was born in Tehran in 1947 and spent his summers helping his father at their small newspaper stand, where he spent most of his time reading. Despite being expelled and never finishing high school, he took up writing seriously. His first play with the long and strange title, A Deep, Big, and New Research about Fossils of the 25th Genealogy Period, or the 20th, or Any Other Period, There Is No Difference (1966), won several awards at the Shiraz Art Festival that year and made him famous. Later, in 1967, it premiered at the Iran-America Cultural Society Hall, directed by Arbi Avanesian. Na’lbandian published eight plays, three novels, and translated three plays during his short life, all published before the 1979 revolution in Iran.

While carrying elements of Sufism and the language of mysticism, Na’lbandian’s world leans heavily toward surrealism, absurdism, and existentialism. In every way possible, he sought to dismantle conventions from within. He achieved this through his uniquely long and often bizarre titles, the use of profanity, the depiction of intensely violent or sexual scenes, and the inclusion of complex, difficult-to-read words. His approach to rebellion against any authority within language extends even to how he structured his books and utilized the Persian script—misspelling.

It is important to note that Na’lbandian was, first and foremost, a playwright, and that his deliberate misspellings in his plays can be read as a rebellion against the very structure of playwriting—an insistence that the text is not written solely for performance, but also to be read. Na’lbandian creates a distinct vocabulary for each project and sometimes intentionally uses misspellings, repeating them so often that the reader begins to accept the wrong form as a new word, and, over time, this habit of misspelling has become almost a cultural signpost.

A while ago, someone randomly retweeted a photo on Twitter of a small roadside kebab shop somewhere between two cities in Iran. On its sign, the shop advertised “hot soup and ash” (a kind of Persian stew)—but both words were misspelled. The person who retweeted it wrote: “If Na’lbandian owned a kebab shop.”

I laughed so hard—and found it fascinating. That’s when I realized most people actually remember Na’lbandian precisely for his deliberate spelling errors, and how deeply that tendency has seeped into the Persian-speaking collective unconscious. So, this absolutely has to be taken into account in translation—and it’s one of the major challenges of translating his work.

What fascinates me most about Na’lbandian’s works is how, despite his deeply experimental approach to literature, they still provide profound insight into the political conditions of his time. This insight is conveyed not only through the atmosphere of his narratives but also through his skillful use of literary traditions. In fact, Na’lbandian both cares for these traditions and, whenever possible, abuses and stretches their boundaries. These traditions include the philosophy and literature of Suhrawardi, a foundational figure of Illuminationist thought; the mystical writings of Attar, the great Sufi poet of the 12th century; the work of Sadegh Hedayat, the father of modern Iranian storytelling; and even, perhaps, the works of Western writers such as Samuel Beckett.

Despite his early recognition, Iranian intellectuals never embraced Na’lbandian’s literary world in the way he truly deserved. This was mainly because he showed little interest in the social realism movement in art, which marked the decline of the Shah’s regime and was the prevailing trend among the poets, writers, and celebrated artists of the time. Na’lbandian was arrested both before and after the 1979 revolution; following the revolution, he was detained for four months. After his release, he lost his job and, at the age of forty-two, in loneliness and depression, he took his own life.

Neshat’s work was supported by an Emerging Translator Mentorship from the American Literary Translators Association. Read more at www.literarytranslators.org.

-

Neshat Sadatmansoori is an Iranian writer, translator, and interdisciplinary artist currently pursuing a PhD in Creative Writing at the University of Denver. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, where she was named the Anne Waldman Fellow. She was recently published in Bombay Gin and will appear in an upcoming issue of Sinister Wisdom. She is also the recipient of the 2025 ALTA Emerging Translator Mentorship.