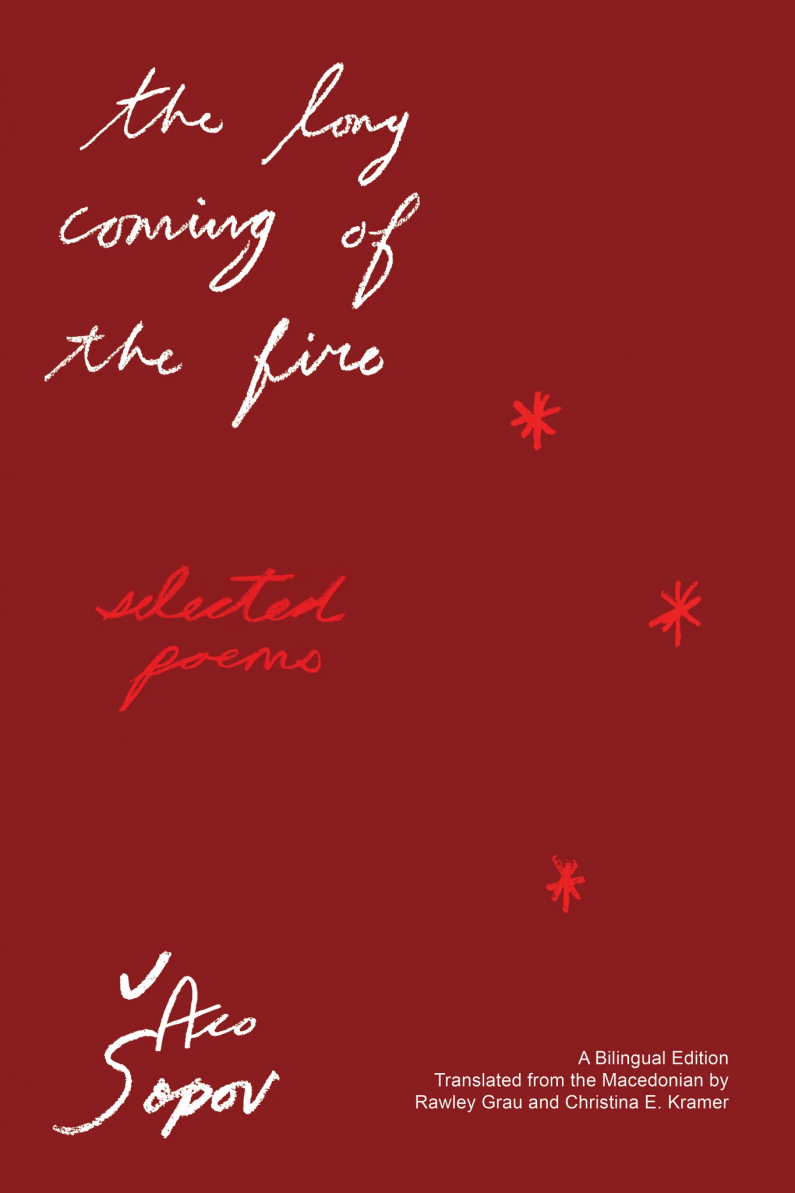

Review: The Long Coming of Fire

The Long Coming of Fire: Selected Poems

By Aco Šopov

Translated from the Macedonian by Rawley Grau and Christina E. Kramer

Deep Vellum Press, 254 pp., $17.95 (paper)

Review by Denis Ferhatović

It is a commonplace to reflect on the relative paucity of translated literature in the English-speaking word. This observation rings even more true when the works come from a language with a relatively small number of speakers, when those works were originally written in verse, and when they date from more than a few decades ago. Thanks to the efforts of Christina E. Kramer – one of the foremost South Slavicists in the West, and co-translator of the book under review – Anglophone readers have been able to access a number of current Macedonian-language novels, by authors such as Luan Starova (1941-2022), Lidija Dimkovska (b. 1971), Goce Smilevski (b. 1975), and Petar Andonovski (b. 1987). But poetry from North Macedonia has been much less represented, particularly in carefully prepared, affordable editions from a major independent publisher. This is why, from the very beginning, I must commend Deep Vellum Press and Kramer, along with her co-translator, Rawley Grau, and the compiler, the poet’s daughter and executor Jasmina Šopova, for their selection and presentation of poetry of Aco Šopov (1923-1982) in this bilingual volume.

In The Long Coming of Fire, Grau and Kramer craft a translation that blends a great deal of poetic inspiration with philological rigor. Neither of them is primarily a poet; they are both scholars of Slavic languages and literatures. (While Grau works with Russian and Slovene – the latter a South Slavic language like Macedonian – he has added Macedonian to his repertoire in recent years.) But the poems read like poetry in English. Where they do not—and cannot—reproduce every formal aspect of Šopov’s Macedonian, the translators turn to analogous devices available in contemporary English-language poetics. For instance, instead of full rhymes, they use oblique rhymes, assonance, and alliteration. Furthermore, they succeed at capturing the range of Šopov’s expression, from his elemental turbulent visions of the soul to vulnerable eroticism, from nature-documentary-style close-ups to tender care for a child. Let me provide a few, minimally annotated examples.

Ти знаеш – на ова место нема никаква трага

ни хишник овде ни ѕвер некаков мине.

Биди милозлива, биди дарежлива и блага

со ова тело од чекање што гине.

(“Седма молитва на мое тело”)

You know that there are no tracks in this place,

no predator is here, no wild beast passes by.

Be merciful, be generous and gentle with this body,

which in its waiting is wasting away.

(“Seventh Prayer of My Body”)

The ABAB rhyme does not survive the transfer, but there is oblique rhyme in by and away, and added alliterations on g and w enrich the texture of the English version.

*

Темниот удар на крилото

темно ја сече модрината.

Блеснува на студенилото

рибата в клунот раскината.

(“Лов на езеро”)

The dark beat of the wings

darkly cleaves the blue.

In the bill the slashed fish

flashes in the cold.

(“Hunt on the Lake”)

The sh- from slashed and f- and -sh from fish reunite across the enjambment in flashes, releasing intense poetic energy. While in the original, the word order is different (“Flashes in the cold/ The fish in the bill slashed”), the rearrangement by the translators creates a more powerful immediacy in English.

*

Таа ноќ е, сине, коњче што се спрема

да замине на пат неброени дни.

Сега сè е мирно. Сега ништо нема.

Смири се и ти.

Спи.

(“Залажување”)

The night, my son, is a horse getting ready

to leave on a journey long and steep.

Now all is calm. Now there is nothing.

You, too, settle down.

Sleep.

(“Trickery”)

Grau and Kramer render the second line of the stanza (word-for-word: “to leave on [a] journey [for] countless days”) “to leave on a journey long and steep” to gain the end rhyme with the last word in the poem, “sleep.” The echoing of steep and sleep reveals a certain menace in a text easily identified as a lullaby, the sensation also clear in the title. The Macedonian features the diminutive коњче, “horsey,” adding to the sense of disproportion between the single short night and the countless days in which it will repeat itself (before it takes over a person’s life, if imagined as a premotion of death to come for all of us). Horsey, as appropriate as it is in a poem nominally addressed to a child, might have introduced a discordant note in the formal literary English. Macedonian generally allows for a wider use of diminutives.

At times, the translators manage not only to rhyme, but to locate this rhyme on the same words as in the Macedonian. In “Third Prayer of My Body,” the end rhyme in “во коj со тишина се лечи/ телото мое молитвено што клечи,” turns into the internal rhyme, “where/ silence heals my body, as it kneels in prayer.” “[З]а смела последна реч/…/ остра како меч” smoothly transforms into “its brave last words/…/ sharp as a sword” in “Non-Being.” Convergences are part and parcel of any act of translation as much as divergences. Because of the distant kinship of the languages, some words present in both the original and the English rendition have both similar form and the same meaning, likely a consequence of identical Indo-European roots. “[М]оќно име,” that is, “mighty name” is an example of one such ancient correspondence in “Third Prayer of My Body.” Another is the adjective мрачни in “Non-Being” which Grau and Kramer render with its etymological cousin “murky” rather than “dark.” Most powerfully, these historical linguistic echoes can emerge in an entire line, as in “The Lake by the Monastery”: “Врсници сме, водо, од два света двојници,” “We’re the same age, water – from two worlds, twins,” where, further, the syntax in the English closely follows the original, and the auditory play on v (водо, два, света, двојници) is recreated with w (water, two, worlds, twins) in the same words.

In other places, the inspired choice of elevated diction adds to the poetic quality of the translators’ work. “With silent throats the fish incant a vatic song” (“Tempest”) brings out the Miyazakian image in Šopov’s line “Најсудбоносно пеат рибите со неми грла” (word-for-word: “most fatefully sing the fish with mute throats”). The apocalyptic charge of “The Long Coming of the Fire” comes through in the alliterative pairing at the end of the English line “Stars will mix with beasts, toxins with tillage,” that translates “Ḱе се измешаат ѕвезди и ѕверови, отрови и ниви” (literally: “Stars and beasts, poisons and plowed fields, will mix”). Alliterating the first pairing, “stars and beasts,” the line begins with the voiced alveolar fricative /d͡z/ peculiar to Macedonian among modern standardized South Slavic varieties. The willingness to seek out stranger, more resonant words in English, even when the original is relatively plain, adds to the inspired texture of the work.

Grau and Kramer are conscious of the choices they had to make when English offers more than one equivalent for the Macedonian. Sometimes, they are able to offer two words for one: in the second line of “Scar,” they write “nine gorges, nine throats” for “девет грла” because it is important to show that грло has both the anatomical and geographical meaning, which of course chimes with Šopov’s conception of the human body’s primal link with the landscape. (Gorge indeed comes from the French word for “throat.”) But usually, the translators have to pick a single sense. In their introduction, “The Fire is Here: The Long Journey of Aco Šopov,” they speak of their decision to render песна as “song” rather than “poem,” which emphasizes the poet’s alliance with the ancient and folkloric oral utterance, but obscures any metatextual references to the written form. Other examples include игра consistently translated as “dance” (rather than “play” or “game”) in several poems, and час as “hour” (rather than “moment”) in “Non-Being.”

A more marked loss that results from the linguistic difference happens in “Eyes,” a canonical poem about the experience of the War of National Liberation (Народноослободителна војна, 1941-1945). The fatally wounded comrade is a woman, and the poet’s beloved, Vera Jociḱ, as we find out from the endnotes supplied by Grau and Kramer, and if we are careful, at the end of the fourth stanza of the English version, in the remark “you leapt like a tigress” (“ко тигрица рипна”). The Macedonian also indicates the feminine gender earlier, in two forms, the adjective збрана in the first line, and the address “о другарко” in the middle of the poem; the English modifiers, “gathered” and “dear comrade,” of course cannot communicate this fact on their own. On the other hand, the English here underlines even more than the original the closeness of love for the anti-fascist struggle, one’s country, comrades-in-arms, and a woman, inextricable parts of Šopov’s poetics in “Eyes” and elsewhere.

Without a doubt, The Long Coming of Fire is a considerable achievement. Grau and Kramer’s scrupulous, coruscating translation and meticulous paratexts offer an excellent entry point for English-speaking readers into the tormented, passionate, and surprising world of Aco Šopov’s poetic creation. Many preoccupations of the twentieth-century Macedonian poet have spilled over into our time: the shaping and deforming powers of Nature and the humankind; the ecstasies of the sensual body and its limitations; and the challenges of global solidarity (in Šopov’s case, along the East/South, Yugoslavia/Senegal axis) and self/Other envisioning (the Macedonian Slav poet’s voicing of a Macedonian Romani master of bricolage in “Rag-and-Bone Man”). We can now, bilingually, dwell in the volcanoes and burnt-out stars of the poet’s voice, and see what erupts in us.

—

Denis Ferhatović is a Bosnian-American scholar and writer, working and playing with various languages both medieval and modern. His essays, poems, reviews, translations, and co-translations have been published in Rumba under Fire, Index on Censorship, The Riddle Ages, Iberian Connections, Turkoslavia, Trinity Journal of Literary Translation (JoLT), DoubleSpeak, and Asymptote. His scholarly work appears in various journals and essay collections. His monograph Borrowed Objects and the Art of Poetry: Spolia in Old English Verse (2019) recently came out in paperback.