Review: The Brothers Seven

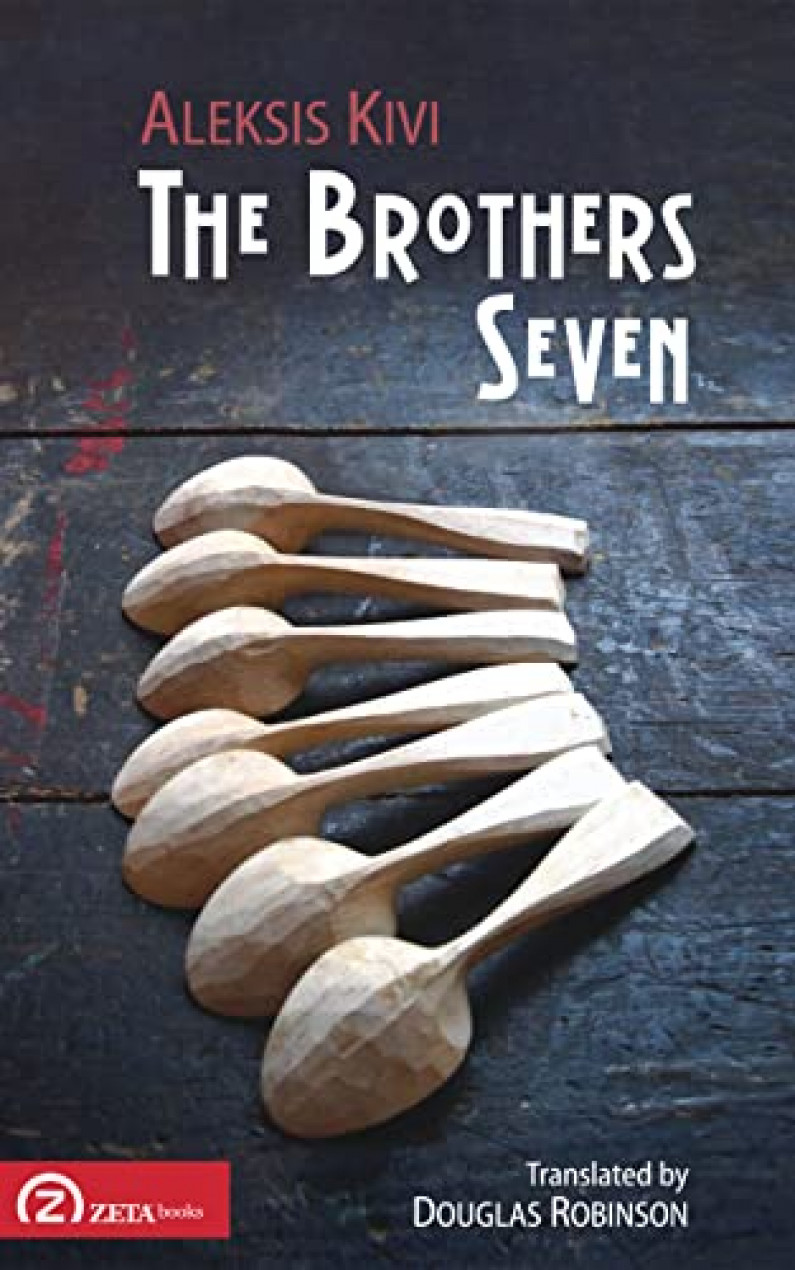

The Brothers Seven by Alexsis Kivi

Translated from the Finnish by Douglas Robinson

Zeta Books, 462 pp., €25.00 (paper)

Review by David M. Smith

Given its prominence in the literature of its home country, one is tempted to call Aleksis Kivi’s The Brothers Seven (1870) the Great Finnish Novel. But to call it such is almost to tame its reckless energy, for it explodes the conventions we normally associate with novels. For one thing, this tale of the seven titular figures—Juhani, Tuomas, Aapo, Simeoni, Timo, Lauri, and Eero—conveys speech directly, in the form of a drama, with action indicated by stage directions. It is almost as if too much 3rd-person narration would get in the way, as the brothers stumble and claw their way to respectable adulthood, struggling to reconcile their impulses to the orderly demands of civilization.

It is the book’s sprawling, unruly energy that Douglas Robinson endeavors to harness in his translation. His is the third into English, after Alex. Matson’s in 1929 and Richard Impola’s in 1991. What distinguishes Robinson’s approach is his thoroughgoing use of an archaic, quasi-Shakespearean English, which he justifies in part on the grounds that Kivi was well versed in Shakespeare. But Robinson does not deploy archaisms for the sake of elegance or refinement. Quite the contrary: the archaic English of Robinson’s Brothers Seven is deliberately rude, profane. It gleefully throws its weight around, more a boisterous Falstaff than the hushed solemnity of the King James Bible. As Robinson explains in his preface:

I have translated it so as to celebrate and heighten what I above called “the novel's grotesque, carnivalistic exuberance”—pushing that exuberance and verbal energy to extremes that often overflow the bounds of translational best practices and good taste. Kivi is a bold, cast-caution-to-the-winds kind of writer, and demands the same boldness of his translator. My only hope of capturing most of Kivi's explosively transgressive brilliance is to transgress as explosively as I am able.

Thus, for instance, Robinson’s translation is characterized by the extensive use of alliteration: “… sweeping thro the waist of that dark whiskery weald, rasping and razing, scratting and scraping, and the spruce boom'd and throbb'd and bow'd deep.” Where there exists no precise English equivalent for a Finnish word, Robinson can be bold enough to invent a neologism, like “gambag” for a particular kind of sack that is unknown outside of Finland’s borders. Nor is Robinson afraid to use anachronisms, like an allusion to a 20th-century Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, in this translation of a 19th-century novel. Rather than letting this choice and many others like it pass in silence, he explains it all in nearly 90 pages of endnotes and a glossary of the early modern English he uses.

As entertaining as the novel is, therefore, a casual beach read it most certainly is not. In his preface, Robinson insists that the difficulty of the original requires a corresponding resistance in the translation: “Kivi’s language…is difficult even for scholars of Finnish literature. It must be studied to be fully appreciated.” In the translation, this plays out in sentences like: “Who jigg’d the shanty that we while-ere had to hear with our hackles up?” While such obscurities are sometimes made clear by the surrounding context, many others require a trip to the glossary. Some readers may well find this disruptive. Other readers may—as I did—acquire a certain comfort in letting the obscure remain obscure, especially when doing so allows the text’s other qualities—its playfulness, its irrepressible, exuberant energy—to shine through.

Robinson is also a theorist of translation, and in his monograph, Aleksis Kivi and/as World Literature (2017), he critiques the two previous English translations of The Brothers Seven. To Robinson, the shortcomings of the Matson and Impola translations are symptomatic of the traditional self-effacement of the translator; to the extent the translator is a writer, she must always be a “worse” writer than the original author. The traditional formula demands that the original be placed above the translation; it is presumptuous when a translator crosses the dividing line, trying to match the same quality of writing as the original author. The art of translation must be secondary, derivative. On Robinson’s account, this is what causes Matson and Impola to hedge somewhat, and not take enough creative risk.

The question each reader may have to answer for herself is: How much risk is too much? Besides the abovementioned anachronisms, it can be occasionally disorienting to read, side by side with the quasi-Shakespearean phrases that seem lifted from a slangy American register, like “so what you’re saying is,” “what I don’t get is,” and so on. But this, too, presumably has its purpose. By means of its very unnaturalness, the text’s status as a translation gets emphasized. It never lulls us into thinking we are dealing with the thing itself, as if the translation were a transparent window that granted an unobstructed view of the original. On the whole, the strategy seems one of defamiliarization; by using techniques we normally do not associate with translation, Robinson puts the artifice on full display, making us aware as few others dare to do that what we are reading is the product of a translator’s choice. Not a completely arbitrary choice, mind you, but a choice nevertheless, among numerous possible choices. It is on those terms that this translation must be judged, and on those terms that, by and large, it succeeds.

—

David M. Smith is a translator of Norwegian fiction, including The Calf by Leif Høghaug, a forthcoming experimental translation into Southern US dialect from Fum d’Estampa Press. He has an MFA in Literary Translation from the University of Iowa. He can be followed at @smithigans_wake on the platform formerly known as Twitter.