Review: Soul House and The Cheapest France in Town

Books discussed in this review:

Soul House

By Mireille Gansel, translated from the French by Joan Seliger Sidney

World Poetry Books, 168 pp., $20.00 (paper)

The Cheapest France in Town

By Seo Jung Hak, translated from the Korean by Megan Sungyoon

World Poetry Books, 120 pp., $20.00 (paper)

Review by Stephen Meisel

The prose poem never fails to test our own definitions of poetry. As early as Baudelaire and Rimbaud, its effect has always been to blur lines between genres, tastes, and cultures. This is always the effect of hybrid forms–whether we’re talking about mockumentaries, lyric essays, or multi-media art installations. They can make us see things differently—even ourselves. The power of an unfamiliar experience can call our traditions and ingrained judgments into question.

What an artist does with this potential, though, is where the lightning strikes. Two titles from World Poetry Books, Mireille Gansel’s Soul House and Seo Jung Hak’s The Cheapest France in Town, introduce novel ways to let the current flow. The Cheapest France in Town slides onto the stage with a joke, a nod to poetry’s place in consumer culture:

The value of this book is, at present, the same as the lowest online exclusive price for a half box of thirty Shin instant noodles, though Shin would be slightly cheaper if you paid with a rewards card.

A careful comparison of prices before buying may be a great help to your life.

And right away, The Cheapest France in Town is off to the races, full of humor, space aliens whose planets are destroyed by an “ultraelectronicplanetaryprofessionaldestructive-formidableterrifyingantennalbeam,” and recipes for love that sound like a step-by-step for instant noodles. When its irony and wit let up, they’re often for moments of dystopia and ennui, with bureaucratic regimes and urban landscapes providing the backdrop, such as in the poem, “Dopamine,”:

When he opened his lunch he saw the word “freedom” written in black beans. His colleagues all groaned. Turned out he and his family were members of the rebel army. Right, we saw his underpants with words like “love” and “trust” stitched in the corner.

It’s rare we see a poet as occupied as Seo Jung Hak is with the low-down, the discarded, and the trivial: paper boxes and rewards cards, big red buttons and TV producers. In this world, poems are their own pathetic attempts at the high brow, drowned out in the noise of consumerism and everyday concern. We’re lucky, then, that Seo Jung Hak lets us in on the joke. After all, we’re reading a poetry collection that turns discount coupons, soap opera romances, and issues of Military Satellite Fans Monthly into something profound and delightful, where love, even in its most sentimental manifestations, is coupled with surreal imagery and pained absurdity, as in “Still, France”:

Laying in bed after checking it was raining out the window, troubling the black heavy curtain. Of course, the rain had been pouring incessantly for 13 years and turned off the light next to the bed. The room was entirely like an aquarium. The rippling shadows were dizzying.

To that point, translator Megan Sungyoon captures the fractured syntax, odd punctuation, and puns of Seo Jung Hak’s poems with such skill that all of these elements carry over into the first English translation of his work. The Cheapest France in Town only the second collection that Seo Jung Hak has published over the course of 18 years. Let’s hope we see more in the next twenty. Either way, “the same and tomorrow night garbage [is] going to be cleaned up.

Where Seo Jung Hak uses humor and dissociation, the poems in Mireille Gansel’s Soul House, with their focus on history, memory, and migration, penetrate with sharpness and intensity. Her pieces pivot between complete sentences and fragments, with occasional punctuation. This style evokes how memory feels: variable tempos and overlapping ideas. Her French is conversational but not quite casual, and perhaps the biggest challenge here for translator Joan Seliger Sydney is capturing its unique pacing and measured tone, which both play off of French syntax and diction. What’s more, Sydney also preserves the multilingualism of poems that dip into meditations on German words or phrases or use unique French terms like maquisard. This is a vital choice in a collection so concerned with the potency of translation.

At its core, Gansel’s collection is rooted in an ethereal clash between cultural specificity and those universal experiences of childhood and home, where our love of the meaningful and the beautiful can provide a refuge to renew our strength against violence and cruelty. It’s no surprise that Gansel is a seasoned translator herself. Soul House is full of investigations into what is lost in between the cracks of history and time, of how much our souls can carry over across languages and generations. Gansel’s own childhood, which she has written about in her long essay “Translation as Transhumance,” is not a boundary that separates her from other writers, but the foundation for an artistic practice that crosses borders. The Budapest of her childhood moves beyond a particular place at a particular time, full of “intonations of Hungarian mixtures over there on the side of the Danube you will have learned for life.” It becomes a jumping-off point into “a country of silence.”

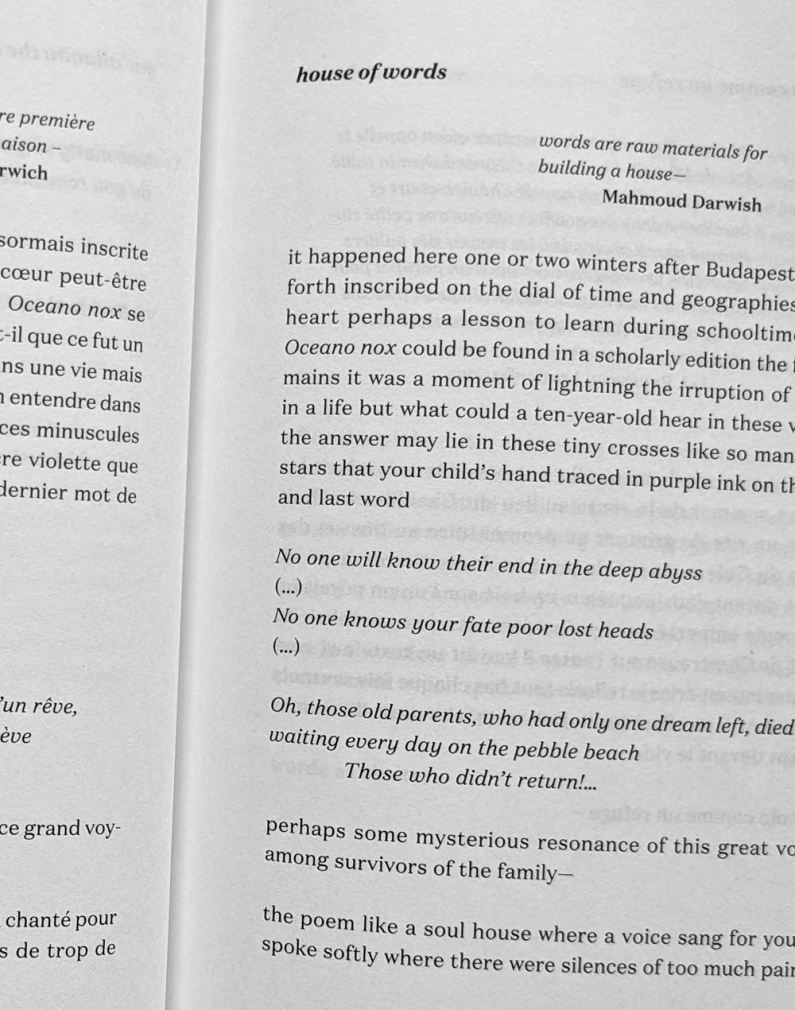

In this country of silence, a house that all people living and dead can inhabit, Ganselle conjures silhouettes of figures both monumental and forgotten–on a scale spanning several decades and multiple continents. Quotes from Mahmoud Darwish and Anna Akhmatova are just as likely as accounts of Austrian museum visits and English puffin migrations. Broader discussion about translation blends with blurred remembrances, both personal and retold. All of it provides the source material for Gansel’s concerns over the point of beauty and role of language, for which her poetry is a loyal and constant conduit. The metaphor that extends throughout the book is a comparison between poetry and architecture. It begins with the first poem, “to inhabit beauty”:

beauty is a house one inhabits perhaps the first one perhaps the only one–

against all odds

Gansel returns to this idea in “the meeting point”:

I understood that hospitality is to become at our turn your hosts and suddenly in the full noon sun there was this space to say with your own words your roads of exile your words like a shared house–

One of the more indicative moments in the collection gives even further definition to this idea. In the poem “leave no trace,” Ganselle reads Walter Benjamin’s Pariser Passagen in London, where she discovers the word Gehäuse, which Benjamin defines as ‘“where one takes shelter. Finds refuge.’” It’s a quiet moment in a book whose empathy and heart stretch across long distances and over so much catastrophe, but it perfectly captures this collection’s core: language and translation as forces that allow us all to find safety and refuge. It’s true, then, that Gansel’s lyrical pieces make for great shelters.

Soul House and The Cheapest France in Town sit at opposite ends of the emotional spectrum. In both books, though, you’ll find distinguished writers who captivate and challenge with a poise as light as air. The Cheapest France in Town succeeds triumphantly as a curious, ironic blend of unchecked consumption, malaise, and the absurd. Soul House, with its faith in intellectuals and artists, “to inhabit beauty against all odds,” provides a prime example of this beauty in action. Joan Seliger Sidney and Megan Sungyoon have done Anglophone readers a great service by introducing us to two poets of distinct and thrilling voices.

—

Stephen Meisel is a writer living in Atlanta, GA. His fiction and reviews have appeared in X-R-A-Y, Southern Review of Books, and Heavy Feather Review. He can be reached at meiselstephen@gmail.com