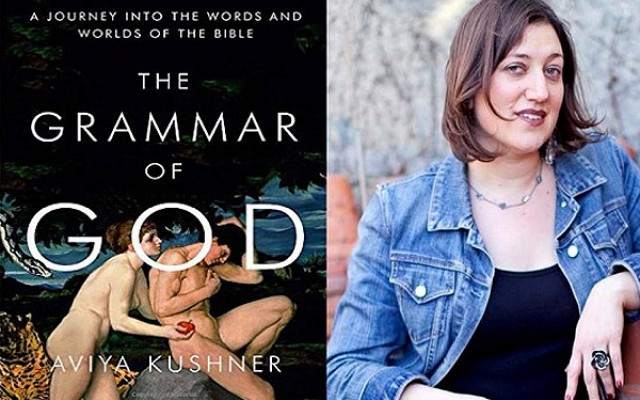

Review: The Aunt Who Wouldn't Die

The Aunt Who Wouldn't Die

By Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, translated from the Bengali by Arunava Sinha

Harper Collins, 160 pp., $15.99 (paper)

Review by Vandana Nair

Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay has always possessed a spontaneous, comic bent: in both his adult and children’s fiction, he has captured the absurd and the weird that exists within conventionally-patrilocal Indian joint family structures, and how these corral women together into an uneasy sisterhood. In a masterstroke of inventiveness, he questions these oppressive traditions against women through the vitriolic voice of a ghost.

Mukhopadhyay’s The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die, skillfully translated by Arunava Sinha, weaves a multi-generational tale of an aristocratic, indolent Bengali family, who would rather sell their land and survive off the profits than work for a living. Sensibility prevails in the form of Somlata, the 18-year-old daughter-in-law of the family, to gently coerce her 36-year-old husband to step down from his high horse and open a shop to sell sarees. Pishima, the ghost of her husband’s dead aunt, who deviously leaves her gold with Somlata after she dies, aids her in this rescue mission. Each time Somlata finds herself in a deadlock, Pishima appears in a flash of white at the most unsuspecting corners of the decaying Mitra mansion, to goad her uneasy collaborator into performing drastic deeds that defy traditional family conventions. Even though she fears this ghost, who alternately curses her, threatening a stillbirth, or provokes her with salacious talks of conjugal lovemaking, Somlata manages to find the strength to safeguard Pishima’s gold and pull her family out of poverty. In Pishima’s bitter tirade to reclaim her ancient, heavy ornaments, Somlata and the reader get flashes of morbid sadness that the old widow experiences, knowing she was loved only for her hundred bhoris of gold.

For all the venom she spews, the ghost of Pishima is what drives this book: she is impossibly, wickedly profane. The semiotics of Pishima’s name, Rashomoyee, are almost Dante-esque—a subtle parallel could be drawn to The Divine Comedy where Sapia, the idiot in Purgatory punished for reveling in the suffering of her neighbors, points out that “Although my name is Sapia, I was anything but Sapient.” When Somlata in conversation with Boshon refers to Pishima as Rashomoyee, her given name, its subtle irony is not lost on a reader acquainted with Bengali text and culture, for it refers to someone brimming with aesthetic pleasures. As a child bride widowed at 12, Pishima’s life has been stripped of all aesthetics, for she has spent the better part of her long, lonely life shrouded in a white saree, a permanently shorn head, ingesting flavorless, ascetic food, and in her own words “burning” for pleasures of the flesh, until Somlata stumbles upon her dead, unsated, seventy-year-old, inert form.

In the translator Arunava Sinha’s words, “the greatest challenge in The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die was to find a voice in English for the ghost of Pishima, the dead aunt.” To keep the intention of the original Bengali text in English—a tongue that prefers sparer language and stage—could have resulted in a severe digression from the character of Pishima in her ghost form, especially considering the many expletives that fall from her mouth like leaves in autumn. Even though the translator knows that an elderly woman character within the setting of a vintage Bengali family, would probably never speak in formal English—a language that was perceived as the power language of the colonizers—let alone use it for imparting double entendres, his discomfort does not show in his prose. To Sinha’s credit, he has transcreated a vengeful ghost, which alludes to all earthly pleasures she has been deprived of in life, and even her voyeuristic satisfaction in asking for details of Somlata’s sexual life invokes a tragicomic absurdity rather than offend feminine sensibility.

“Ish, what a shrinking violet. Is it a crime to ask? Married at seven, widowed at twelve. I wasn’t even old enough to understand. By the time my body woke up, my hair had been cropped, and I was reduced to one meal of rice a day and fasting on Ekadoshi. How will you understand what I went through? Tell me what it’s like?

“It’s good.”

“Damn you, you bitch. Everyone knows it’s good. Give me details.”

Sinha purposefully retains the original Bengali words for the names of festivals, foods, of relationships that exist within the family to create an intimate, hetero-patriarchal world that Pishima, Somlata and generations of women live and breathe in. The rhythm of their tongues defines those morning-to-night chores and flavors they crave, the fraught unions they learn to be confined within, and the multiple relationships they navigate around until death liberates them.

In death, Pishima is pure theatre, and the plot moves forward because of her profane, ghostly agency. She is more alive and free in her afterlife form than she was as the ranting, de-facto head of the family in her aristocratic three-large-room domain. While Somlata holds—her mild, piteous mother-in-law, her shrewish, harridan of a sister-in-law, her much older husband and various family members—in cow-like deference, it is the ghost of Pishima who follows Somlata, the young daughter-in-law burdened by her own niceness and clues her into the foolish, feckless and adulterous behavior of the men in the family.

Men in this novella are like supine, black-and-white chessboards—chequered pastimes and prostrate inheritors of sexist family structures—where they call the rules of the game from their dormant state. Mukhopadhyay is interested only in the women, who move like pieces on the board as they become conspirators and enemies, spectators and silent protesters, homemakers and sleeping partners in trade and life. Somlata is meek but cleverly urges her husband to trade in sarees. Her Jaa, her sister-in-law, wants to pounce and grab the family gold, but is punished by Pishima’s ghost for her greediness until she finally embraces Somlata’s company because of their mutual love for Boshon. And young, progressive Boshon, who wishes to wander “off to valleys, the mountains, the rivers, singing with her hair flowing.” Somewhere, Mukhopadhyay’s writing suggests that too often, men are held in power and blame in Indian family structures; however, feminism is often hard-won because women forget to acknowledge each other’s mischief, or dreaminess, or irreverence, instead expecting only a chronic niceness from their own sex, and to come together for a common cause despite being complex individuals.

Because he wants women to look at women in discrete ways, Mukhopadhyay braids his narrative through two points of view of significantly dissimilar women—Somlata, the proverbial, god-fearing, suitable daughter-in-law from a poor family, and Boshon, her pampered, modern, privileged daughter who has feminist leanings. Boshon’s point of view, when it begins, appears as mysteriously as Pishima’s ghost, and the reader has the feeling of escaping into a new, natural world of romantic experiences in stark contrast to Somlata’s materialistic old world of hardships, hidden gold bhoris and repressed female desire. Perhaps it is this paradox—these co-existing antitheses—that makes this story more than a ghost story, and is what prompted Arunava Sinha to select this fiction of perfect length and pace for translation, knowing his penchant for stories in which “there is inevitable seeking of what is not, what probably cannot be.” What Mukhopadhya is seeking comes together in Boshon’s candid contemplation, “How fortunate I wasn’t born in that time! My god, what a horrible system. No wonder women are rebelling for freedom,” along with relieved perception that Pishima’s ghost has finally come to rest. A ghost-like white space of an ending puts young Boshon at the brink of infinite possibilities with familial relationships that have endured through tough times and a mellower social structure and norms.

In images of Boshon occupying Pishima’s three enormous rooms all by herself, pushing a broken-down lorry while returning from a picnic with friends, and moving about town on her brand-new scooter, the phantom of a post-aristocracy utopia is slowly climbing the steps. Long-held gold and grudges are put aside when Somlata and her sister-in-law—two women of a timeworn generation—come together in uneasy camaraderie to gift the forthcoming generation of girls what they value most: independence and selfhood.

_

Vandana Nair grew up in India, believing that relationships need to be nurtured from their roots. Living away from her birth country has given her the essential distance to mine stories from her cultural home and heritage. Her debut novel is Punch, and she has contributed a short story, The Signature, to The Knot Wound Round Your Finger (Bell Press), an anthology on memory, history and inheritance, which the publishers nominated for a 2021 Pushcart Prize. https://twitter.com/nairvands