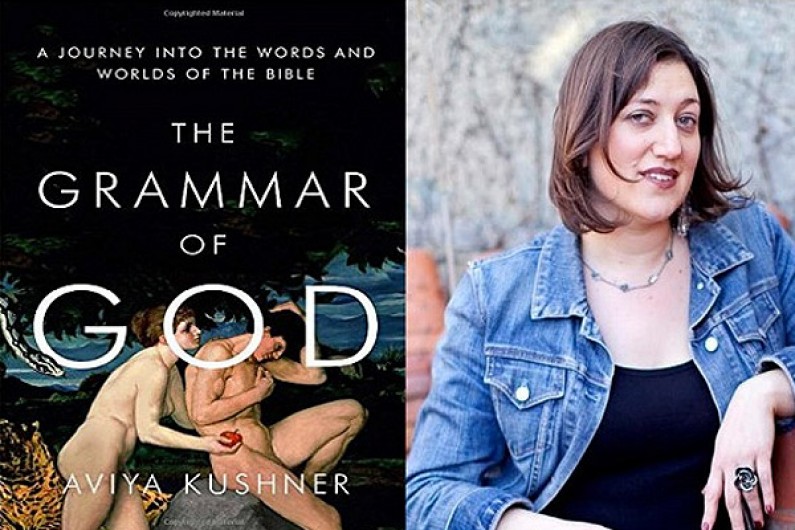

In Conversation: Aviya Kushner, Author of The Grammar of God

Aviya Kushner cares a lot about names. In her visit to the Translation Workshop to discuss her book, The Grammar of God, she expressed unease with English’s inability to comport both name and story in the Bible. “Adam,” for example, doesn’t just refer to Adam, specifically: In Hebrew, “Adam” means “man.” Same for Eve, who in the Hebrew Bible is “Chava,” meaning “life.”

But names are just one part of the Hebrew Bible that is unknown to English speakers in its various Old Testament translations—from King James to NIV. The Grammar of God, released this September through Spiegel and Grau, is an attempt to personally reckon with the Hebrew Bible’s long and storied tradition of syntactical ambiguity, scholarship, and discussion. While English speakers believe to reliably understand the prose of the Old Testament, the Hebrew Bible’s readers are well aware of the powerful ambiguation at work in the text, which has allowed for scores of Biblical commentators to discuss its multiplicities, its meanings, and possibilities—all the while embracing the powerful hermeneutic fallibility within a sacred text.

Kushner reveals the labyrinthine corpus of Hebrew grammar to the Anglo reader, using personal narrative to guide us to a more resonant understanding of what’s at stake in the Hebrew holy text, and what is all-too-lightly forgotten in its perilous journey into English.

We exchanged questions with Kushner, after reading her book (and loving it).

—Patricia Hartland

You describe how, at one point years into the project, you found your “own physical and mental energy waning,” which drove you to question your need to continue. As this realm of doubt can be pervasive for writers/translators, what might you say to someone entering that space?

I would say that doubt feels terrible but is actually a good thing. It’s so hard to feel it at the time, during all the challenges of writing and editing, but I believe that many great books come from some sort of war the writer or translator has with himself or herself. It’s important to question the entire project, and to do it often. Auden had it right when he said that from the arguments with others we make rhetoric, but from the arguments with ourselves we make poetry.

What is the reader’s responsibility toward works of translation? Should a reader hold all (literary) translations as hermeneutically accountable as Biblical translations?

What an interesting question. I think the reader of translation’s main responsibility is to acknowledge that it is a translation. This means knowing who the translator is, and reading the translator’s preface if there is one. The reader might also acknowledge that part of what he or she loves or hates is the translator’s work, not the writer’s.

In the beginning of this project, I was often disturbed by translations, but as the years rolled on I found myself appreciating all kinds of translations and approaches, andthinking deeply about the great sacrifice of time translators made to bring the Bible to us.

In Walter Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator,” Benjamin concludes that the ideal translation is interlinear—how would you respond to this assumption? What kinds of translations would like to see more of? How might English-language readers and writers accommodate a new sensibility to reading translations, if at all?

I often find myself agreeing with Benjamin, and re-reading his work. But Benjamin is about ideals, and not necessarily reality.

In reality, I think technology offers some exciting possibilities for translation publishing. I would like to see more translation publishers include the original side-by-side with the text, even if it’s only for a few pages. It’s important for readers to see if, say, a stanza has been added or eliminated—as Robert Lowell freely admits that he did in his introduction to Imitations.

Presentation is so important, and I think the look of a book really matters. With a translation from a country, language, or literature the English-language reader may know nothing about, engaging introductory material can be critical. Who is the writer, and why does he or she matter?

I really love it when a translator is clearly involved in the appearance and arrangement of the book. For example, I thought Peter Constantine’s translator’s preface in his Collected Babel was so helpful, and I liked the folio of prefaces that were presented—one by Cynthia Ozick and one by Nathalie Babel. I also appreciate it when the translator flags a major translation issue for the reader. I recently read a novel translated from the Spanish that hinged on a word that seemed awkward in English. It turns out that it was a made-up word in Spanish; I was really happy that the translator chose to share that with the reader, and explain her solution.

In your chapter titled “Memory,” you write “the past is already buried under a Sbarro restaurant. Even the destruction of European Jewry can be hidden by the same stores that homogenise stories all over the world.” How can (specifically English-language) translation avoid this kind of domination (if possible at all)?

I think translation is an important weapon in the battle against homogenization. If you are reading about what’s happening in Norway, or Afghanistan, or Chile, you are helping to preserve narratives. Translators can also help by including notes that note important points for readers; adding context can help make sure we keep history alive.

At the same time, I do think language study is so important, and the danger of having many translations into English readily available is that the need to learn a language may be diminished. But of course, no one can master every language on earth, so we will always need translations to get a fuller understanding of the world.

Given its long hiatus as a spoken language—and its relatively recent re-emergence—has modern usage of Hebrew at all been informed by historical translations and understandings of the language and the Bible?

The Bible is very much a part of modern Hebrew, and many contemporary Hebrew words are actually ancient words or variants of them. The Bible’s presence in contemporary Hebrew is a big part of what makes the language so beautiful and so incredibly attractive to writers, who get to work with ancient resonances all the time.

You write: “The reader’s task is to ask what is going on. No matter how many readers have read before him, the reader must read again, must investigate, must lift the veil to seek the face of the text, over and over again.” What might you imagine will occur to your text at the hands of your readers? What might emerge or form?

I hope readers will stop and think about the fact that the Bible is often read in translation, and to consider what that means and how it has affected history. I hope readers ask—what is translation, exactly, and why does it matter? And how does translation affect how I understand the Bible?

The Bible is always controversial, and every line is a minefield. I expect that readers will have many different reactions to The Grammar of God. My hope is to start a conversation about how we read.

I have no idea where it will lead, but I do hope people will start talking about the Bible and translation and how language shapes what we believe.

You insist your work is not scholarly, and yet, reading it, we are impressed by your thoroughness, knowledge, scope, and rigor with regard to Biblical translation (and re-translation). Why is it important to account for your personal intervention, and what led you to writing your book this way? How might we—as readers—respond differently to a text that feigns objectivity and authority?

I worked hard to delve deeply into the text and make things as clear and beautiful as I could possibly make them, but with the Bible, there are always more angles to consider, and there is always, always, more to say. I did not try to write an exhaustive book, as a scholar may have.

I was amazed to hear the Bible being discussed as if it was just a read text and not a lived text. I wanted to show the conversation around the Bible, and how those arguments and discussions have gone on for centuries. I wanted to show how the Bible is alive in homes like the one I grew up in. To do that, I felt I had to write about people, and to find a way to combine the personal and the Biblical.

So I wrote about the surprises of encountering the Bible in English after a lifetime of reading it in Hebrew, but I also very much wanted to convey how the Hebrew Bible is alive—how it is talked about.

Unlike followers of the English-language Christian Bible, which claims to be authoritative and silent, commentators and readers of the Hebrew Bible thrive on ambiguities. Why might we embrace—rather than deny or stifle—the fallibility and instability inherent in all aspects of language and translation, and what might this acceptance look like?

I think it’s interesting to consider the most obvious of points—that translators are human. Translators often have to make judgment calls, and when we read translations, we are reading those judgment calls—wise and unwise, learned and ignorant, intentional and mistaken. The same is true for commentators, who are of course human as well.

There are so many ways to understand a text, and I think considering various points of view and trying to comprehend where they came from can be a very enriching experience, a feeling that the world itself is widening.

This does not mean we should ignore errors. We should discuss the difference between a mistake—say, a misreading of a noun as a verb—and a difference in understanding a scene. But overall, rather than being afraid of different readings, I think we should at the very least familiarize ourselves with them and with the thought patterns that created them.

Argument and discussion keep books alive. I truly believe that the Bible is with us today because so many readers fought over it. It’s a marvelous thing, to disagree, and to feel so passionately about a text. It continues to amaze me how many people, throughout history, were willing to give their lives to keep this particular book alive. Some of those people were scholars, some were rabbis or priests, some were ordinary folks, and some were of course translators—but they were all passionate about their task. Those passionate readers are the reason the Bible is still with us.