From the Sketchpad: Translating Billy Collins

For me, translation has been a journey of unexpected discovery. It was never something I intended to do, but a dear friend suggested that we co-translate a book of poems. On one of the last pages I wrote a couple of lines thanking him for showing me the generosity of the line, in reference to the narrative and lyrical power that prose poems can deliver.

So, there we were with Sharon Olds’ The Dead and the Living (1983) in our hands, not sure how to go about it. An odd ensemble of sorts. My friend Carlos had successfully translated W.B. Yeats and Browning into Spanish, while I had never even attempted a Tylenol label. With no work strategy, we just sat down, met to compare our versions poem by poem, until we reached some semblance of agreement; lots of case-building for our word choices—tone, phrasing, metaphor equivalences—down to the deepest etymological roots.

Browsing through bookshelves in a summer visit to NYC, I came upon the poetry of Billy Collins. I was completing a Masters in US contemporary poetry at the time. The literature of the field connects his poetic dictum to pivotal figures like Whitman, W.C. Williams, and Wallace Stevens. A democratic and domestic approach to the idiomatic rhythms of the lyrical American man. I spoke with my publisher about Collins and his reputation in the US. Praise for my Sharon Olds’ translation in a national Spanish newspaper green-lighted the project.

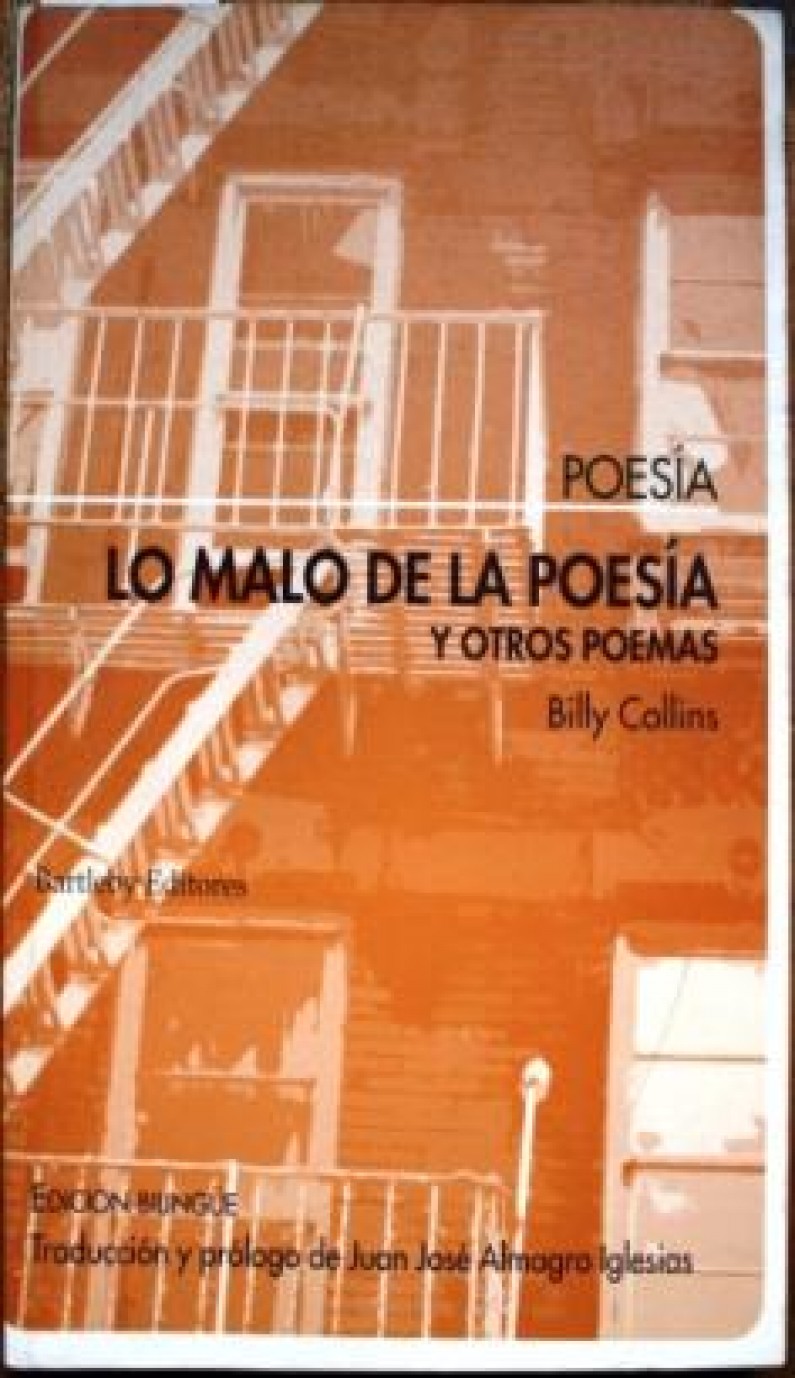

The book that I chose to translate was The Trouble with Poetry (2005). This time I was more aware of what it meant to approach somebody’s poetry, to make decisions about literality, metaphorical constructs. Some shared, some cultural, some writer-specific. Perhaps this project also gave me a sense, an understanding of my own creating process; the stages, the world it was morphing into … what it meant to write.

Reviews came out: “The translation is vivid, impeccable.” Wow, who, me? Without connections? This guy from Madrid? Kind of nice receiving texts from publisher, poets, family and friends who read the newspaper article. From this moment I followed Billy Collins’s work, watched his TED talks, TV and radio interviews, etc. Strangely enough, I no longer had a desire to translate.

I leafed through my translations of Olds and Collins into Spanish for this blog entry, and I noticed how important poem titles are, to get them right. Even if in Spanish they’d expand syllabically: “Fool Me Good” became “Engáñame sin que me entere”; “On Not Finding You Home” transformed into “Acerca del hecho de no encontrarte en casas.” I guess the generosity of the line in Spanish may well make up for the capitalization of content words in English. Stretching this compensation, we could also amuse ourselves by believing that the presence of the harsh “j” velar sound and the rolling of the approximant double “r” in Spanish are satisfactory equivalents, and carry over the stress-timed nature of the English language. Some kind of poetic justice of the heart.

On “carrying over”—I am sure you can help me with this:

I want to carry you

and for you to carry me

the way voices are said to carry over water.

This stanza is from the poem “Carry.” My challenge was the phrasal verb. Still these days I hesitate after lots of dictionary work, and native speakers’ on-their-feet reactions to this word combination. Voices can transport water, or voices can travel through water? I eventually chose the rippling through version.

A similar dilemma appeared in one poem by Sharon Olds and her “student-of-war” self-perception amidst her family. But that is a long story… Collins claims that the problem with poetry is that it encourages the writing of more poetry, and this process will not end until “we have compared everything in the world to anything else in the world.” As Walter Benjamin might have put it: Impure translators, you have a task!