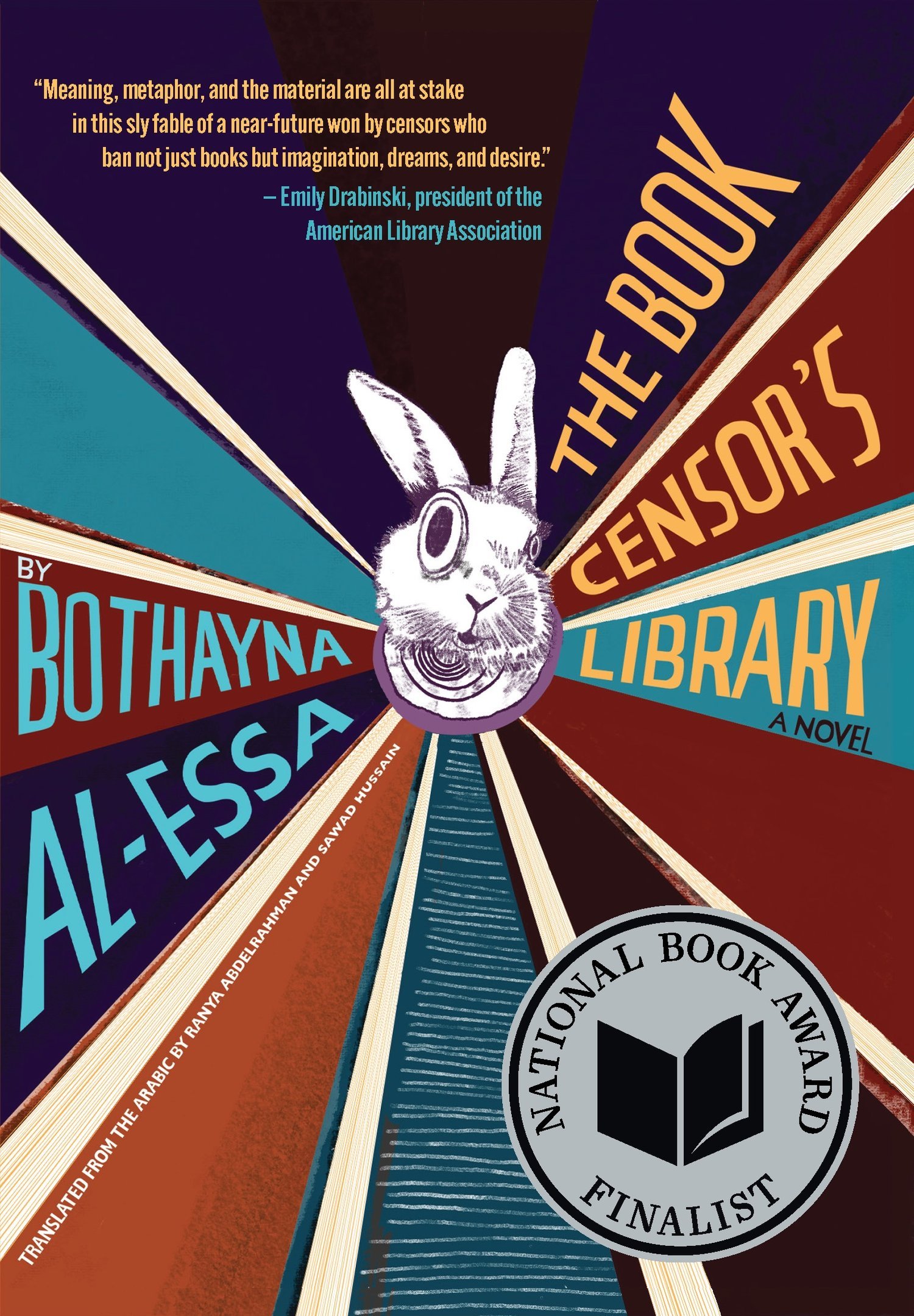

Review: The Book Censor’s Library by Bothayna Al-Essa

Translated by Ranya Abdelrahman and Sawad Hussain

Review by Emma Murray

Restless Books, 272 pp., $18 (paperback)

On one hand, the National Book Award in Translated Literature finalist The Book Censor’s Library is heralded as “a love letter to stories and the delicious act of losing oneself in them.” Yet, on the other hand, its purpose as a warning tale whirs, wails, unable to be ignored.

Written by Bothayna Al-Essa, a bestselling Kuwaiti novelist, and translated from Arabic by Ranya Abdelrahman and Sawad Hussain, The Book Censor’s Library reckons prudently with the global threat to free speech. “The events of this story happen sometime in the future, in a place that would be pointless to name, since it resembles every other place,” the novel’s front pages read. The unnamed protagonist is a new book censor who works at the so-called Ministry of Truth, tasked with reading manuscripts and flagging any elements that would make a book unfit to publish (such as: contradicting logic, using the word “internet,” threatening public order, referencing the “Old World,” queerness, unapproved religions, to name a few). Before long, this new book censor is recruited to join a group of resistance fighters working to preserve history and undermine the authoritarian regime.

All told, The Book Censor’s Library is in smart conversation with Orwellian dystopias, Kafkaesque surrealism, Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland, and many other seminal and portentous texts—not only showing how literature changes a reader, but also how a future without literature (or stories, or imagination, or any sort of free-thinking) is certifiably, depressingly bleak.

The English translation oscillates nimbly and neatly between past and present tense, revealing clearly and fluidly how this new book censor’s life has unfolded—he’s a husband, a father, and soon a recruit for the “Cancers,” the covert resistance group. From its first paragraphs, the novel runs with thrilling force, as though it grabs the reader by their lapels and drags them into this new world created by Al-Essa without letting go:

“The door slamming. Left alone with books. He’d been scared but hadn’t wanted to reveal how vulnerable he was. He knew things his wife wouldn’t believe, things the other censors didn’t yet appreciate. Books could hear, bite, multiply, have sex. They had sinister protocols to take over the world, to colonize and conquer—word by word, line by line, poisoning the world with meaning. But he was meant to only skim the surface of language. He thought he’d had enough training to sidestep the hazards of the job. The image of the First Censor drumming the table came to mind, his words unforgettable: All language is smooth. There are no ripples. Stay on the surface, and you’ll be the best censor.”

In an interview with Words Without Borders, Al-Essa said The Book Censor’s Library was inspired by her own life. “I am also a bookseller who has to deal with inspectors and censorship every day,” she reported. “I always wondered what it felt like for people censoring books. How are they managing to not fall in love with the books that they are supposed to ban or censor? Or how does it really work in their heads? So I thought of writing the story about a book censor who falls in love with a book that is supposed to be banned.”

The novel’s Ministry of Truth also derived from real-world experiences, modeled after Al-Essa’s experience with Kuwait’s Ministry of Information. “When it comes to censoring books … they always go for literal meanings and they don’t allow a margin for interpretation … most of the time, [they] have no idea what the book is talking about,” she said. “So I was fascinated by this idea that censoring books is not even close to the practice of reading, even though we have two people physically doing the same thing, scanning words with their eyes.”

Translation, yet another form of scanning words with eyes, calls for a special kind of optical intake and processing. From this, new products, new words, new worlds are created—and in this way, an original text is transformed into another text, somehow the same and yet different in innumerable ways. All translators must pay attention to censorship, whether as a subconscious act or something happening at an industrial level.

In an essay anthologized by Kavita Bhanot and Jeremy Tiang in Violent Phenomenon, Hussain notes how her translation practice is designed to curb a particular, more subtle form of censorship: the domestication of translated texts, rendering them as palatable as possible for U.S. audiences. “I am challenging the language hierarchy in translation,” Hussain writes. “Even if it makes you, the English or American reader, feel unsettled, uncomfortable, angry even—I still won’t cater to you. I am going to translate this book being as respectful as I can to the source text, and that means you need to get on this train before it leaves the station.”

Ranya Abdelrahman told Words Without Borders “one of the most interesting and challenging aspects of translating this book was dealing with the intertextuality. It’s full of literary Easter eggs, and we did our best to chase these down and unpick them to help inform our translation.”

Throughout The Book Censor’s Library, Al-Essa finds so many different ways to refer to other dystopian works, “say by echoing sentence structure or a particular scene or using certain words, and some of these allusions are multilayered,” Abdelrahman said. “For example, in a nod to the way language is stripped of all nuance in 1984‘s Newspeak, censors in the book are told to consider words and formations in pure isolation and avoid all ideas and interpretation. But this is also a play on, or actually an inversion of, a rhyming Islamic legal maxim which prioritizes intent over literal language in contracts. And we tried to bring a hint of the original into English by making the translation rhyme too.”

The resulting English text thrums with life and satisfying allusions. And though neither physical descriptions nor geographic names exist in the book, its desert-coded metaphors, the child calling for “Baba,” and rhythms in the characters' dialogues altogether maintain the bright feel of Arabic throughout the tale.

Given threats (and acts) of censorship exist and are growing around the globe, The Book Censor’s Library’s intertextual conversation goes beyond literary masters, into current political conversations—reckoning with today’s pressing questions about what it means to think critically, empathetically, originally.

As one of the Book Censor’s resistance comrades says: “When the world is this abysmal, getting used to it is the worst thing that can happen to you.” Instead, he implores, read. Then you can open your mind.

-

Emma Athena Murray is a writer, editor, and translator of Spanish literary works. After seven years as a journalist reporting at the intersection of geography, public policy, and social justice, she pivoted into and MFA in Literary Translation and the truth-telling spheres of world literature. With a double-BA in Philosophy and English from Brown University, she continues to interrogate the world through written words. Her research interests include both contemporary and 16th-17th century female voices from Latin America; how feminine rage manifests in literature; the alchemic powers of translation; and autotheory as literary craft.