Slippage

A Painting That Is Worth Ten Thousand Words

Yuemin He translates from the Chinese.

A Painting That Is Worth Ten Thousand Words

Translated from Chinese by Yuemin He

Poem 9

What is the point of

pressing a big gourd against a catfish

Catch or no catch

it brings just a smile or amusement

Poem 11

Grab a gourd and use it

to catch a catfish in the muddy river

If hand and heart are perfectly timed

that’s like pressing down the water

Poem 12

Your imperial majesty could not be kinder

your benevolence blesses even a catfish

There is no need for legendary power

for a gourd to reign over a river

Poem 13

What can be so slippery

but the tail of a catfish

If a big gourd cannot pin it down

It’s merely the water’s fault

Poem 14

Pulling and pressing the catfish

when shall the round gourd stop

It is so laughable

No misbehavior allowed at the shogun’s presence

Poem 22

The whole catfish is scaleless and slippery

knocking the gourd around like a wheel

As hard to catch as a mischievous brat

it hides left and right to stay unscathed

瓢鲇圖

Poem 9

按鮎何所图,

用个大葫蘆。

捺住捺不住,

唯供一笑娯。

Poem 11

葫蘆提起去,

泥裏逐鮎魚。

心手如相应,

何如捺著渠。

Poem 12

聖朝恩沢余,

游泳及鮎魚。

不費孟賁力,

葫蘆捺住渠。

Poem 13

何物甚流滑,

合無鮎尾如。

大瓢難捺著,

放下只嗔渠。

Poem 14

瓢團圝鮎撥剌,

捺著何時休歇。

咲它作這去就,

大人前莫輕忽。

Poem 22

鮎魚舉體滑無鱗,

瓢子捺来如轉輪。

又似童奴頑且孏,

左逃右避動抽身。

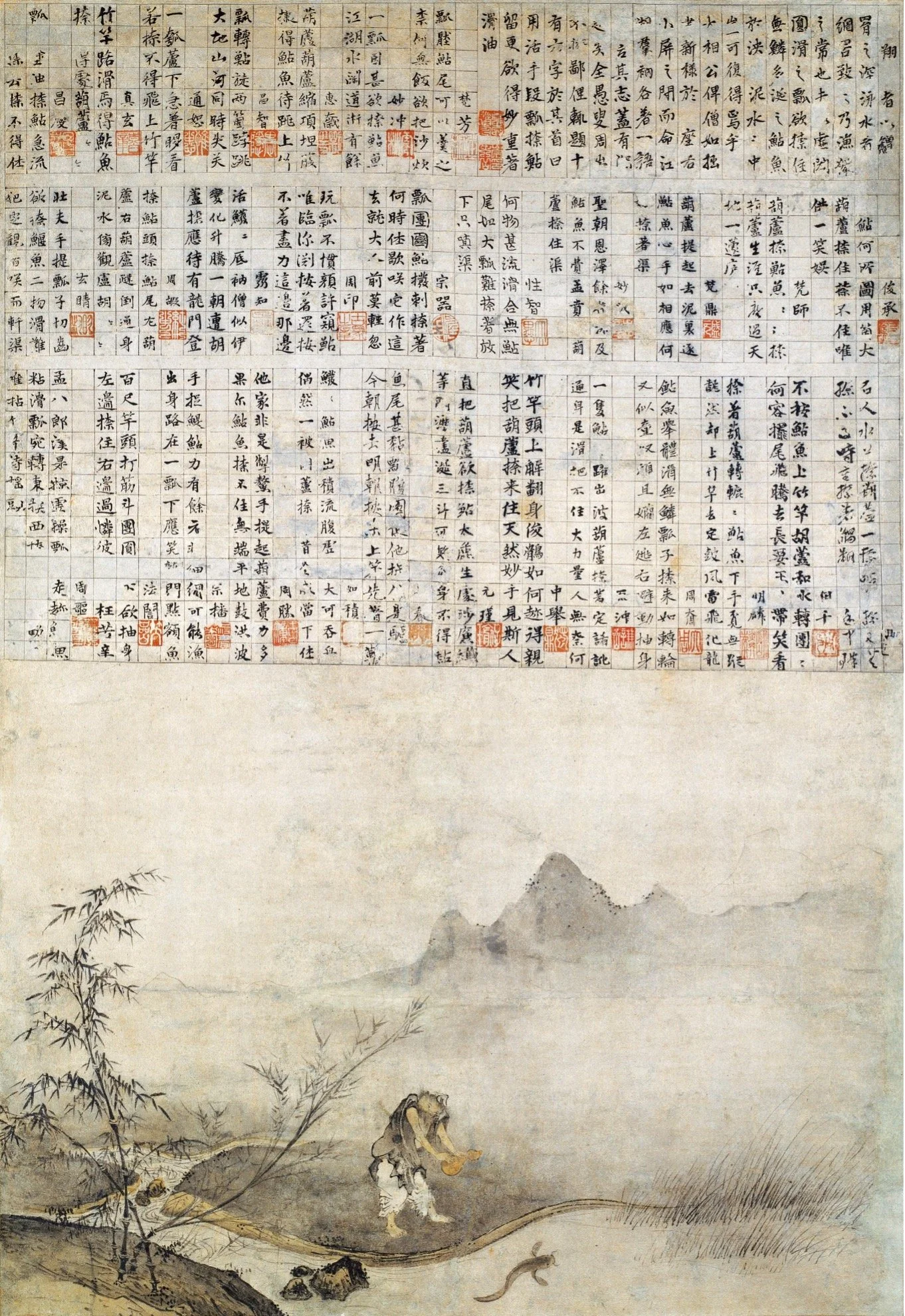

National Treasure国宝, 退蔵院

紙本墨画淡彩

Dimensions:111.5cm × 75.8cm

時代:1413年前後

Translator’s Note

The above painting, titled The Gourd and the Catfish/瓢鲇圖, was done by Taikō Josetsu/如拙, a Zen monk active during the Muromachi period (1336-73). It features a male with an unkempt look, standing on a winding riverbank, holding a gourd in his hands, and attempting to capture or pin down a catfish swimming in the stream. Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimochi/将军足利义持 (1386-28), a connoisseur of Zen koan and patron of Kyoto’s Zen monasteries, asked Josetsu, the chief priest of the Taizoin Temple of Kyoto, to paint a riddle, “How does one catch a catfish with a gourd?” Yoshimochi also asked the best monks from the five top Zen monasteries (gozan/ 五山) of Kyoto to reflect over the situation. Each monk wrote a poem to respond to the riddle/應答詩, totaling the 31 poems on the painting. Poems 1-8 are four characters per line; poems 9-13 are five characters per line; poems 14-18 are six characters per line; poems 19-30 are seven characters per line; and poem 31 defies categorization due to lost characters. These poems are “jocular” and “witty” and even “mischievously” funny. Responding to the riddle or koan, which seems paradoxical and enigmatic, they embody the efforts of the monks to intuitively unravel the conundrum of the imponderability of the mind that is conveyed in a most absurd picture.

Zen Buddhism originated in China, as Chan, and the original scriptures were written in Chinese and transmitted to Japan in this form. The Japanese monks continued to use the Chinese writing system for centuries until mixing the Chinese characters Kanji with the Japanese syllabaries Hiragana and Katakana. This Chinese influence also shows in the poems the monks wrote. The poems are all written in the form of classical Chinese poetry, with fixed number of lines—in this case, all four end-stopped lines, varying from four characters a line to five, six, or seven characters—and with end rhymes. Due to different language nature, instead of using end rhymes (Poems 13, 14, and 22 fail to rhyme anyway) and all end-stopped lines, I translate the poems into today’s English with enjambment and rely on alliterations and sentence pattern for fluency, sound effect, jocular tone, and funny images. The goal is to capture the spirit of these poems and deliver reader-friendly translations.

For example, a functional translation of poem 9 may look like this

Why press against a catfish

Use a big gourd

May or may not catch the fish

Only entertain or elicit laughter

This rendition sounds choppy because none of the original lines contains a subject, which is, however, fine in the Chinese original and an ordinary characteristic of the classic Chinese language. Also, the first three lines in the original poems rhyme, but as this translation shows, it is almost impossible to recreate that. Whereas, in my translation, I stop the first line at a natural breath group, “what’s the point of,”and follow that with a gerund phrase, “pressing a big gourd against a catfish.” This makes the first two lines not only raise a question but also reflects the couplet nature of the original first two lines with coherence. My translation of the last two lines reads crisply and clearly, and it offers a nice explanation to the question formed in the first two lines. Has my translation achieved the dynamic equivalence Euguene Nida talks about? I am not sure, but it certainly carries over the meaning and bantering tone.

The painting is truly Zen in subject matter. Besides being Zenkizu/禅機圖 (a painting of incidents and encounters taken from the Zen textual tradition), the painting is also a poem-picture scroll, or Shigajiku/詩畫軸 (a painting that is accompanied by poetry and has its roots in China and where the painting and the poetry are inherently connected). Only four poems, all four-character quatrains, have been analyzed by American scholars. I have translated another six poems to help unfold more of the painting to the English readers. This act of unfolding helps perform how a poem-picture scroll was unfolded back then—with reverence and gentleness, slowly unrolling from right to left, or top to bottom, revealing one section at a time to appreciate the unfolding narrative or landscape. It also expands the long American scholarly study and translation of Eastern and Buddhist literature, which has broadened the field’s cultural and aesthetic horizons. These six poems, though humble in number, will certainly contribute to the growth of American Buddhist literature. My wish is that more English translations and study of Josetsu’s painting will occur.

As a Japanese national treasure, the painting is worth not a thousand words, but ten thousand words.

-

The painting, The Gourd and the Catfish/瓢鲇图, was done by Taikō Josetsu/如拙, a Zen monk active during the Muromachi period (1336-1573). The authorship of the poems visible in the painting is discussed in the Translator’s Note

-

Yuemin He is the recent winner of The Jules Chametzky Prize from The Massachusetts Review.

Her poetry translations have been anthologized or published in more than thirty literary magazines and journals, including The Cincinnati Review, Copper Nickel, and The Southern Review. Her first book of poetry translations, I’ve Seen the Yellow Crane, was released in 2024 (Foreign Languages Press). Her work was also longlisted for Best Literary Translations 2026 anthology by Deep Vellum.