Translator's Note

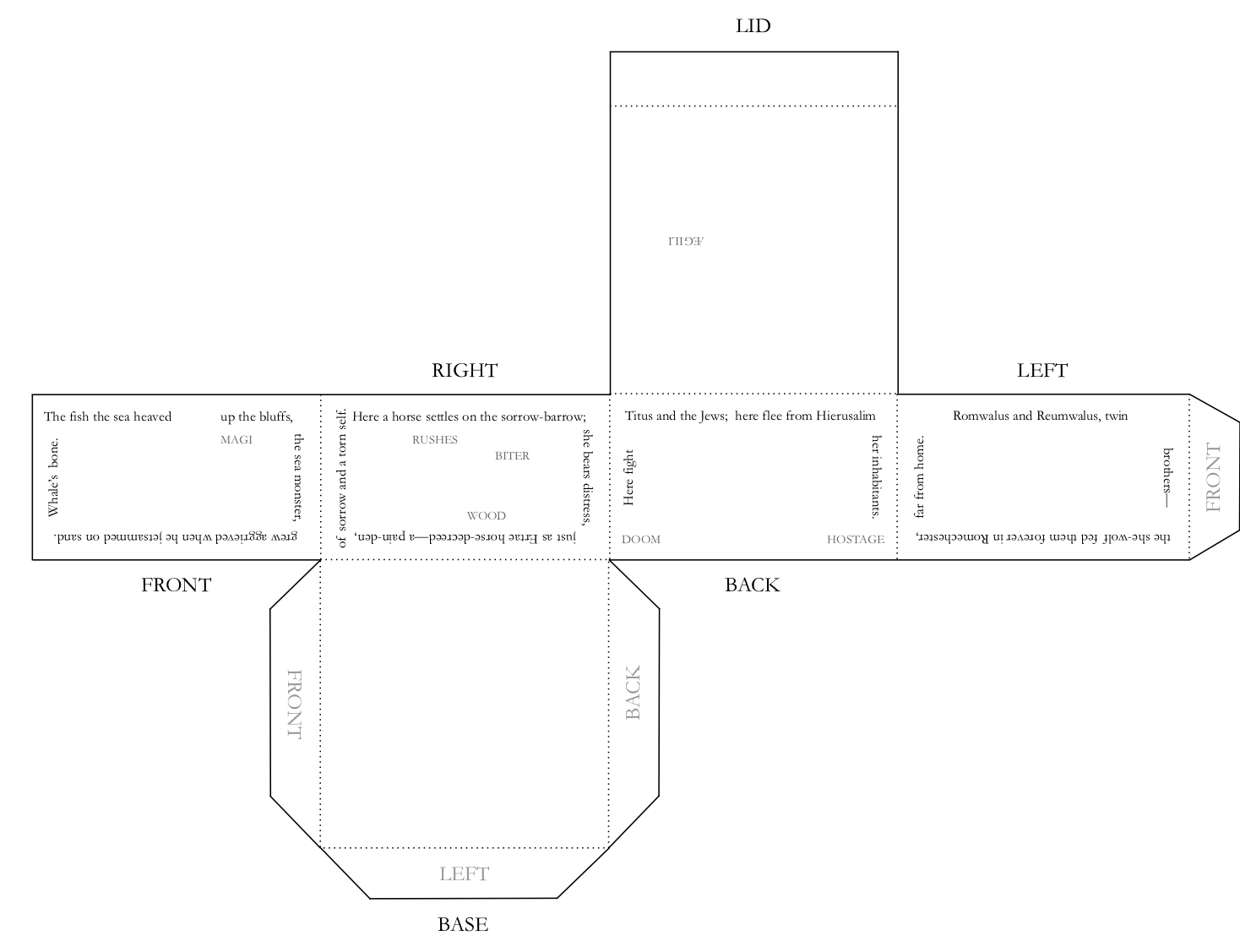

In this piece, I have translated the Franks Casket in the format of a printable net which can be cut, folded, and glued such that it forms a miniature rectangular prism resembling the original casket’s shape. As a kid, I was fixated on making paper models of polyhedra, and a recent opportunity at work to lead a similar activity with students inspired me to connect that craft with my love of ancient literature. For me, one of the most interesting parts of studying ancient texts is the materiality of it all. Many texts survive as a part of objects not solely intended for carrying text. The physical situation of language on such an object has a real impact on a reader. What is the object for, and how does that functional context affect our reading? How are our visual, spatial, temporal, and kinesthetic experiences of reading affected by the object? I find it dissatisfying when texts that originated on tiny brooches or monumental steles become flattened into book or webpage format when presented for a contemporary audience’s consumption. With this project, I aim to recover some of those physical elements of the Franks Casket in the very form of my translation, by forcing the reader to physically handle and rotate it as an object, craning their neck to experience its various panels and read its inscriptions.

The Franks Casket’s text is difficult and obscure. I am indebted to Martin Foys’ Franks Casket: A DM Edition, an online edition using the Digital Mappa digital humanities platform; my translation is based on his transliteration of the Casket’s runes, and I leaned heavily on the thorough critical commentary he compiles for every single word on the Casket. Wherever I’ve made a contentious reading, my choices are made more from artistic considerations than philological ones. Though obviously I have had to make interpretive choices in translating this text, my preference as a reader is to dwell in the possibility and indeterminacy of the many readings that have been proposed.

The three-dimensional nature of this translation also attests to the fact that it can be read in many ways, both in terms of the order of the casket’s different panels and the sequence of the inscriptions which frame each panel. Though scholars disagree about which side of each panel to read first, my translations are intended to be read clockwise starting from the top line in all panels except the rear, which begins from the left. The panels can be read in any order, but I recommend encountering them in the order that a museum visitor, French seamstress, or Anglo-Saxon monk may have encountered the panels of the real thing: starting with the lid, then the front, and then circling around to view the right, back, and left panels.

The lid has the briefest text of any of the panels. Its illustration features an image of an archer. His label, Ægili, has sometimes been interpreted as indicating Achilles, but the broader consensus is that he is Egil, a hero from Germanic folklore.

The front panel is my favorite. Its alliterative verse inscription is a tribute to the whale whose bone was used to make the box. That inscription imagines the interiority of the whale sensitively, and treats the creature with awe. Its moniker, gasric, is a hapax legomenon (a word not attested anywhere else in the Old English corpus) which I render “sea monster” in a triangulation of divergent scholarly readings of the word, either as meaning “terror king” or as a form of the word for “ocean.” This poem’s striking and terse conclusion—“Whale’s bone”—can be read simultaneously as a kind of colophon indicating the box’s medium, and as a brutal volta with the force of a smash cut. This panel is illustrated with a scene from Germanic folklore, as well as the Magi from the Gospel of Matthew, who receive a helpful label.

The right panel is complicated and controversial, not least because it uses a unique system of ciphered runes, which replace many vowels with nonstandard forms. I make no real attempt to solve it. I read Old English hos as horse, mostly because this matches the illustration of a horse nicely, and maintains the motif of unhappy animals from the front panel. The horse is labeled bita, “biter”—the other small-font nouns on that panel also label elements of the illustration.

The rear panel is most fascinating for its combination of Old English and Latin, featuring one sentence in each language, and one Latin word spelled phonetically in runes (afitatores for habitatores). This linguistic and orthographic pluralism is lost in my one-language, one-script translation. I do not amend the scribe’s spelling Hierusalim to modern “Jerusalem” because I am interested in the reception of classical material on the Franks Casket. The Casket’s text remembers those times and places in a way particular to its own time and place, and I want to be faithful to that particularity.

The final panel features Romulus and Remus, whose names I have also left in the spelling the Casket’s scribe used. This also retains the amusing double meaning, identified by Foys, behind Romwalus: the “ironically fitting meaning of ‘stranger to Rome.’” Most scholars read Romæ cæstri as two separate words, “the town of Rome,” and I am probably of the same opinion, but I render it here as one word because “Romechester” made me giggle.

While I hoped that my translation could be faithful to some of the materiality of the original casket, I am aware of the impossibility of replicating the Franks Casket in modern English, and was interested in approaching the project with a tongue-in-cheek demeanor. As an artist and educator, I hope to prioritize play and pleasure in my work. In that spirit, I hope to invite the reader into the experience of the translation in an explicit way by asking them to physically construct the object that houses the text, even drawing their own illustrations that reflect their reading. At the same time, the Franks Casket’s actual content makes this playful attitude fraught: on its back panel, we encounter explicit imperial violence against Jews, and our cute art project ends up literally marked with the legacy of empire. This tension is a microcosm of how we engage with ancient literature: if it’s a source of enjoyment, it must also be an object of careful, sharp criticism. I hope that the interactive nature of this translation will create the space for readers to both enjoy and critique the Franks Casket.

Acknowledgments

I first encountered the Franks Casket in an Old English reading group hosted by Dr. Ian Cornelius; I want to thank that entire group, which is still the most indulgent, curious, and enthusiastic academic environment I’ve ever been a part of. I hope you’re all thriving. I also want to thank my coworker Dr. Chaim Goodman-Strauss, whose beautiful polyhedral nets inspired this project. In addition to Foys’ excellent edition, I also consulted Leslie Webster’s The Franks Casket (British Museum Press, 2012) and “Old English in Material Context” from Peter S. Baker’s Introduction to Old English (John Wiley and Sons, 2012). All errors and questionable choices are of course my own.

Carl Lewandowski