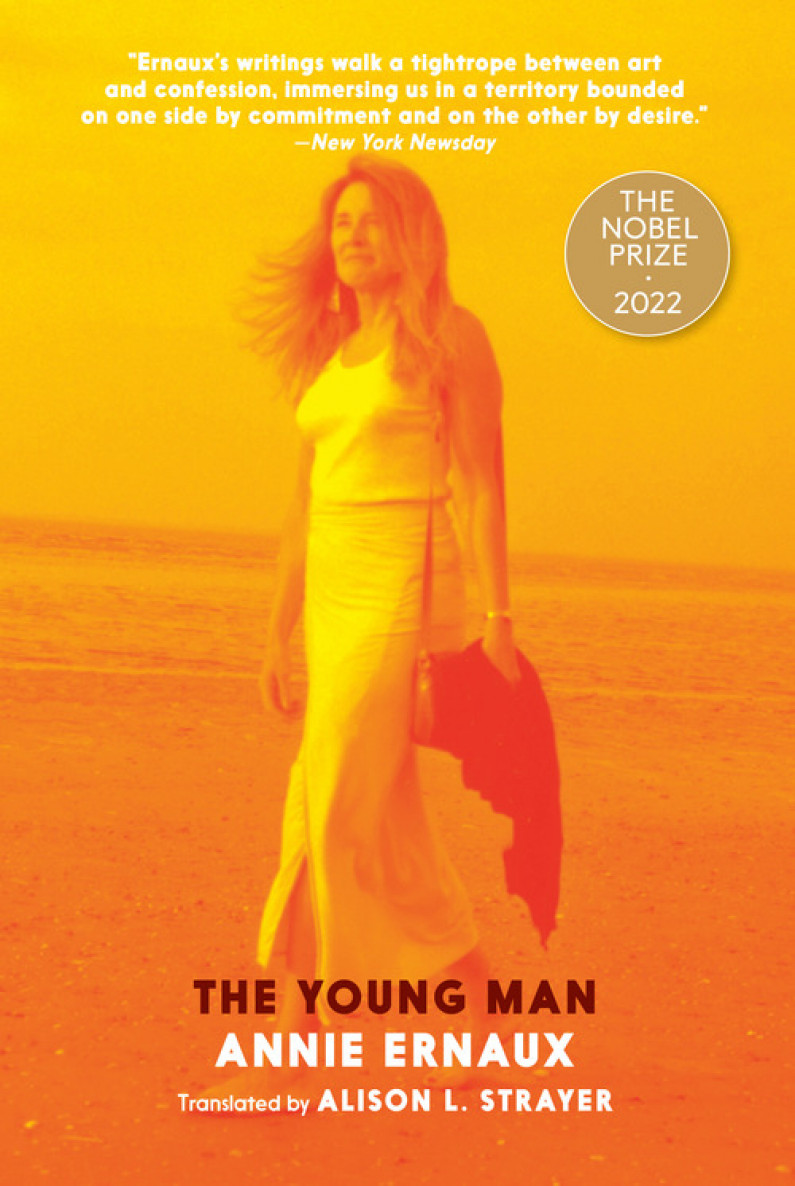

Review: The Young Man

The Young Man

By Annie Ernaux, translated from the French by Alison L. Strayer

Seven Stories Press, 62 pp., $13.95 (paper)

Review by Jacquelyn Bengfort

Seven Stories Press has served as Annie Ernaux’s American publisher since the early 1990s, and published Getting Lost, the English translation of Se perdre, just days before the announcement that she won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Literature. In 2023, they published two more Ernaux books: I Will Write to Avenge My People, her Nobel lecture, and The Young Man, published originally by Gallimard as Le jeune homme in 2022.

The Nobel Prize often serves to introduce important writers to a broader global audience. For me, this was indeed the case; I was unfamiliar with this French writer admired in her own country for her slim and powerful volumes of autofiction. As a long-suffering autodidact with a love for the French language, I saw too an opportunity to further my own education, quickly selecting her L’occupation as a starting place in her considerable catalog and laboriously translating it, comparing my amateurish results (I had not yet gotten to past or future tense verbs in Duolingo!) to those of Anna Moschovakis, whose translation Seven Stories Press published as The Possession in 2008. When I later came across a brief story by Ernaux in The New Yorker, translated by Deborah Treisman, near the end of 2022, I was pleased to find Ernaux’s style still ringing out on the page.

It is this style—an immense clarity, an almost superhuman exactitude—for which Ernaux is known. She deploys even-handed prose to deliver an honest account of experience, a precise portrait of human being. But directness of style, and the close relationship between French and English, does not leave the translator without decisions. One of the pleasures of reading The Young Man in translation, for me, was exploring the choices Alison L. Strayer makes, which themselves constitute a catalog of techniques available to practicing translators.

I have found Strayer to be exquisitely attuned to the demands of the text, carefully deploying different approaches from moment to moment. Terms that are easily glossed she sometimes leaves untranslated: bourge remains bourge, for example, since most English readers will be familiar with the meaning of the term “bourgeois,” and this knowledge combined with the context available in the sentence makes its meaning clear:

With my husband, I had felt like a working-class girl; with A., I was a bourge. (24)

Other moments call for a more complex treatment. The titular young man is given to idiomatic language, and his French is riddled with English borrowings and non-standard terms. In just two lines on page 22, Strayer lets “stop” remain “stop,” “c’est bon” becomes “that’s good,” and “la meuf” and “la reum” remain intact, awarded a brief explanatory footnote for those readers unfamiliar with verlan, a French slang that plays with letter and syllable inversions. In the case of longer idiomatic expressions, she sometimes opts for wholesale substitutions, selecting an English expression similar in spirit; at other moments, she selects an idiomatic English phrase where direct translation would be possible, but stilted; another time, she might closely match the syntax of a sentence in a way that sounds slightly unusual to an English speaker but is easily parsed. The result of her careful choices is a volume that allows us to experience the various textures of the original in the translation.

The book itself is cleverly metafictional. It’s hardly a new observation that women artists who work explicitly from the circumstances of their own lives are often charged with engaging in love affairs for material (Taylor Swift, anyone?), but Ernaux leans into that idea from the first page, musing, “Often I have made love to force myself to write… Perhaps it was the desire to spark the writing of a book--a task I had hesitated to undertake because of its immensity--that prompted me to take A. home for a drink after dinner.” A reader might be forgiven for suspecting the very book she is holding is that the affair prompted; Ernaux’s process is far more complicated, however, as readers soon learn.

What follows is a dissection of the affair. Sex is alluded to, but Ernaux lavishes her attention rather on the intellectual and emotional impacts of the time she spent with a lover almost thirty years younger than she. We are offered intimate access to the mind of a self-identified menopausal woman dating a man roughly the age of her own adult children. Ernaux sensitively explores the ways seeing the young man changes her own psychology, how the relationship changes when they are publicly perceived and judged. The affair becomes a vessel for the examination of the nature of time, space, and story itself. There is no question that a clock ticks for each of them: he wishes for children, while she is uninterested in the complicated logistics of having a baby in her mid-50s. His adult life awaits him; she grapples with her mortality.

Seven Stories Press took the opportunity of this book’s post-Nobel publication to offer an introduction to Ernaux, adding several photos and a brief autobiography not present in the Gallimard original and no doubt meant to catch new readers up on her long career. And The Young Man is a perfect initiation into Ernaux’s greater project; taking less than an hour to read, it introduces the reader to major themes and concerns in her writing, even pointing back to the genesis of one of her major works (which one, I won’t say here). But, perhaps most importantly, this short book leaves you with the uncanny sense that you have lived as someone and in sometime else, if only for a while.

–

Jacquelyn Bengfort was born in North Dakota and holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, an MPhil from the University of Oxford, where she was a Rhodes Scholar, and a B.S. from the U.S. Naval Academy. Her creative work has been supported by a Rona Jaffe Graduate Fellowship, three individual artist grants from the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, and a scholarship from the Martha’s Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing. Jacquelyn is the author of the Ghost City Press micro-chapbooks Navy News Service and Suitable for All Methods of Communication. She lives in Iowa City with her spouse, children, and a dog named after a prominent Canadian mystery writer, and teaches creative writing as an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Iowa.