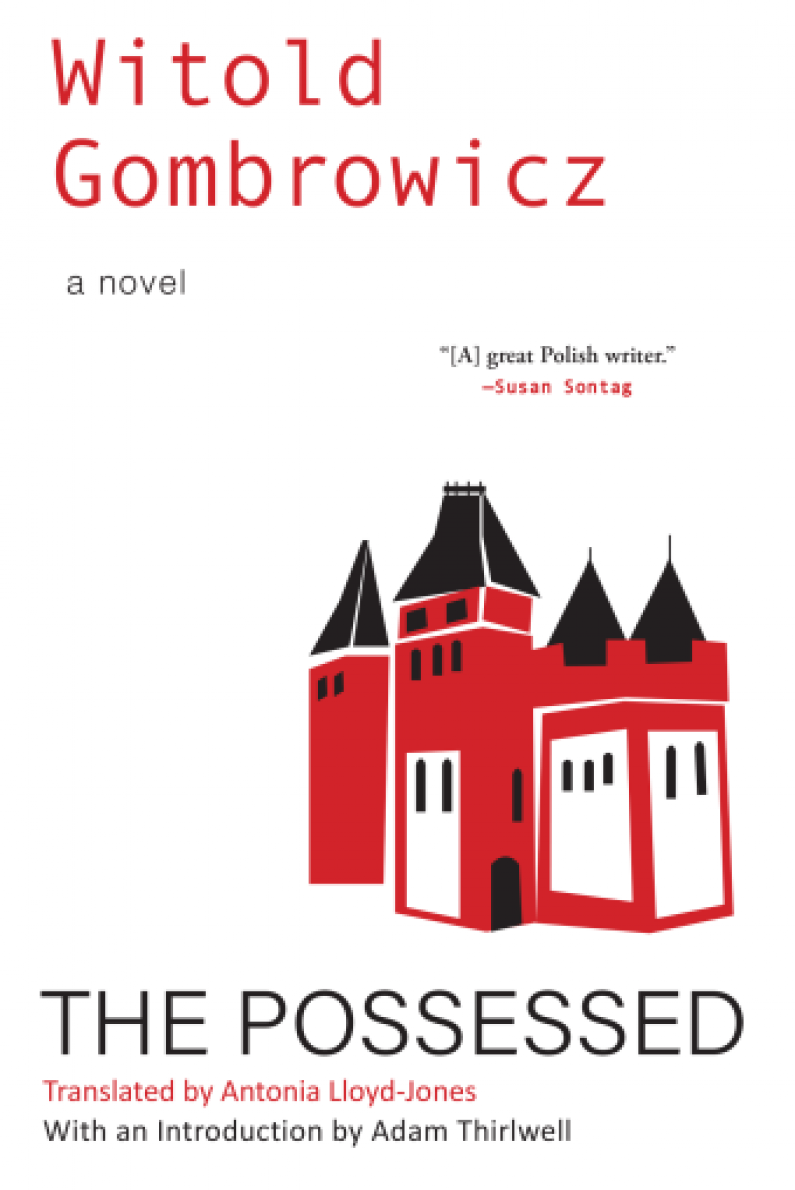

Review: The Possessed

The Possessed by Witold Gombrowicz

Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Introduction by Adam Thirlwell

Black Cat, 416 pp., $17.00 (paper)

Review by Eric Vanderwall

In late July 1939, Polish author Witold Gombrowicz accepted an invitation from the Ministry of Industry to travel on a new cruise ship’s maiden voyage across the Atlantic, from Gdynia, Poland to Buenos Aires, Argentina. Gombrowicz was then thirty-five years old, enjoying the commercial and critical success from his 1933 collection of short stories, Tales from the time of Immaturity (later republished as Bacacy) and his 1937 novel Ferdydurke. He was at the beginning of what promised to be a rewarding career in letters. But less than a week after the ship docked in Buenos Aires, Germany invaded Poland, and Gombrowicz remained in Argentina for the next twenty-four years. He never returned to Poland.

The war truncated not only Gombrowicz’s early authorial successes, but also the serial publication of his novel The Possessed, which ceased on September 3, in the midst of the Nazi invasion. The Possessed takes the form of a pastiche in which gothic tropes collide with the trappings of 1930s Poland. The novel opens on a train “somewhere beyond Lublin,” travelling into rural Poland. On board are Marian Walczak, twenty-year-old tennis coach; Maja Ochawołowska, a young woman from an aristocratic family of declining fortunes, who will be his pupil; the mad Prince Holszański; Cholawicki, Ochawołowska’s fiancé and the conniving secretary to the addled old prince; and Professor Skoliński, art historian keenly interested in what art treasures might lie hidden in the mad prince’s crumbling ancestral castle. All soon find themselves in remote Połka, where Holszański’s castle looms over the Ochawołowska estate, now lodging vacationers to improve the family’s dwindling wealth. Early chapters are replete with secrets revealed in purloined letters, scenes of confession secretly witnessed from closets, scheming heirs, bickering boarders, and rumors about a curse on the mad prince and his gloomy castle. The adherence to gothic conventions is thorough.

There are, though, indications that The Possessed is not merely the record of a youthful Gombrowicz’s foray into a familiar form. For one, frequent coincidences and convenient exposition through found letters and stilted conversation suggest, perhaps even to the reader new to Gombrowicz, that the exhaustive checking off of tropes is cheeky rather than earnest. The biggest clue that some, or all, is meant in jest, comes at the end of the second chapter, when Walczak is abruptly renamed Leszczuk. An editorial footnote, which appeared in the original serialization, explains that “there has turned out to be a real tennis coach named Mr Walczak,” and “with the author’s permission,” the character’s name has been changed to Leszczuk. “What a strange coincidence!” What a coincidence indeed. In a bracketed translator’s note, and at greater length in an interview with Shakespeare and Company, Lloyd-Jones explains that this textual disruption was very likely a prank played by Gombrowicz on the editors (and readers). This metatextual disruption, although unique in Gomrbowicz’s novels, is characteristic of his lifelong subversion of form. For The Possessed, the name shift and editorial intrusion upset the apparently straightforward gothic novel and, more profoundly, the conventions of narrative immersion, continuity, and verisimilitude that characterize modern fiction, and realism in particular. The Possessed is neither serious gothic, nor serious gothic parody, but something else that partakes of each.

As the earnest and parodic gothic elements develop, readers accompany first Cholawicki and later Skoliński into the castle’s depths, to the allegedly haunted old kitchen. “Anyone can tell at once there’s an evil force in here,” Holszański’s loyal butler Grzegorz warns Cholawicki. And what is the sign of evil forces at work? An old towel, “grey with dust, hanging on an old iron peg,” quivers while remaining taut, “as if an invisible hand were holding onto it from below.” There is “something horrible about it,” this towel that elicits “a nasty feeling,” a “vague but acute sense of atrocity.” The reader too feels this unease, this dread, this anxiety, while also noting the silly, underwhelming effect of a towel being the harbinger of evil, a duality that well exemplifies Gombrowicz’s simultaneous earnestness and sarcasm. The fixation on a banal item as a locus of evil and depravity prefigures similar concerns in Pornografia (1960), in which a crushed worm initiates a series of bizarre associations and correspondences that lead ultimately to murder, and in Cosmos (1965), with its fervid search for meanings in wall stains and refuse piles.

At about the midway point in the text, when Leszczuk runs away to Warsaw and Maja follows, the gothic setting and tropes are temporarily left behind as the narrative focuses on the vicissitudes of life in the modern metropolis. This middle section of the work feels at times almost like a separate novel, with Leszczuk attempting to break into the world of professional tennis and Maja falling in with a Russian émigré and the young women she puts to work as escorts. Gombrowicz’s focus on tennis as emblematic of modernity and youth recapitulates some aspects of Ferdydurke, although here Leszczuk’s competition with professionals at exclusive clubs is part of a dramatization of social class in flux: orphaned and impecunious Leszczuk tries to raise his status through sporting skill (and some ethically questionable trickery with specially strung rackets) while Maja attempts to retain ties to the wealthy élite as an escort (whose expected duties may be more than she wishes). The way this middle section strays from the initial concerns of the novel into amusing but seemingly unrelated episodes bears the marks of the serial form’s requirement for hooks and climaxes in each installment.

Following a locked-room murder that implicates Maja and Leszczuk, the two flee Warsaw for Połka. On her way there, Maja, through a fortuitous (and narratively convenient) coincidence, happens to meet “the famous Warsaw clairvoyant” Hińcz, who “really was distinguished by some mysterious sense inaccessible to other mortals.” Lesczuk’s left-behind, and nervously chewed, pencil, in the hands of the seer, reveals to him a confusion of images. Like the quivering towel, the pencil’s uncanny significance and power are simultaneously serious and silly. “I’ve never come across an object as evil as this pencil before,” Hińcz says. “It’s the worst thing I’ve ever held in my hand.” Once back in the countryside, Hińcz the clairvoyant and Professor Skoliński the rationalist, at first skeptical of one another, predictably team up to investigate all the nefarious goings on, both supernatural and mundane. Soon Hińcz and Skoliński conduct a séance with Leszczuk as medium, and the cryptic utterances he makes while possessed give the seer and professor enough clues to explain the quivering towel, the haunted kitchen, the prince’s tragic past and subsequent madness, and how these are all connected by a local peasant’s secret identity. These concluding chapters, including the recently rediscovered final three, spoof and adhere to the gothic form in providing both rational and supernatural explanations for the events. The towel, even after its quivering is explained, continues to unsettle Hińcz and Skoliński, who refuse to touch it. Behind the gothic tropes and literal possession, though, one still detects Gombrowicz’s sly humor and preoccupation with youthful obsessions leading to violence, motifs that receive more philosophically dense treatment in the later works Pornografia and Cosmos.

This English translation of The Possessed is the second, following the 1981 Marion Boyars edition (out of print), which was made from the French translation and not the original Polish. That edition, as well as those in Polish and other translations, were also incomplete, including only the portions of The Possessed serialized before the disruption of the war. It was not until the rediscovery in 1990 of the final three chapters, never before published and long presumed lost, that a complete edition could be compiled. The Possessed occupies a curious place in Gomrbowicz’s oeuvre, and not only because of the serial form (and its premature termination). The work originally appeared under the pseudonym Z. Niewieski, and only near the end of his life did Gombrowicz acknowledge authorship. And in comparison to Gombrowicz’s other novels (Ferdydurke, Trans-Atlantyk, Pornografia, and Cosmos), The Possessed is the least characteristic, the most unlike the others, all of which are narrated by manic, fervid, obsessive semi-autobiographical characters named “Witold Gombrowicz.” As such, The Possessed is more focused on plot events and less on the workings of a deranged, solipsistic mind vacillating between to abstruse musings about Form and violent compulsions. Ideas about doubling, inexplicable similarities, and the connection between youthful insouciance and violence, which Gombrowicz explored more fully in Pornografia and Cosmos, are present in germinal form in The Possessed, but the comedy and overall tone are is lighter.

The new English translation of The Possessed makes available to Anglophone readers an early, uncharacteristic work from the unclassifiable Gombrowicz. The complete text, translated directly from Polish, will be of most interest to scholars of relevant fields. Writers applying to their own craft the techniques of European modernism will be interested in how The Possessed illuminates more of the author’s development and his place relative to his literary forbears and contemporaries. Although The Possessed is not likely to lodge in readers’ minds and sound their emotional and philosophical depths as Gombrowicz’s other novels do, its pastiche and parody, melding of genres, and light (for Gombrowicz) irony make for an enjoyable read, and its addition to the corpus of literature by major authors available in translation is important for scholarly and writerly study.

—

Eric Vanderwall is a writer, editor, and musician. He earned his MA from the University of Chicago. He has released two instrumental guitar albums, Precious Memories and Take Time to Be Holy. His scholarly work has appeared in Philip Roth Studies and The Hemingway Review. His fiction has appeared in The Ekphrastic Review, Memoryhouse, Academy of Heart and Mind, Amazine, and elsewhere. His book reviews have been published in the Los Angeles Review of Books, the Star Tribune, Chicago Review of Books, On the Seawall, and elsewhere. Visit www.ericvanderwall.com to learn more.