Review: Sor Juana & Other Monsters

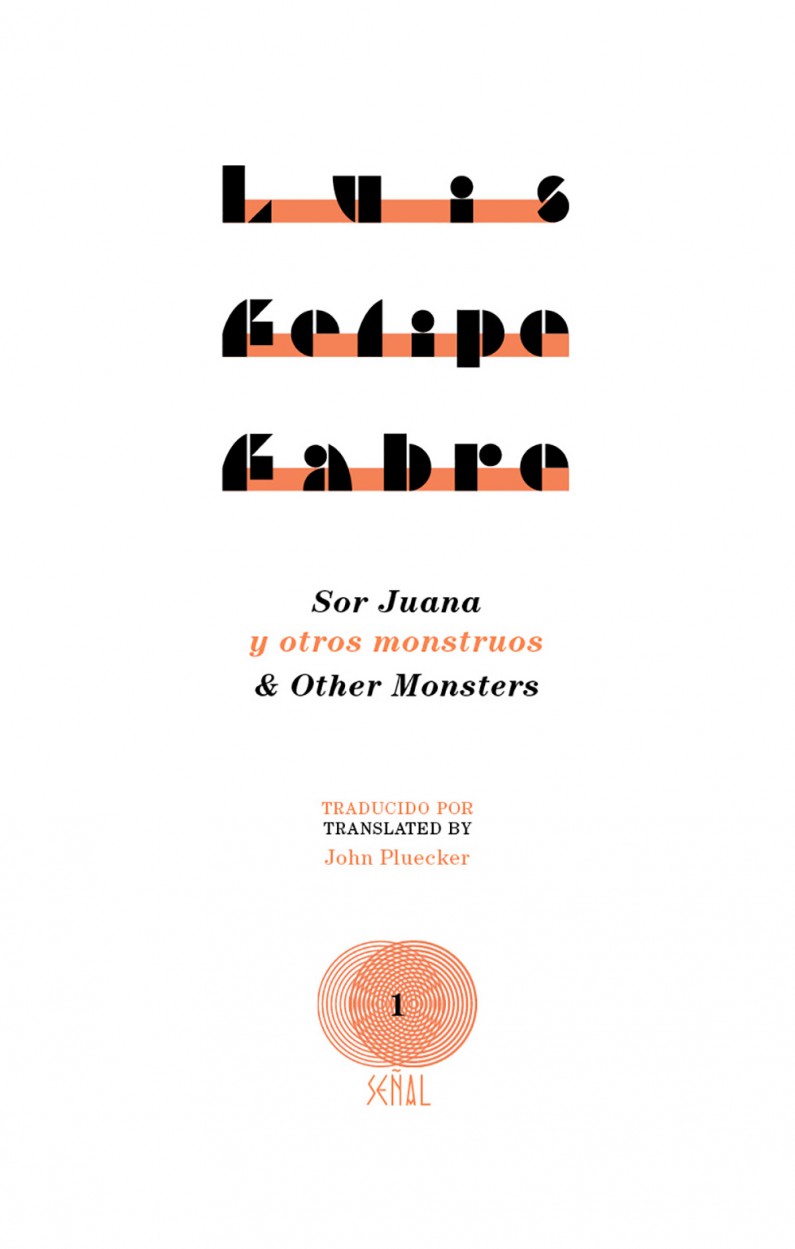

Sor Juana & Other Monsters, by Mexican writer Luis Felipe Fabre and translated by John Pluecker, is a lively first chapbook in Ugly Ducking Presse’s Señal series. The first half of the chapbook, a long poem entitled “Sor Juana and Other Monsters,” is a “spoof of an academic paper in verse,” about Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s so-called monstrosity, while the second half is comprised of the imaginative “Mashups” 1, 2, and 3, in which Sor Juana encounters monsters from the mythical cannon.

“Sor Juana & Other Monsters” is notable for the quirky, cheeky voice Pluecker inhabits. This involves keeping the translated poem fresh and fast-paced despite numerous repetitions. In contrast to the shorter “Mashup” poems following, Pluecker’s English rendition of “Sor Juana and Other Monsters” stays syntactically close to the Spanish, and mimics its line breaks almost exactly. There are only one or two lines that feel a bit stilted or obviously translated from Spanish in their syntax. Pluecker translates “ella misma advertirá / que todos esos epítetos la convierten / en un monstruo…” as “she will warn that all those epithets turn her / into a monster…” leaving ‘warn’ without a direct object, and creating a rather awkward use of the conjunctive form of ‘that.’

The true test of Pluecker’s mettle as a translator, it seems, was putting the “Mashup” poems into English. These are poems that rely heavily on rhyme to convey their darkly humorous tone, and Pluecker has rightly opted to use rhyme in his English translations. These translations are laudable for their creativity and flexibility—the way in which they modify syntax and find ways to rhyme while staying true to the spirit of Fabre’s poems. There is great delight in rhymes like “stampede/indeed” and “creepy/panicky,” or the use of the word “pasty” for the Spanish “pálida,” and, in fact, great delight in the fantastical possibilities of these poems’ content. Pluecker writes in his translator’s note that “Fabre’s poems do not seem to be afraid to be read as comic or burlesque” and this is just the tone achieved. He uses an extreme amount of -ly adverbs and words ending with -y to achieve what he calls the “fakery involved in the entire process.” Pluecker is having fun; he’s being playful with all the ghosts of Sor Juana, just as Fabre is.

Pluecker has also made choices in translation to allow the work, as much as possible, to remain in a Mexican context. He leaves “señora” and the name “Décima Musa” in the Spanish. Thanks to the translator’s note, the reader is also made aware that Pluecker went through many, many versions of Sor Juana’s work in translation as part of the translation process, and where Fabre used language appropriated from Sor Juana’s work, Pluecker nods to the many writers and readers who’ve likewise handled her work.

Beyond the pleasures of “updating” this 17th-century nun, what does it mean for Fabre to bring Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the most famous Latin American poet of the Baroque period, into this monstrous context? The chapbook’s title puts one in mind of such New York Times Bestsellers as Pride and Prejudice and Zombies and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. But, as Pluecker points out in his translator’s note, there is potentially a far more subtle and high-stakes social critique in Fabre’s poems. Fabre has written for such publications as Words Without Borders’ issue on the Mexican Drug War (March 2012), and draws clear parallels between his otherworldly characters and those he wishes to criticize. This is a poet who writes “Zombies: a new opportunity / for the government / to demonstrate its uselessness and corruption” (from “Notes on a Zombie Cataclysm” tr. Amanda Hopkinson).

Thus, as Pluecker writes in his translator’s note, Sor Juana & Other Monsters can be read “in the context of the recent disaster of the PAN-led drug war during the administration of Felipe Calderón…We can let the hundreds of thousands of ghosts of those killed and disappeared during that sexenio into the poems.” Ghosts and monstrous forms of Sor Juana, ghosts and monstrous forms of the killers and the killed throughout the history of Latin America. All in all, this chapbook lives up to its mission to “trouble received ideas around what the terms ‘contemporary’ and ‘Latin America’ might represent.”