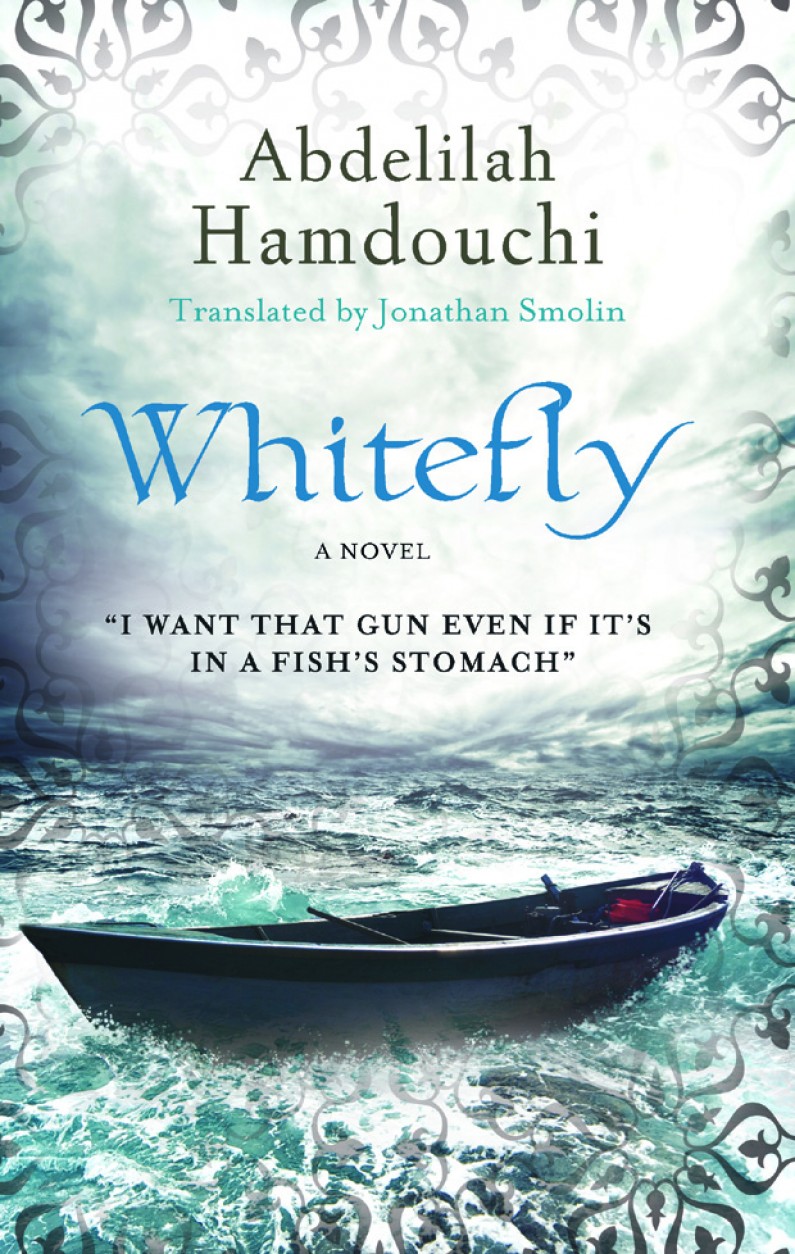

Review: Abdelilah Hamdouchi’s Whitefly

When I was in Morocco last May, I looked forward to evening meals at a restaurant in the heart of Tetouan’s old, winding alleys: chicken with lemon and green olives, or stewed, tender beef with prunes and cardamom, served in a tagine pot. In Abdelilah Hamdouchi’s novel, Whitefly (Hoopoe Imprint, 2016), translated by Jonathon Smolin, a who-done-it set in the contemporary underbelly of Morocco, the victims’ last meal, turns out to be the decisive clue in solving the case. Hamdouchi is known for his detective fiction and screenplays and has written the scripts for seven police thrillers in Morocco. No surprise, then, that his fast-paced novel, full of twists and turns, is an entertaining read, but the text also captures the tragic fate of undocumented Moroccan immigrants who are exploited by those more corrupt and powerful in Spain.

The novel opens when four unidentified bodies wash up on the beach. Stumped, Laafrit asks the coroner to examine the contents of the victims’ last meal. Professor Abdel-Majid, “a solemn man with sallow skin and a crooked back” points out that the last victim is different from the others and believes that the murdered victim is not linked to the other three bodies, who had drowned. He says, “He bid adieu to the world after a tasty meal: salad with extra mayonnaise and seafood paella, topped off with a big piece of chocolate flan for dessert. All this was swimming in more than a liter of wine.…” The drowned men had eaten cheaper street food: vegetables and bread. The medical examiner advises Laafrit to look for a restaurant which serves paella. But where? The bodies still have not been identified.

Laafrit gets his first lead in the case when he visits Fifi, a dancer-turned-informant at the Pyramid nightclub, “a place of real Dionysian pleasure.” The translator has interpreted slightly since the original Arabic is “worldly pleasure”—and the writer does not mention the Greek God, Dionysus. Translators must walk a tight rope between the original text and the cultural understanding of their audience in another language. Hamdouchi’s description of the demimonde in Tangier, and the dancer, Fifi, is ripe in seamy detail; however, the translator opts for idiomatic English, describing how Fifi had “raked in” “three grand”—“a wad of cash.” Hamdouchi, the writer, uses formal words in Arabic, while Smolin has opted for slang in his translation. Smolin might have made these choices to make the story more appealing to the English reader and perhaps he has also been influenced by the tradition of detective fiction in English. Here, is his translation of how Laafrit had “saved” Fifi three years before in a murder investigation:

On that night alone, Fifi had raked in three grand on the dance floor and somehow brought down a millionaire smuggler who insulted her when he told her to pick up a wad of cash ‘with her ass.’ As soon as Fifi’s escort heard that, he pulled a knife and plunged it into the smuggler’s stomach.

When Laafrit realized how much Fifi knew about “dealers, hash barons, and human traffickers,” he decided she would be useful to keep on as an informant. She tips him off that a boat carrying illegal immigrants did get to Spain, except for “three or four who drowned.” Based on her tip, he tracks down a “two-bit smuggler and part-time pimp” named Fouad, who gives him a new clue, which takes him to the coastal city of Martil to a drug dealer’s flat. In the empty flat, they find a Berretta nine-millimeter, which matches the murder weapon of their fourth victim. Next, one of the victims, Driss Al-Yamani from Beni Mellal is identified by his brother. The brother is even more shocked when he realizes the other victims are from his neighborhood. Lafrit also learns that the man who was shot was Mohamed Bensallam, who came back from Spain with a lot of cash, bought a house and got married. In Almeria, he worked on a farm and the owner got him his work papers. The others from the same neighborhood were seduced by the prospect of greater opportunity and they, too, went to Spain on a crowded boat. Jonathon Smolin’s translation evokes the emotion from the original language, when the boy realizes he knows all of the victims:

A strange expression appeared on his face and the shock produced a sharp reaction that rippled throughout his body. His heart beat furiously and the blood drained from his face. Slapping himself on the cheek a number of times, he staggered backward. Laafrit rushed over to Adel-Jalil, telling him he had to calm down. But the kid kept screaming and flailing as if he wanted to hit his head against the wall.

The father of Mohamed Bensallam could not possibly identify his son’s corpse because he is blind. The translator’s sensitive use of English carefully depicts the poignant moment when the father realizes his son is dead:

He made a fist and tucked it into his djellaba pocket. He then raised it up and began rubbing his chest as if to help him digest the disaster. Laafrit thought the old man was trying to express his acceptance of God’s will. But the shock was so powerful that the old man took off his glasses to wipe away his tears. Laafrit moved back. The old man’s eyes were shut completely, but teardrops nonetheless slid down as if they were leaking from above his eyelids.

Smolin sprinkles Arabic words throughout his translation; in this case, using the Berber word, djellaba, seems to work since one might guess such a traditional man would be wearing a wool robe, indigenous to Morocco. The Arabic words do give an exotic flavor to the novel. In a second example, Smolin defines the Arabic word harraga for the English reader, following the word with an explanation: “the people who try to cross illegally.” On the same page, however, he lists Arabic words to refer to Sufi practices: “There are rituals, like dhikr, hadra, amdah.…” In this case, however, the Arabic words, undefined, and without a footnote, would probably confuse a Western reader. A dhikr is a Sufi chanting session; hadra is inspiration from a master; amdah are songs complimenting the prophet, Muhammed. Even students of Arabic, unless they know Moroccan Arabic will not understand amdah since this is a rare plural of madeeh, which means praise. The more commonly used plural is mada’eh, which most Arabic speakers would use.

However, Smolin’s translation of this interview between Laafrit and the old man has the original feel of Arabic without sounding stilted. For example, the old man says, “I haven’t cried in thirty years … There is no power and strength save in God.” Laafrit answers, “May God give you patience, uncle … If you want to postpone our talk, I don’t have any objections.” Inherent in Arabic are constant acknowledgements to the power of God in travelling; in arriving; in health; and in this case, dealing with tragedy.

A good part of the pleasure of reading a detective novel is identifying with the hero, his interior life and the drive to solve the riddle of the crime. The character of Laafrit, the police detective, is likeable and sympathetic. Smolin’s idiomatic translation also adds to the pleasure of reading this novel. Smolin, himself, is no stranger to detective novels. Associate Professor at Dartmouth College, Smolin’s critical work, Moroccan Noir: Police, Crime and Politics in Popular Culture reflects his interest in crime fiction. His other translations include The Final Bet, by Abdelilah Hamdouchi, and A Rare, Blue Bird Flies With Me, by Youssef Fadel, published by the American University in Cairo.

The sympathetic detective, Laafrit understands that the old man is grieving over the death of his son, but he must push forward with his questions if he wants to solve the case. Laafrit learns from the father that his son was coming back frequently from Morocco. The old man feels that the Spanish farmer, Carlos Gomez, his son’s employer was racist, and responsible for his death. Hamdouchi’s honest, hard-boiled detective reminds me of Sam Spade in the Dashiell Hammett’s Maltese Falcon, or Raymond Chandler’s Phillip Marlowe in The Big Sleep with this description:

It was a look that seemed somewhat ambiguous—affected to a certain extent—but what he was known for most these days was his addiction to sucking on menthol lozenges after he’d quit smoking. His real name was Khalid Ibrahim and he got his nickname ‘Laafrit,’ meaning ‘crafty,’ from his professional and linguistic aptitude: he was the only cop in Tangier who spoke Spanish fluently and with a remarkable nimbleness, something that qualified him to work with the Spanish police as part of bilateral cooperation to fight drugs and illegal immigration.

Laafrit decides to follow up on one of the father’s leads by going to Beni Mellal, where he meets Amina, the wife of the victim. He learns that the victim did not spend much time with his bride. And, in a locked drawer he finds a plastic box with vials and a sheet with place names from the Doukkala region. At first, he thinks the vials contain drugs, or an aphrodisiac. Next, he goes to Oualidia and finds the restaurant, the site of Bensallam’s last meal, where a waiter identifies the victim and the owner of the farm, Carlos Gomez. Coincidentally, he meets Si Lahsan, an agricultural engineer who is doing a television show about an insect called whitefly, which spreads a virus dangerous for tomatoes. He also learns Carlos Gomez was the Spanish farmer who had exported his tomato seedlings to Moroccan famers, the previous year.

On his visit to the Doukkala area, Laafrit sees how the tomato crops are destroyed. Despite the Moroccan farmers’ efforts to prevent the virus, the crops have been destroyed a second time. How did the virus come back? Laafrit is now convinced that Bensallam, the victim, is linked to the disaster. He wonders about the vials he has in his possession and asks the agricultural engineer, Si Lahsan, to test the vials—it seems out of character, though, for such a crafty detective to give away every single bit of evidence to someone he does not know.

An old friend, someone Laafrit knows well, Luis, a Spanish detective, fills in the missing pieces of the puzzle. Instead of drugs, the motive for the murder is a monopoly on tomatoes. Carlos Gomez wanted BenSallam’s help to wipe out the Moroccan tomato crop, which would then force Moroccans to buy from the Spanish. Then, BenSallem feels guilty about betraying his country; instead, he decides to turn the tables on Carlos Gomez. He is double-crossed by his three friends, who tell Carlos. Carlos’ sons take the three out on a boat, and dump them into the sea. BenSallam is treated to his last supper at the paella restaurant. When he realizes the game is up, he tries to escape, but Carlos Gomez shoots him at close range.

The novel ends rather abruptly when Laafrit receives a frantic phone call from Si Lahsan’s wife. Maybe following his instincts for the screen too closely, Hamdouchi pared down the tale. He spins a good yarn, and readers would have followed him further, had he gone down more mysterious, dark alleys in Tangier…