Reflecting the Voice of an Iranian Woman Writer in Translation

Translation of classical Persian literature has always been challenging because of the unfamiliar esthetic system; therefore, the translators of contemporary Persian fiction try to choose texts that are nearer to European esthetic norms. Thus, the writers such as Sadegh Hedayat, who made innovations in Persian fiction during the 20th century distanced themselves from the ornamental style of writing in Persian literature, and wrote in a plain style in order to be more universally accessible and translatable (Beard 3-4). Later, female writers such as Simin Daneshvar, contributed to the modernist movement in literature in Iran with her plain and comprehensible style in fiction.

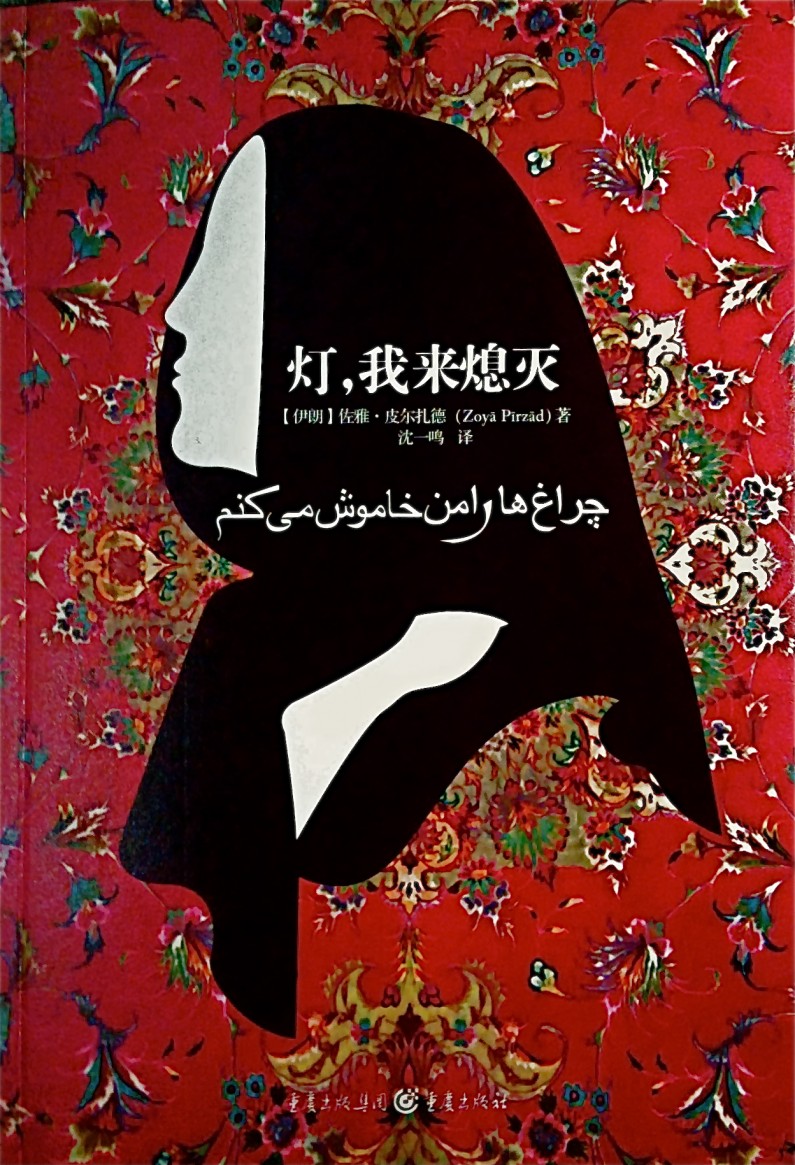

In this essay, using Gayatri Spivak’s postcolonial translation theory, I analyze and discuss the translation of a contemporary woman writer whose novel transcends borders and was translated into several languages including English. Zoya Pirzad, the Iranian-Armenian woman writer, writes from her experience of living in minority in Iran based on her life experience. Her award-winning novel, Cheraghha Ra Man Khamoush Mikonam (I’ll Turn Off the Lights) (2002) that is translated to English under the title of Things We Left Unsaid (2012) by Franklin Lewis, is a story of an Armenian family living as a minority in Iran in the 1960s in the city of Abadan in the South of Iran. The book, according to its author, is “an homage to her birthplace,” and it is “her first novel with tremendous success” (“C’est moi”).

In his book Contemporary Translation Theories, Edwin Gentzler discusses deconstruction and postcolonial translation from Spivak’s point of view. In her essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Spivak questions whether or not the subalterns’ voice under the colonialization process can be heard. She specifically explores how intellectuals reflect the minority’s voice in translation. For Spivak:

…the Western scholar/translator can partially access the subaltern condition, not through what is specifically said by either the subaltern group or by the intellectuals/translators representing them, but by reading that which is not said—reading the gaps, the silence, and the contradictions symptomatically. (Gentzler 183)

Thus, the task of translator is to interpret the oppressed subject in its specific condition. If that subaltern subject is a woman, the text is where she can speak. Therefore, the translator needs to look at the discourse of the colonizer (the patriarchal society) and the codes with which the woman writer has to write. For this reason, Spivak offers a translator’s preface to express the historical and contextual information of the text. In her essay “The Politics of Translation,” Spivak emphasizes that the translator must know the “history of the language, the history of the author’s moment, the history of the language-in-translation” (186). Spivak also asks the translator to guarantee that they are familiar with the “intimate matters in the language in the original” (187).

Based on Spivak’s ideas on translation, I discuss whether Pirzad’s voice can be heard in the translation of her book Things We Left Unsaid. For this purpose, I examine the translated text in terms of the narrator’s feminine language that according to Spivak should be considered by the translator “as a clue to the workings of gendered agency” (179). This means that to what extent the translator focuses on the writer’s attempt to free herself from a stereotypical housewife of the modernizing society of Iran as well as the portrayal of a male dominated discourse in her novel.

Within the scope of this paper, I refer to some examples to clarify the point. In chapter two of the novel, when Claris, the protagonist of the story, who is a housewife and a mother is telling a story for her twin girls at bed time, she uses an expression in Farsi “asemoon rismoon mibaftam” with the literal meaning of I was “sewing the earth to the sky.” This expression is used when you try to get done with a task and have been working hard to get it done. Calris’s goal here is getting her kids to sleep. This expression is very well translated in the context as “I was still sprinkling fairy dust” when they began to fall asleep (Lewis 12). However, in very few cases such as chapter 10, the Persian expression “Posthe Dastamo Dagh Gozashtam” with the literal meaning of “I put fire on the back of my hand” which is used when someone is extremely regretful of what she/he has done, is translated as “I’ll never subject myself to that again,” (Lewis 74) which does not convey the exact meaning of the original expression.

Interestingly enough, the voice of the author can be heard by looking at the cover design and the title. On the most visually observable feature of the book, the cover design of the translation, the name of the writer appears under the title that is located on the center and surrounded by a garden full of birds, flowers, grasshopper, and even small peppers, is in line with the feminine voice of the author. The decision of the publisher to choose a highly symbolic title that is not matching the original title of the book is a strong causality between the author’s voice and the translator’s choice. This illustrates two points, first it informs the reader that the translator is releasing the “unsaid words” of the author which references Spivak’s concept from “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Second, the title invokes the dual nature of the novel, which is not completely written in words, but it is also shaped in the imagination of the reader. The original title of the book, Cheraghha Ra Man Khamoush Mikonam (I’ll Turn off the Lights), is used by the author at many different places in the novel, when at bedtime she tells her husband that she will turn off the lights, even though she is not ready to sleep, because she still has a lot to say and share with her husband who has already fallen asleep. Things We Left Unsaid mirrors the monologue and the inner world of the protagonist who is in dialogue with the reader right from the cover page.

Pirzad’s feminist discourse is very well translated by Lewis, at many places in the novel, such as chapter 11 when there is a speech on “Women and Freedom” by Mrs. Nurollahi, she says “Chizi ke hast in faryadha ba ham naboodeh va dar yek jahat naboodeh va hamagangi nadashteh” which literally means “ the thing is that these cries have not been together, in harmony, and in one direction” (80). This perfectly reflects the voice of the author when it is translated as “ the problem is that their cry has not been united, and has never been coordinated and directed toward a single goal” (80). The choice of the words “united,” “coordinated,” and “single goal” adds to the clarity of the message in this context. Right after this, Mrs. Nurollahi sings a poem that is translated as:

Awake, sister!

In a world where Djamila Boupachas write decrees of

national Freedom

In their own blood across the page of history

Fetching eyes and ruby lips

Are no longer the measure of

Womanhood

(Lewis 81)

In the above poem, Lewis added the last name of the Algerian heroin, Boupachas to his translation. This clarification of the name “Jamileha” in the original text, which literally refers to the plural form of the female name “Jamileh” and could be confusing even for the native reader, to Djamila Boupachas, signifies his mastery of decoding the author’s unsaid words. Second, in the same poem, the translator changes the phrase “Tanha sharte zan boodan nist,” which literally means “it is not the only reason to be woman,” into “ Are no longer the measure of Womanhood.” This change is another indication of the translator’s ability to reflect the hidden voice of the author, which refers to the awareness that feminist writers have brought to modern literature in Iran, which means that Iranian women are no longer objectified and colonialized by the dominant patriarchal system.

Finally, Spivak recommends that the translator include a preface to represent the historical, linguistic, and cultural background of the text. While the translator does not include a preface or introduction, which could perfectly guide the reader to the historical and cultural background of the novel as well as familiarity with the translator and his sufficient knowledge of the language and culture of Iran, he includes a glossary that well informs the reader of all the names of people, places, and foods that are used in the translation.

In sum, Things We Left Unsaid with its fresh and clear narrative in English echoes the voice of its author to the world. Perhaps the translator, a globally famous figure in Persian literature and translation in the US and the Middle East, chose to translate Cheraghha Ra Man Khamoush Mikonam (I’ll Turn off the Lights) for this specific reason. Perhaps Lewis wanted to say “the unsaid” by an Armenian/Iranian-American female who has lived in the minority. Pirzad is among those rare authors who has lived her life in minority, her protagonist Claris, is also an Armenian housewife living in Iran in minority, not only because of her religion, but also Claris suffers from a deep sense of melancholy because of her surroundings. Claris is the perfect character to symbolize the life of an ordinary modern woman of the minority in Iran.

Beard, Michael. “ENGLISH iv. Translations Of Modern Persian Literature.” Encyclopedia Iranica. Encyclopedia Iranica, 15 Dec. 1998. Web. 23 Jul. 2016.

Gentzler, Edwin. Contemporary Translation Theories. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 2001. Print.

Guha, Ranajit, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, eds. Selected Subaltern Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988. Print.

Haddadian-Moghaddam, Esmaeil. Literary Translation in Modern Iran. Vol. 114. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2015. Print.

Pirzad, Zoya. Cheragh-ha-ra Man Khamoosh Mikonam (Things We Left Unsaid). Tehran: Nashr-e Markaz, 2002. Print.

—. Things We Left Unsaid. London: Oneworld Publication, 2013. Print.

—. “C'est moi qui éteins les lumières.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 22 Jul. 2011. Web. 24 Jul. 2016.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. Outside in the Teaching Machine. New York: Routledge. 1993. Print.