“The unwritten which is sacred”

On Translating the Novena to Our Lady of Mt. Carmel from Early Modern Binisaya

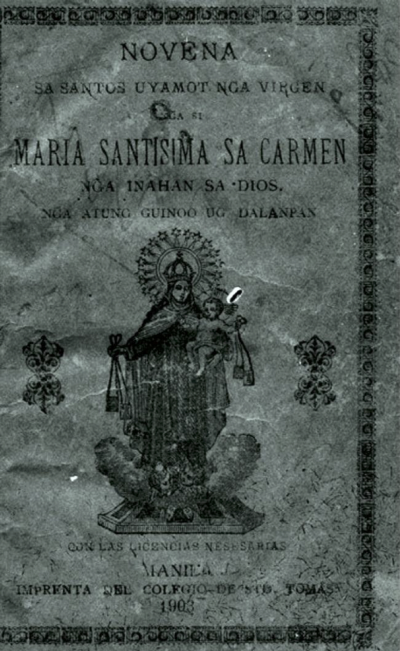

Manila, Philippines: Imprenta del Colegio de Santo Tomas, 1903

Image courtesy of the Northern Illinois University Southeast Asia Digital Library

Novenas are prayer rituals done in public (at the church with the community, outside the house with the neighbours) or in private (in the living room with the family or alone in one’s bedroom). On both occasions, people kneel before and face an altar embellished with statues and icons of saints. From the Latin novem, “nine,” a novena involves continuous praying for nine consecutive times, either in nine consecutive days or once a week for nine consecutive weeks, to signify the nine days the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Apostles waited for the coming of the Holy Spirit between the Ascension of Jesus Christ into heaven and the Pentecost. Historically, a number of these novenas were reprinted and translated in Latin America and the Philippines starting in the mid-1700s, although novenas for special feasts and graces have been traced back to the early Middle Ages.1 But is the novena the performance of the prayer or is it the prayer-as-text? The answer lies in between both.

George Steiner, in his foreword to Translating Religious Texts (1993), explains: “Even more than lyric and epic poetry, religious texts are rooted in orality. The first, and in many cultures insuperable, transgression—where ‘transgression’ is itself a motion of transport, of translation—is that which crosses the line between oral and written.”2 As a kid who came of age in the Christian settler-dominated northern region of post-Hispanic southern Philippines, I grew up reciting some of these novenas, mindlessly for the most part, with the adults on different occasions, e.g. to pray for a cousin who was about to take a licensure examination or for the soul of a great-grandparent who recently passed. During the nightly vigils for the dead, the novena is led by a manalabtan, usually an old woman who has had to traverse mountains and rivers to get to the house where the dead body is laid for a few nights before the funeral. There, she recites the prayers from memory in vocal gymnastics, reminiscent of the chanters and bards of our pre-Hispanic epic poetry, or of the babaylan, precolonial warrior-priestesses serving various socioreligious functions.3 While I remember reading old booklets containing these novenas, I also distinctly recollect some people being able to recite these hour-long prayers, beginning until end, without a visual aid. As Steiner asserts, the religious text, once transcribed, becomes “part of a general and impure textuality, subject to amendment and circumstantial revision. It is the unwritten which is sacred.”4

In general, novenas serve as one of the many ways to venerate and seek help and guidance from specific patron saints. It is, first and foremost, a “para-liturgical” appeal for saintly intercession condensed as “private or public vernacular prayers.”5 A person who wishes that their work visa be approved for an overseas job, for instance, might choose to perform a novena to St. Lorenzo Ruiz, the patron saint of migrants, while someone who is undergoing chemotherapy may recite a novena to the “cancer saint,” St. Peregrine Laziosi. Other novenas are very specific: an 1817 novena to St. Boniface of Tarsus written by José Manuel del Valle y Araujo, priest of an archdiocese in colonial Mexico, was specifically for those considered sexually promiscuous, with the stated aim of “obtaining from God the deliverance of those poor individuals who… are in the mortal sin of inhuman vice.”6 Prefaces to these novenas served as prototypes of the modern Philippine essay in the local languages, a genre which according to the Encyclopedia of Philippine Art “was developed for religious purposes.”7

In the case of the text that is the focus of this essay, the Novena to Our Lady of Mt. Carmel begins with a proclamation of the saint’s immense power as a universal knowledge among Christians: “Oalay caistianos nḡa dili masayod nḡa ang paglaban ni Maria nḡa santos uyamot, mao ang usá ca tambal ug alaguian nḡa macagagahom caayo.” Named after a mountain range in the northwestern part of historic Palestine (according to the pre-1947 UN Partition Plan), Our Lady of Mount Carmel, or the Virgin of Mt. Carmel, is the patron saint of those who wish protection from harm and dangerous situations and deliverance from purgatory, as illustrated in the following excerpt from the novena’s second prayer recited on the first day:

PAG-AMPO NGA ICADUHA

¡O Virgen Maria! nga Inahan sa Dios ug sa mga macasasala, ulusahon nḡa manlalaban sa mḡa tauo nḡa nanagvisti sa sagrado mong Escapulario: tunḡod cay guipataas icao sa Dios, sa pagpili canimo adon mahimo ca ug Inahan nia nḡa matuod, manḡamuyo acó canimo nḡa icuha mo acó sa hinigugma mong Anac, nga si Jesus, sa pagpasaylo sa mḡa sala co, sa pagtapat sa dili na pagbalic sa quinabuhi cong daan, sa mḡa pagtabang sa acong quinahanglan nḡa tanan, sa calipay sa mga casubó ug mga cayogot co, sa pagcabutang sa gracia sa calág co, ug sa guipanḡayo co, nḡa labi, niining novena; ug dao nḡa omangay sa labing dagco nḡa donḡog ug paghimaya nia, ug sa ca-ayo sa calág co, cay acó, Señora, mudanḡop canimo, adon domanḡat acó niana, ug sa macagagahom nḡa paglaban mo; ug buot acó unta nḡa pagapuy-an acó sa Espiritu sa mḡa Angeles, sa mḡa Santos ug sa mḡa matadong nḡa tanan sa pagdayeg canimo inḡon sa anḡay: busa ilaquip co ang acong tinḡog sa mḡa paghigugma nila, ug magaolog acó canimo sa macausa ug sa macausa ca libo sa pagpamolong.

SECOND PRAYER

O Virgin Mary, Mother of God and of sinners, lone protector of the people clothed in thy sacred Scapular: because thou are exalted by God, chosen to be his true Mother, I beseech thee to deliver me to thy beloved Son, Jesus, to forgive my sins, with the promise that I never return to my old ways, to help me with everything that I need, in abundance and in anguish and in anger, to wear thy grace unto my soul, and to my wishes, especially in this novena; and to be worthy for His honour and glory, and for the goodness of my soul, for I, oh, Our Lady, come unto thee, that I may deserve that and thy mighty defense; and I desire that the Spirit of the Angels, of the Saints, and of all the righteous dwell in me, to praise thee as thou should be: therefore I will append in this prayer my love for them, and I will praise thee once and in a thousand words.

How ingrained is the Our Lady of Mount Carmel in the Filipino Catholic imaginary? Several places in the Philippines are named after her, including the largest suburban barangay, or village, in the city that is my hometown, and the second most populous coastal town in the island where I moved in; each has at least one chapel of the same name. (A quick Google Maps search reveals at least three Our Lady of Mount Carmel churches near my current location as I write this essay.) I am no stranger to the rituals still being practiced every July 16th, the patron saint’s designated fiesta in the Catholic calendar. This coloniser legacy of poblaciones, townships, centered on churches (and on the church bells in particular), is founded on reducción, the relocating of the indios, natives, by force or collective gaslighting and manipulative propaganda, as the distance between their houses—sometimes mountains away from one another—became a hindrance against indoctrinating them towards Catholic Christianity and thus, imperial expansion.8

The study on the field-formation of colonial and popular devotional literature is nothing new in Filipino scholarship, as these literary forms have already been scrutinised under the lenses of literary history (see Resil B Mojares9), historiography (see Reynaldo Ileto10), cultural translation (see Vicente L Rafael11), and stylistics (see the work of Cyril Belvis), thus already laying important groundwork for this essay. After all, as Norlan H Julia has pointed out, “affiliation to popular religiosity” remains deeply embedded in the national psyche; Filipinos in the diaspora are no exception to this, especially in their devotion towards Saint Mary.12 In the present-day Philippines, this manifests as what Mark R Francis terms as “devotional Catholicism” in the form of “processions, pilgrimages, rosaries, novenas, wearing holy medals and scapulars, veneration of relics, and other special local customs developed alongside the official liturgy of the church.”13

In translating the present text from the archives of Northern Illinois University’s Southeast Asia Digital Library, I assert that novenas, already characterised by what Mojares calls “hybridity in textual and visual representation” and “semantic instability,”14 borrow their thematic religiosity from a tradition of Spanish religious poetry, both lyric and (mostly didactic) narrative in the former Hispanophone colony, and their tonal solemnity from the harito, prayers of the babaylan and other spiritual mediums addressed to particular deities to ask for blessings of harvest and abundance, or “invocations to environmental spirits or animals believed to possess powers.”15 Although categorised by literary historians as a lyric rather than narrative genre, I think of the novena, and especially of the present text, as a delineation between the lyric meditative verse and prose narrative as it actually tells a story, illustrative of the hybridity of folk Christianity and symptomatic of the performative modes characteristic of secular interludes, morality plays, and liturgical drama. “Hybrid in their composition,” Deirdre de la Cruz writes of the similar genre of devocionarios, “[they] draw awkwardly and elegantly from both traditional modes of versification … and the standard repertoire of Christian prayer.”16

A dimension in translating these religio-literary texts is what David Jasper calls their “peculiar difficulty and elusiveness”17 on the textual level, and beyond that the fact that historically translations of such texts have “inevitably assumed religious significance: the resulting translation [being] seen as a transparent representation of a semantic invariant, divine meaning.”18 While I intend nothing like that here, translating the novena has its own challenges. When I tried to compare these same novenas with the English versions available, I found that they differ in content. Why? Speaking about cultural translation as one of the strategies used against the Tupi people in the 16th century, Paulo Edson Alves Filho and John Milton make the comparison to the early Franciscan settlers in Mexico, whose

“...strategy [in] trying to convince them of the superiority of the Christian God and thus the need to have the natives converted to Catholicism, was that of using the thinking system of the natives and operating in the logic of the Other (the Aztecs in this case) in order to convert them, as a “natural” consequence of their own way of thinking.”19

The Spanish colonisation was indeed two-fold: a “territorial conquest and a spiritual mission,”20 or—as Mojares posits—“religious instruction and ideological control.”21 I theorise that novenas like this, in themselves tools for indios to be indoctrinated with the teachings of the Church and catechised into Catholicism, would not be considered “faithful” translations of the originals from Rome or Madrid or Lisbon, and may have no exact textual equivalent in other postcolonies of Hispanophone and Lusophone spheres spanning Latin America, Africa, Oceania, and other parts of Asia. In Oceania, for instance, Joseph P. Hong remarks on the Christian missionaries’

“…deep-seated pre-occupation with producing a text that was meaningful and sounded natural to the Pacific islanders, while at the same time the pull towards literalness was irresistible because it involved a religious text perceived as sacred and unchangeable. Ultimately, the purpose was to win the readers’ heart and mind and their conversion to the Christian faith...”22

In the Philippines (as elsewhere in the then-Spanish Empire and, possibly, Catholic colonies), friars deliberately privileged indigenised content—which explains the successful indoctrination into the collective Filipino consciousness beginning in the 17th century—over doctrinal and scriptural accuracy. It was, after all, a Spanish friar who published the first study of poetic forms of the Binisaya language. But de la Cruz further points out a certain tug-of-war between the literal and the localised: “With their references to faraway places, moralistic or religious messages, and florid verse or prose, these novenas presented, to a degree, a spatiotemporal universe unmoored from any actual context in which indio or mestizo readers might find themselves or understand as actually existing elsewhere.”23 The solution, for the friars in particular and the Catholic Church in general, was the highlighting of what is relevant to a given audience. In the passages below, noticeable is the emphasis on landscapes: the Philippines, being of the tropics, having rainy and dry seasons, and the islandic Cebu province, being the seat of the Cebuano Binisaya language where this novena has been written in (or, presumably, translated into from the Latin), abundant with imagery of mountains and valleys.

PAG-AMPO NGA ICATOLO

¡Oh Virgen sa Carmen, María nḡa santos uyamot! nḡa guildaoanan ca nianang diotay nḡa panganod nḡa guiquita sa dagcong manalagna sa Dios, nḡa si Elias, nḡa nagama ug miguican sa dagat, nḡa nagapabonḡa ug maayo sa yuta sa ulan nḡa guiyagyag nia, nḡa maoy hinḡtungdan ug cahulugan sa ulay nḡa pagbunḡa sa tian mo, sa paghatag mo sa calibutan sa hinigugma nḡa Anac mo nḡa si Jesús, nḡa tambal nḡa macaayo sa mḡa casaquit nḡatanan sa among mḡa calág: tunḡod niini, naḡaampo acó canimo, Señora, nḡa icuha mo acó, sa pagcahalangdon nia, sa daghan nḡa mḡa ulan sa pagtabang adon mubonḡa ang calág co sa mḡa bonḡa, nḡa daghan usab uyamot, sa mḡa virtudes ug sa mḡa buhat usab nḡa maayo, nḡa icasilvi co cania niining quinabuhi, adon mahimo acó ug tacús sa paghiagom cania sa quinabuhing dayon sa Langit, ug adon macadanḡat acó cadon sa guipanḡayo co, nḡa labi, niining novena, sa alaguian sa imong paglaban; busa naḡaampo acó canimo, Señora, sa dagcong pagpaobos, sa pagpamolong:

(Cadon papanḡadyeon ug usá ca Maghimaya ca Hadi; ug sa natapus na, pangadyeon usab ang letania, nḡa pagasumpayan sa sonod sa Regina Virginom, niining mga polong: Regina Carmelitarum.)

THIRD PRAYER

Oh, Virgin of Carmel, Blessed Virgin Mary, with emblems of the low clouds witnessed by God’s great prophet, Elijah, built and born of the sea, revealing the good fruit bore from the land of rain, the reason and meaning of the fruit of thy virgin womb, when thou give to the world Jesus, thy beloved Son, the cure of all cures of the pains of our souls: for this, I pray to thee, Our Lady, to deliver me, in His majesty, and the countless rains so that my soul will bear fruit, abundant both in word and in work, that I may serve Him in this life, that I may be worthy to suffer for Him in the eternal life in Heaven, and that I may now obtain what I have asked, especially in this novena, with thy defense; therefore I pray to thee, O Lord, in great humility, to say:

(Now pray one Hail Holy Queen; and at the end, the litany and the Regina Virginum, in these words: Regina Carmelitarum.)

Or consider these verses excerpted from the “Gozos con mga Pagdayeg” [Joys and Praises], acting as both adoration and supplication types of Catholic prayer:

Bato balani nga catingalahan,

Ug sa cacugui namo nḡa dalangpan.

Sa buquid nḡa Carmelo panḡanod ca,

Cami nḡatanan imong paglabanan.

…

Itungha mo canamu ang anac mo

Ni Josafat sa oalog nga dagcó,

Nḡa punó sa calooy, cay natauo

Sa salamin sa pagcavirgen nimo.

Sa buquid nḡa Carmelo panḡanod ca,

Cami nḡatanan imong paglabanan.

Lodestone of such marvel,

And in our zeal is the refuge.

Beyond the pinnacle of Carmel, you lord over,

All of us, under your providence

…

Show before us your son

In this great valley of Jehoshaphat,

Overflowing of charity, conceived

In the likeness of your purity.

Beyond the pinnacle of Carmel, you lord over,

All of us, under your providence.

Another challenge, apart from trying to capture what poet and Binisaya-to-English/English-to-Binisaya translator Marjorie Evasco might call the “musical body” of the original work (the Binisaya language being polysyllabic most of the time, written and spoken, formal and informal), was in trying to decipher the archaic, early 20th-century orthography (spelling, diction, punctuation) used in this text. As the Binisaya language doesn’t have a sanctioned modern orthography even today, I cross-referenced the lexicon with multiple sources: reference grammars Fr Gregorio de Santiago’s Mga Paquigpulong sa Iningles ug Binisaya (Imprenta de Santos y Bernal, 1905) and Fr Manuel Yap’s Ang Dila Natong Bisayá (Star Press, 1947); dictionaries Fr Juan Félix de la Encarnación’s Diccionario Bisaya-Español (1885), Alton L Hall’s Dicsionario Bisaya-Inggles (1911), John U Wolff’s A Dictionary of Cebuano Visayan (Cornell University-Southeast Asia Program/Linguistic Society of the Philippines, 1972), and Rodolfo Cabonce’s An English-Cebuano Visayan Dictionary (National Book Store, 1983); and Elsa Paula Yap and Maria Victoria R Bunye’s book series under the University of Hawaii Press (1971): Cebuano-Visayan Dictionary and Cebuano Grammar Notes.

Works Cited

1 David A Gilbert, “The Novena to St. Boniface of Tarsus: A Pastoral Program for Addressing Sexual Addiction in Colonial Mexico,” Catholic Social Science Review 19 (2014): 88.

2 George Steiner, “Foreword,” in Translating Religious Texts: Translation, Transgression and Interpretation, ed. David Jasper (Macmillan, 1993): xii.

3 For more on the babaylan, see Grace Nono, Babaylan Sing Back: Philippine Shamans and Voice, Gender, and Place (Cornell University Press, 2021).

4 Steiner, xii.

5 Gilbert, 88.

6 Gilbert, 104.

7 Rosario Cruz Lucero, “Essay,” in Encyclopedia of Philippine Art (Cultural Center for the Philippines, 1994): 141. An essayistic genre called pagninilay or omameng of the Tagalog, for example, is a discussion that reflects and meditates which precedes the novena’s didactic narratives. The themes of the said discussions could range from “grace, love of God, or the fires of hell.”

8 Jared Koller and Stephen Acabado, “Under the Church Bell: Reducción and Control in Spanish Philippines.” Presented at The 82nd Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Washington DC. 2018.

9 Resil B Mojares. Origins and Rise of the Filipino Novel: A Generic Study of the Novel Until 1940. University of the Philippines Press. 1998 [2020].

10 Reynaldo Clemena Ileto, Pasyon and Revolution: Popular Movements in the Philippines 1840–1910. Ateneo de Manila University Press. 1979.

11 Vicente L Rafael, Contracting Colonialism: Translation and Christian Conversion in Tagalog Society under Early Spanish Rule. Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1988 [2011, co-published with Cornell University Press].

12 Norlan H Julia, “Popular Piety in Migrant Journeys toward Redemption,” in Catholicism in Migration and Diaspora: Cross-Border Filipino Perspectives, ed. Gemma Tulud Cruz (Routledge, 2022).

13 Mark R Francis, “Church Life in the First Half of the Twentieth Century,” in The Cambridge Companion to Vatican II, ed. Richard R. Gaillardetz (Cambridge University Press, 2020): 13.

14 Resil B Mojares “Stalking the Virgin: The Geneaology of the Cebuano Virgin of Guadalupe.” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 30, no. 1/2 (2002): 138–71.

15 Damiana Eugenio, Edgar Maranan, and Rosario Cruz Lucero, “Folk Poetry,” in Encyclopedia of Philippine Art (Cultural Center for the Philippines, 1994): 178. The harito, a poetic form indigenous to the Cebuano Binisaya-speaking indios, is an equivalent to the Tagalog bulong and the Kinaray-a tara. Other permutations came in the form of thanksgiving (the Ilonggo ambaamba), entreaty (the Kalinga tubag, the Aeta magablon), exorcism (the Ilonggo bungyaw), appeal for good harvest (the Ilonggo dag-unan), among other prayers on healing and pleas.

16 Deirdre de la Cruz, Mother Figured: Marian Apparitions and the Making of a Filipino Universal (University of Chicago Press, 2015): 29. A good example of this hybridity in practice is shown in Ronald K Edgerton’s 1983 case studies of the Rizalista movement and its religious practices; see Ronald K Edgerton, “Social disintegration on a contemporary Philippine frontier: The case of Bukidnon, Mindanao,” Journal of Contemporary Asia, 13:2 (1983): 151-175.

17 David Jasper, “Introduction: the Painful Business of Bridging the Gaps,” in Translating Religious Texts: Translation, Transgression and Interpretation (Macmillan, 1993): 1.

18 Lawrence Venuti, “Foundational Statements,” in The Translation Studies Reader (4th ed.) (Routledge, 2021): 15.

19 Paulo Edson Alves Filho and John Milton, “Inculturation and acculturation in the translation of religious texts: The translations of Jesuit priest José de Anchieta into Tupi in 16th century Brazil,” Target 17:2 (2005): 276.

20 Alves Filho and Milton, 278.

21 Resil B Mojares, “From Cebuano/To Cebuano: The Politics of Literary Translation,” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, 18:2 (June 1990): 75.

22 Joseph Hong, “Translating in the Pacific: Rendering the Christian Bible in the islanders’ tongues,” in World Atlas of Translation, eds. Yves Gambier & Ubaldo Stecconi (John Benjamins, 2019): 35.

23 de la Cruz, 52.