On Asparagus:

We have spears with crooked ends

that stand tall and proud

With most agreeable sleek shafts

and heads that crown their stalks,

In form like soldiers, bold and stout,

in posture straight like sturdy staffs,

Clothed in raiment of green sarcenet

inwrought with a flaming blush,

Like a tinted cheek flushed

by an irritated hand

Or a hand turned red

in a silver bowl filled with ice,

Elegantly arranged on platters

like neat embroidered goldwork

Adorning the hemline of the finest silk –

o if only we had a bottomless well!

They are dressed with an oily relish

that ebbs and tides like seafoam

When drizzled onto the stalks

like nets of cast silver and gold

And pearl rings with gemstones adorned,

adding beauty to their beauteous form.

A sedulous ascetic would break his fast

and yield before such a repast.

On Mushabbak:

A most agreeable food

that brings about joyful glee

Is plaid and knit sweetmeat

oozing with honey

Laid out on silver platters,

yielding before me

Like joined cross-bars of gold

scented with amber and camphor tree.

On Khushkanānaj:

Lo, as powdered sugar,

pounded soft almonds,

And semolina are kneaded together

with musk-sweet rose water,

Crimped, rolled, and stuffed

with every scrumptious foodstuff,

And shaped like a string of crescents

rising in timely succession before sunrise.

Never in my life have I seen Khushkanānaj

that fell short of gratifying the senses.

Whose heart does not long for it?

Whose hands are not enticed by it?

It would be discourteous if you ever were

to deny me my share,

For my mouth cannot help but water

whenever I hear its name.

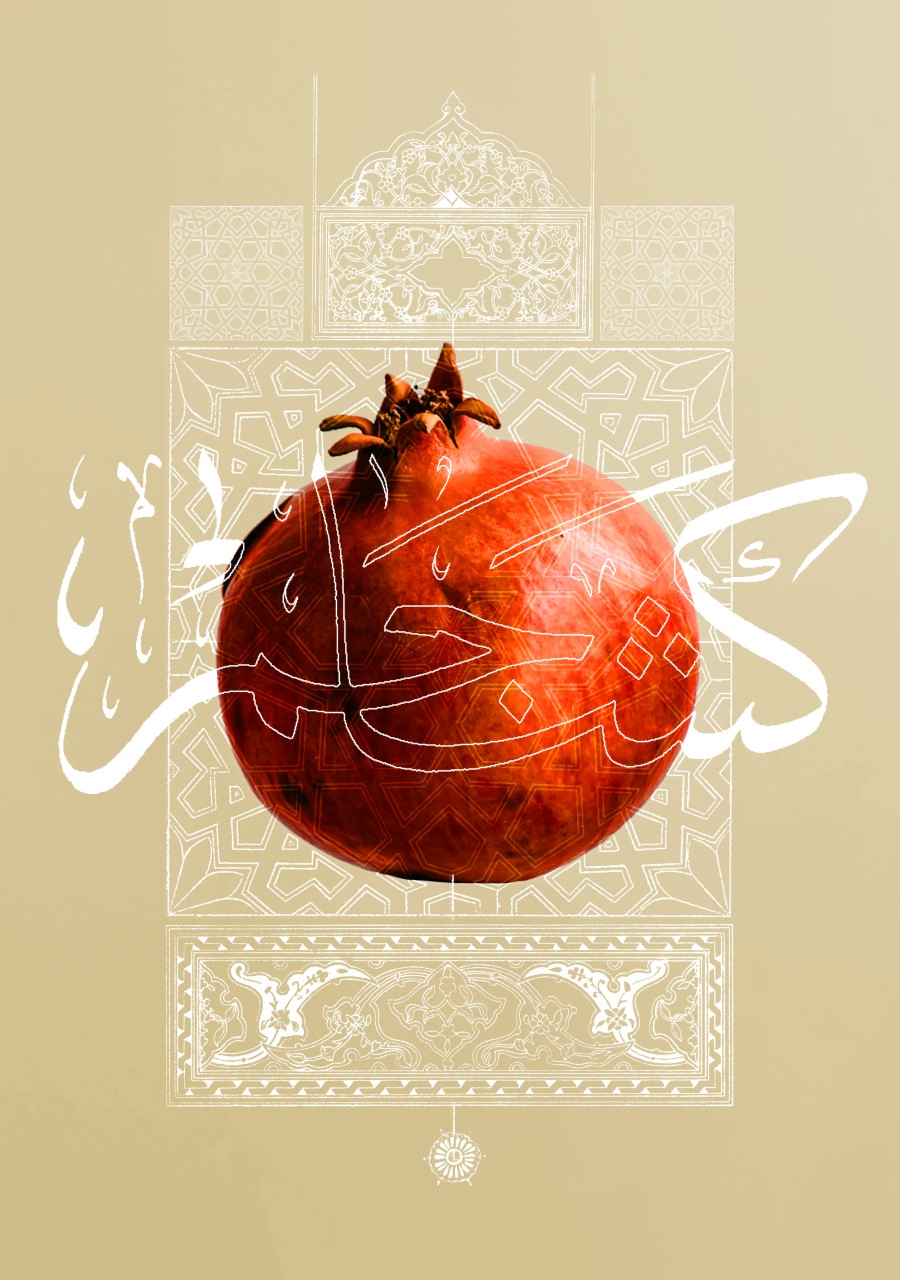

On Pomegranates:

The pomegranates’ beauteous forms appeared,

some whole, some cleft pouring forth

With seeds in yellow and saffron-red hues

in beauty that surpasses all attributes,

Like glistening rubies safely casketed

in an ivoried jewelry box.

عن الهليون:

لَنَا رِمَاحٌ فِي أَعَالِيْهَا أَوَدْ مُفَتَّلَاتُ الْجِسْمِ فَتْلًا كَالْمَسَدْ

مُسْتَحْسَنَاتٌ لَيْسَ فِيْهَا مِنْ عُقَدْ لَهَا رُؤُوسٌ طَالِعَاتٌ فِي جَسَدْ

مَكْسُوَّةٌ مِنْ صَنْعَةِ الْفَرْدِ الصَّمَدْ مُنْتَصِبَاتٌ كَالْقِدَاحِ فِي الْعُمُدْ

ثَوْبٌ مِنَ السُّنْدُسِ مِنْ فَوْقِ جَسَدْ قَدْ أُشْرِبَتْ حُمْرَةَ لَوْنٍ يَتَّقِدْ

كَأَنَّهَا مَمْزُوجَةً حُمْرَةُ خَدْ قَدْ فَرَصَتْ حُمْرَتَهُ كَفٌّ حَرَدْ

فَخَالَطَتْهُ حُمْرَةُ خَدٍّ وَيَدْ كَأَنَّهَا فِي صَحْنِ جَامٍ أَوْ بَرَدْ

مُنَضَّدَاتٌ كَتَنَاضِيْدِ الزَّرَدْ نَسَائِجُ الْعَسْجَدِ حُسْنًا مُنْتَضَدْ

كَأَنَّهَا مُطْرَفُ خَزٍّ قَدْ مَهَدْ لَوْ أَنَّهَا تَبْقَى عَلَى طُولِ الْأَبَدْ

كَانَتْ فُصُوصًا لِخَواتِيْمِ الْخُرَدْ مِنْ فَوْقِهَا مَزْىٌ عَلَيْهَا يَطَّرِدْ

يَجُولُ فِي جَانِبِهَا جَزْرٌ وَمَدْ مَكْسُوَّةً مِنْ زَيْتِهَا ثَوْبَ زَبَدْ

كَأَنَّهُ مِنْ فَوْقِهِ حِيْنَ لَبَدْ شِرَاكُ تِبْرٍ أَوْ لُجَيْنٍ قَدْ مَسَدْ

فَلَوْ رَآهَا عَابِدٌ أَوْ مُجْتَهِدْ أَفْطَرَ مِمَّا يَشْتَهِيْهَا وَسَجَدْ

عن المشبك:

أَطْيَبُ مَا نِلْتُ مِنَ الَّلذَّاتِ وَمِنْ سُرُورٍ مُعْجِبِ الْأَوْقَاتِ

مُشَبَّكَاتٌ وَمُفَصَّلَاتٌ فِي عَسَلِ النَّحْلِ مُشَرَّبَاتِ

كَأَنَّ مَا صُفِّفَ فِي الْجَامَاتِ إِذَا تَرَاءَتْ لِيَ مَاثِلاَتِ

قُضْبَانُ تِبْرٍ مُتَرَاكِبَاتِ مُعَنْبَرَاتٍ وَمُكَفَّرَاتِ

عن الخُشْكِنَانِكَ:

مَنْ لِذَاكَ الطَّبَرْزَذِ الْمَسْحُوقِ وَلِذَاكَ اللَّوْزِ الطَّرِي الْمَدْقُوقِ

وَدَقِيْقُ السَّمْيِذِ يُعْجَنُ بِالْمَا وَرْدِ عُلِّى بِمِسْكِهِ الْمَسْحُوقِ

ضُمَّ أَجْزَاؤُهُ وَأُلِّفَ أَجْسَامًا حَوَتْ كُلَّ مَطْعَمٍ مَوْمُوقِ

ثُمَّ صَفُّوهُ كَالأَهِلَّةِ لاَحَتْ لِمَوَاقِيْتِهَا حِيَالَ الشُّرُوقِ

مَا رَأَيْنَا كَخُشْكِنَانِكَكَ الْمَوْصُوفِ رَعْيًا لِحَقِّهِ فِي الْحُقُوقِ

أَيُّ قَلْبٍ إِلَيْهِ غَيْرُ مَشُوقٍ أَيُّ طَرْفٍ إِلَيْهِ غَيْرُ عَلُوقِ

غِبْتَ عَنِّي فَغَابَ عَنِّي نَصِيْبِي أَنْتَ عِنْدِي بِذَاكَ غَيْرُ خَلِيْقِ

لِيْسَ لِي مِنْهُ غَيْرَ أَنِّي إِذَا مَا عَنَّ لِي ذِكْرُهُ أَغَصُّ بِرِيْقِي

عن الرمان:

وَلَاحَ رُمَّانُنَا فَزَيَّنَنَا بَيْنَ صَحِيْحٍ وَبَيْنَ مَفْتُوتِ

مِنْ كُلِّ مُصْفَرَّةٍ مُزَعْفَرَةٍ تَفُوقُ فِي الْحُسْنِ كُلَّ مَنْعُوتِ

كَأَنَّهَا حُقَّةٌ فَإِنْ فُتِحَتْ فَصُرَّةٌ مِنْ فُصُوصِ يَاقُوتِ

Artwork by Hassân Al Mohtasib