The Poetry of Survival

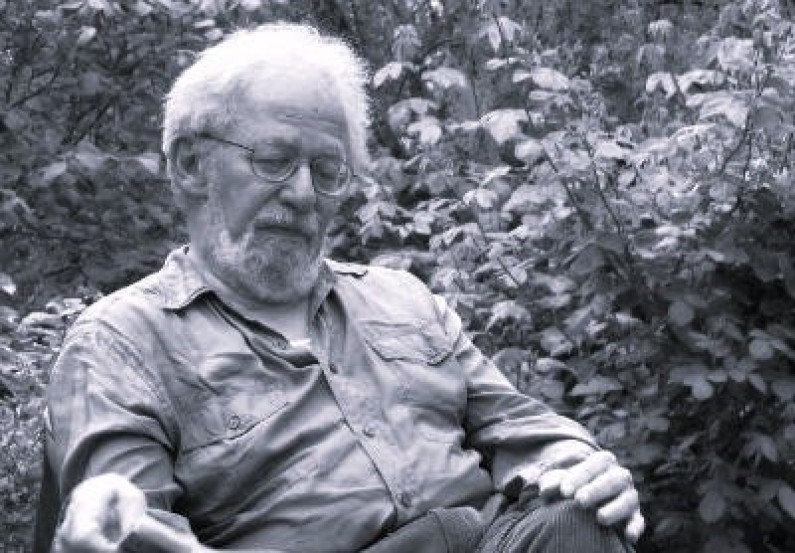

A tribute to Daniel Weissbort—a gentle man in a violent world.

By Michael Judge

This article originally appeared in The First Person with Michael Judge, the former WSJ editor’s independent newsletter featuring conversations with—and essays by—writers, thinkers, and doers around the globe.

we’re not comfortably at home

in our translated world . . .

—Rainer Maria Rilke Duino Elegies (trans. A. Poulin, Jr.)

So we have war. Calls for peace. Protests. More war and speeches about the “barbarism” of our enemies. Like King Nimrod’s ancients in the land of Shinar crawling from the rubble of the Tower of Babel, words seem powerless to salve the wounds or prevent still more death and destruction.

Some of us turn to contemplative silence, prayer, poetry. Yet even poetry can seem obscene—a vain and useless sacrilege—at times like this. The German philosopher Theodor W. Adorno famously proclaimed, “to write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric.”

Adorno was and is wrong. The world needs what’s at the heart of poetry—witness, warmth, humanity, grief, resistance, regret, rage, silliness, solemness, ritual, music, awkwardness, irreverence, wonder—more than ever.

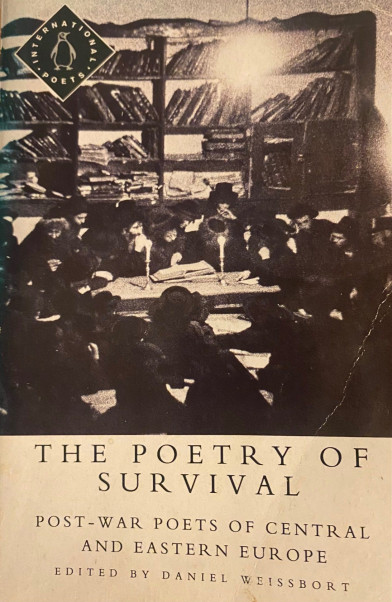

No one, I believe, understood this more inherently than my teacher and mentor, Daniel Weissbort, co-founder with Ted Hughes of the landmark Modern Poetry in Translation, professor of comparative literature and director of the groundbreaking University of Iowa Translation Workshop, and editor of one of the most important anthologies—if not books—of the 20th century: The Poetry of Survival: Post-War Poets of Central and Eastern Europe.

First published in 1991, The Poetry of Survival brings together, for the first time in translation, such postwar greats as Yehuda Amichai, Bertol Brecht, Zbigniew Herbert, Miroslav Holub, Czesław Miłosz, Ágnes Nemes Nagy, János Pilinszky, Vasko Popa, Tadeusz Rózewicz, Nelly Sachs, Leopold Staff, Anna Swirszczynska, and Wislawa Szymborska, who was later awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize in Literature.

In his introduction, Weissbort addresses Adorno and “the impulse to keep silent, if only for fear of traducing or reducing the experience, denying or aestheticizing it, betraying the ‘millions of the mouthless dead,’ to borrow a particularly appropriate image from a First World War poem.” Yet a “contrary impulse” also exists—the impulse “to bear witness, to ensure that the silence which engulfed those millions does not consume also the survivors. This is, perhaps, what it means to survive. To say nothing may, in effect, be to collude with the forces of destruction.”

This phrase, it seems to me, defined Danny’s career as a translator, teacher, and poet himself—his lifelong commitment to never “collude with the forces of destruction.” I suppose that’s why I haven’t been able to get Danny, who died in 2013 at the age of 78, out of my mind since the Oct. 7 massacre in southern Israel and the ensuing war that now looks as if it may engulf the region, if not the world.

Danny was born in London in 1935. His parents, Maurice and Rachelle, were Polish Jews who arrived in Britain in the 1930s via Belgium. As his obituary in the Guardian explained, “In the house they spoke French together, the language of their first acquaintance, but Danny remembered answering them in English.” This multilingual reality, he explained many years later, was central to his identity. “Writing poetry, for me, is trying to find a language I lost before birth,” he said. “This is an obscure enterprise, to say the least, and I have discovered few guides.”

Danny, always the gentleman, soft-spoken and self-effacing almost to a fault, described his approach to translation as a “way of reading,” and his poetry writing as “indispensable to listening rather than the other way round.” Yet he translated or co-translated more than 20 books of poetry, edited eight anthologies, and published 12 collections of his own poetry, including Letters to Ted (2002), poems in memory of his dear friend and co-MPT founder, the poet Ted Hughes; and From Russian with Love (2004), a memoir of his friendship with and translations for Joseph Brodsky, recipient of the 1987 Nobel Prize in Literature.

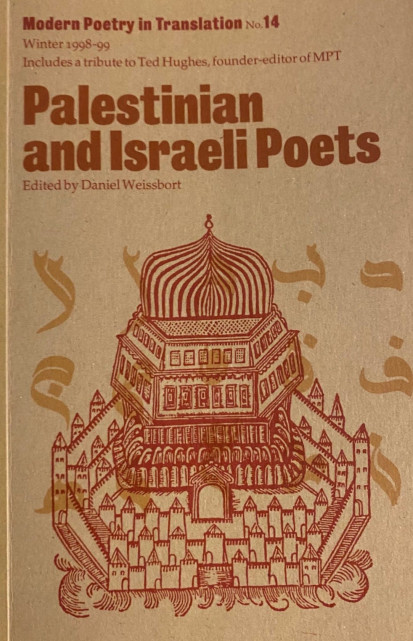

Danny died 10 years ago this month, Nov. 18, 2013, nearly a quarter century after I took his translation workshop and course on Central and Eastern European poetry and first read many of the poets who would become my heroes—Milosz, Herbert, Amichai, Szymborska. In his later years, Danny was especially proud of the Winter 1998-99 edition of MPT, titled Palestinian and Israeli Poets: Edited by Daniel Weissbort.

As he told the Guardian in 2001, “We recently did an Israeli-Palestinian issue, and it seemed just the thing that needed to be done. There are people writing in Arabic and in Hebrew in this same small area. People doubted whether the poets would do it, but I think after a while we managed to persuade them that this was an honest effort and we weren’t trying to censor anyone. We thought there was a virtue in simply bringing them together under the same cover.”

Two decades later, during a time of war and great distrust on both sides of the conflict, the virtue of that endeavor is even more apparent. Here’s another way of putting it: I don’t think Danny disagreed with W.H. Auden, when he wrote, in his often quoted and misunderstood fragment of a line from “In Memory of W.B. Yeats”: “poetry makes nothing happen.” What it does, Auden says, is “survives / In the valley of its making where executives / Would never want to tamper, flows on south / From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs, / Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives, / A way of happening, a mouth.”

The poetry of survival is not about political poetry, it’s about the humanity that survives the political. In Danny’s words, the poet follows his or her impulse to “bear witness, to ensure that the silence which engulfed those millions does not consume also the survivors. This is, perhaps, what it means to survive.

A friend and colleague of Danny’s at the University of Iowa told me recently that, in his final years, struggling with poor health, he remained as committed as ever to the work and necessity of translation, calling him often to remind him, “No matter what happens, we must save the Translation Workshop.”

I lost touch with Danny over the years but moved back to Iowa City in 2005, his home away from London for decades. It was then, strangely, that I got to know him best, not as a teacher or translator, but as a poet, through the reading of his poetry collections (most of which, sadly, like The Poetry of Survival, are out of print). So I’d like to leave you, in this time of terror and great uncertainty, with a poem of his about survival.

It’s from a thin collection titled Inscription, dedicated to his father, Maurice, and mother, Rachelle, published in 1993 as part of the Cross-Cultural Review’s Jewish Writers Chapbook series. I found the book, signed by Danny, not in any special collection, but there among the others, squeezed between Warren and Whitman. The poem, part of a series, appears near the end of the book, not far from a portrait of his mother, alone in Belgium, in 1920, on an unnumbered page:

from

Origins of Death

Death originated in the back of Man’s mind.

It held itself in readiness,

waiting to be called.

Finally, out of curiosity, Man summoned it.

It came modestly, with lowered gaze,

like a poor relative or humble petitioner.

But when at last it lifted its face,

Man saw it was laughing,

that it had been laughing all the while.

And then its laughter filled the sky, like storm clouds.

Its laughter lashed Man,

and he cowered, raising his arm to protect himself.

But nothing could protect him from this laughter’s scourge,

which traveled the length and breadth of the earth,

until at last it subsided,

having made its mark everywhere.

And Man rose again, fatally weakened,

but free at least of the burden his curiosity had laid on him.

--

Michael Judge is a poet, journalist, and publisher of The First Person with Michael Judge, a weekly Substack publication read across 50 U.S. states and 63 countries. A former arts and culture writer at The Wall Street Journal, he is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. His work has appeared in The New York Times, NPR, The Washington Post, Columbia Journalism Review, The Literary Review, The Iowa Review, Poet Lore, and Smithsonian magazine, among other publications.