A Conversation with Katherine M. Hedeen

An Interview with Katherine M. Hedeen, on her English translation of Victor Rodriguez Nuñez’s actas de medianoche as midnight minutes

Interview by Sarah Swinwood

—

Katherine M. Hedeen is a prize-winning translator of poetry and an essayist. Her latest book-length publications include Book of the Cold by Antonio Gamoneda, Every Beat Is Secret by Fina García Marruz, and Almost Obscene by Raúl Gómez Jattin, and she is a Managing Editor for Action Books and Professor of Spanish at Kenyon College. Sarah Swinwood sat down with her to discuss her translation of Victor Rodriguez Nuñez’s ‘actas de medianoche’, which is now available at Carrion Bloom Books, and which will be re-published by Action Books in 2024.

—

SS: Hi Katherine. Thank you so much for taking the time to chat with me about your translation of ‘midnight minutes’, a startlingly beautiful river of a poem described in your translator’s note as “just one long breath.” When approaching this work, was there an order of importance as to which elements were most essential to capture? Did you begin with more of an emphasis on word choice to convey meaning, or more of an emphasis on rhythm and flow? What is the first thing you focus on when interacting with such a breathtaking poem?

KMH: Hi Sarah, thanks so much for taking the time to engage with my (and Rodríguez-Núñez’s) work, and specifically midnight minutes. Just to give you some context, I have been translating Rodríguez Núñez’s poetry since the mid-90s. This has made me both an expert in and a witness to how it has evolved and changed over the years. This book, written as we moved into a new century, signals a fundamental change in his poetics. In his earlier work, poems were topical, condensed bundles of (mostly) coherent meaning with a clearly developed beginning, middle, and end; a more conventional (acceptable?) approach to poetry. As you might guess, midnight minutes rejects this in favor of strangeness and sprawl. This is precisely why it’s my favorite book of his. As I have translated it, preserving the strangeness has been my biggest priority. The poem proposes its own different–and difficult–logic. My goal with the translation has been, both in terms of content as well as rhythm and flow, to defend its radical “irrationality.” For me, this is falling under the poem’s spell, losing control of it, letting it guide me. In more concrete terms, this might look like me, as a translator, refusing to impose a “rational” meaning on a word, phrase, or verse when there is none. Or, it might look like me, as a translator, replicating the creation of different meanings through the extensive use of enjambment.

SS: You’ve done a tremendous job of maintaining the ethereal nature of the original. I am struck by so many lines in midnight minutes that display the strangeness and sprawl you speak of:

because the shadow pours those meanings

not even read by the breeze

and so many drunken frogs

would only want to jump towards the soul

You mention that midnight minutes is not only one of your favorites, but also one of his most well received works to date. Why do you think that is, especially right now?

KMH: The original book(s) (initially Rodríguez Núñez had divided the over 2000-line poem into two parts) were quite successful in Spain in the early 2000s, receiving prizes that ensured their publication. The book-length poem has now been published throughout Latin America as well, and individual cantos have been translated into various languages. We have been surprised at how well the poem has been received in the Spanish-speaking world. When it first came out, it was unlike any poetry that was being written at the time in Spanish. Not only did it signal a new poetic cycle for Rodríguez Núñez, it signaled one for Latin American poetry too. It was one of those situations where whether a reader loved it or hated it, they had to dialogue with it. actas (as we affectionately call it in Spanish) has also ushered in an incredibly prolific creative moment for Rodríguez Núñez, opening up so many ways to poetry. Since 2001, he has brought out 8 new books and countless anthologies. The success of actas was not mirrored in English. Poems from midnight minutes were floating around for years, unable to find a home in U.S. journals. They were too long and they were too weird and they didn’t exactly fit into the “American” vision of how a Latin American, how a Cuban, should write. I kept at it and, eventually, I did find a place, due in great part to Johannes Göransson and Joyelle McSweeney taking a chance on them, as part of an anthology of Víctor’s work that Action Books published in 2017, called Night Badly Written. Then, Jace Brittain and Rachel Zavecz from Carrion Bloom Books loved them too and made this beautiful chapbook. Now the full book will be coming out with Action Books next Spring. I’m so grateful midnight minutes found its readership here. Not surprisingly, it took a lot longer.

SS: What a gift to have been translating Rodríguez-Núñez long enough to become an expert and a witness. As this is a departure from his previous work, is there something that you needed to alter to tune into this current voice? Where does your translator self settle, or what techniques do you have for aligning with these simultaneous occurrences—being well acquainted with the writer, your personal evolution as a translator and this current shift in style and voice?

KMH: This is a very interesting question; thank you. Being “well acquainted” with the writer is an understatement! We have been partners since 1996, so it’s very challenging to tease out the different selves between us. We are artists together, we think together, we talk about our work and are constantly bouncing ideas off of each other. I think that, because of this, the process of altering doesn’t feel much like altering at all. It has come about very organically, for both of us. I saw these poems being born in Spanish. I know them intimately. I am IN the poems or at the very least the poet’s vision of me is. And, if I am not explicitly there, I sense that I am their ideal interlocutor, precisely because Víctor and I, outside of the poems, are also in continual dialogue. All this is to say that as artists, as writers, we are collaborators. I don’t think either of us think of our work as “chronological,” meaning that there is an original (first) and then there is a translation (second). It’s much more complex than that.

SS: Such a beautiful backstory, thank you for sharing. It adds such a profound, esoteric and intimate dimension to the work. With any translation, there is an element of entering the psyche of the original writer, a type of telepathic conversation, or a tuning-in to something beyond logic. What occurs with someone I’ve never met but whose work I engage with versus working with those I’ve spent a lot of time with and know closely has an effect on the level of interior dialogue. I much appreciate you giving us a window into the nature of this particular work. You mention that midnight minutes is “decidedly anti-national.” There is a bridge between Cayama, the sugarmill town where Rodriguez-Nuñez grew up in the middle of Cuba, and the deepening of his ties with the United States. Can you speak a little more on this?

KMH: This is actually quite complex and I can’t speak to it without speaking specifically about the context of Cuba and the U.S. But first, let me say that, in a general sense, when we leave what we know, when we are forced to go elsewhere, what first comes to us is how different things are in the new space we inhabit. This differentiation is an aspect of exile that is often highlighted, and, of course, it is all very true. But there is another side, too. In the case of Cuba, which has historically been considered the U.S.’s backyard / playground, and was a neo-colony of the U.S. until 1959, differentiation has been a key aspect of its nationalist discourse. How Cuba is “different” from everywhere else, and especially the U.S. This makes a lot of sense to me; the purpose of the emphasis on differentiation is justified. So, Rodríguez Núñez arrived in the U.S.—not as a political exile, but definitely as an economic one—and immediately saw those differences. However, as he continued to live here, he began to realize that there was a process of identification that counteracted the differentiation. Tellingly, much of this realization occurred for him, I think, because of living in mostly rural areas in the U.S. (and in particular the flora and fauna of those spaces), which brought him back to the Cuban countryside, to Cayama, the little neighborhood where he grew up in the center of the island. Through this process, he came to realize that the exceptionalism characteristic of nationalist discourse (whether it be Cuban or U.S.) was a key element of what ultimately is a destructive ideology. In this sense, his poetics have come to favor identification over differentiation and he identifies with Cuba as well as the United States.

SS: Would you be willing to go a little deeper into what it’s been like translating your husband for so many years? What does your discourse look like? Perhaps you can touch on the benefits and challenges you encounter and also how this aspect of the relationship has evolved over time?

KMH: This is a topic that is difficult for me to talk about. On a personal level, it is absolutely amazing, a total privilege, to be such a part of my partner’s poetry; to be the explicit object of desire (or sometimes anger and frustration). It’s all there. As such, it is very intimate and I am a very private person. So, as a translator, I try to disassociate. Just as the speaker of a poem is not the poet, the poetic “object” is also separate. But this doesn’t always work out. My humanness is ever present. I go through it: happiness, love, anger, sadness, jealousy.

As for challenges and benefits, I have access to a whole other level of reality (and irreality). We don’t even need to speak most of the time, I just know. I’m not just referring to content. Content is perhaps the least of it. I know what’s behind the words, the ideas, the poetics, and I think that makes me a better translator. At the same time, I often struggle for distance, for a step back, a clearer focus, a way to defamiliarize. Finding that balance is a beautiful challenge, one that will last a lifetime. But ultimately, I love the blurriness, the messiness of it; it’s where the magic is.

SS: Thank you so much for your generous answer. I appreciate you sharing this with us since it is so personal. It is beautiful to contemplate and reflect on where we as translators relate in varying ways to our subjects. Home and the natural world are being addressed with such intimacy in these poems. Some lines even take on a mythological tone, transcending space and time:

when he castrated the stars

since night keeps watch

I make the most of it and sow myself

naked in your snow

Since these were written between 2001-2005, I wonder, is there a desire to revisit or extend this love letter to home? To continue the conversation?

KMH: As I’ve mentioned earlier, midnight minutes signaled a shift in Víctor’s poetics and with it his process changed. Every book he’s written since then uses more or less the same method: taking notes in a notebook in a stream-of-consciousness kind of way and then embracing some kind of formal constraint (metered verses, the sonnet, the haiku, the décima, among others) to organize the verses and the book. In the case of midnight minutes, that constraint was the sonnet (each canto is made up of 11 sonnets and there are 14 cantos) and the use of syllabic verse (7, 11, or 14 syllables). But, strangely enough, despite such a significant change—and what could be described in many ways as a nomadic existence—what has become increasingly apparent is that Víctor has always written to and from his home, even in his very first poems. Another way of saying this is that, ultimately, his poetry is (and always has been) “a love letter to home.” The conversations haven't ever stopped. midnight minutes is just one of many.

SS: In your translator’s note you say “reader and poet share the task of meaning-creation.” I love this because is that not also part of your job as the translator? It’s as though you are inviting the reader in as a collaborator, which really breathes life into the work.

KMH: Your question makes me think of the many roles I (and translators in general) play in the process of translating. I am, first and foremost, the most dedicated and careful reader of the text I translate. And then, I am also a poet, creating the poem in the other language. So, in some ways, when I say “reader and poet share the task of meaning-creation,” I am most definitely talking about my work as a translator. But, in a more general sense, I am talking about the relationship between poetry and the reader of poetry, which, at its best, is even beyond the notion of collaboration; it is a call to dialogue. In dialogue, there is surrendering of control and an opening up to multiplicity. This suits me, both as a reader and a translator.

--

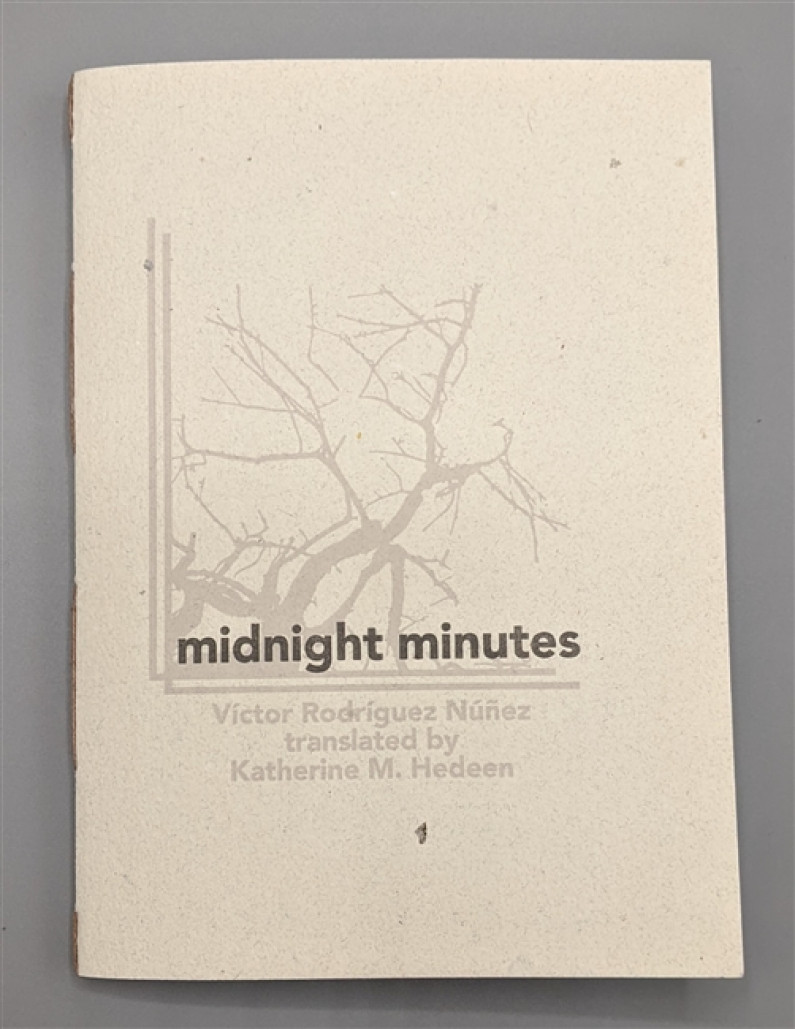

midnight minutes / actas de medianoche

by Víctor Rodríguez Núñez

translated by Katherine M. Hedeen

Designed, printed, and assembled by Carrion Bloom Books in Salt Lake City, Utah in 2022

Poetry in a bilingual edition, 59 pages

$20 - $31

Edition size: 70 copies. Presented in a tête-bêche bilingual edition. Pick up a copy here.

The poems in this chapbook will be published in a full-length book of poetry from Action Books in 2024.

--

Katherine M. Hedeen is a prize-winning translator of poetry and an essayist. Her latest book-length publications include Book of the Cold by Antonio Gamoneda, Every Beat Is Secret by Fina García Marruz, and Almost Obscene by Raúl Gómez Jattin. She is a Managing Editor for Action Books. She is based in Havana, Cuba and Gambier, Ohio, where she is Professor of Spanish at Kenyon College. More information at: www.katherinemhedeen.com

Sarah Swinwood is a writer and performer from Montreal, Canada, currently completing her double theses in creative nonfiction and literary translation at Columbia University in New York City. Sarah translates poetry from French and Spanish into English. She resides in Brooklyn where she is finishing her first collection of essays in creative nonfiction, poetry chapbooks and profiles of artists from Manhattan’s Lower East Side. She teaches creative writing and helps run a nonprofit ‘Humans in Harmony’ that brings songwriting resources to at-risk youth and incarcerated writers.