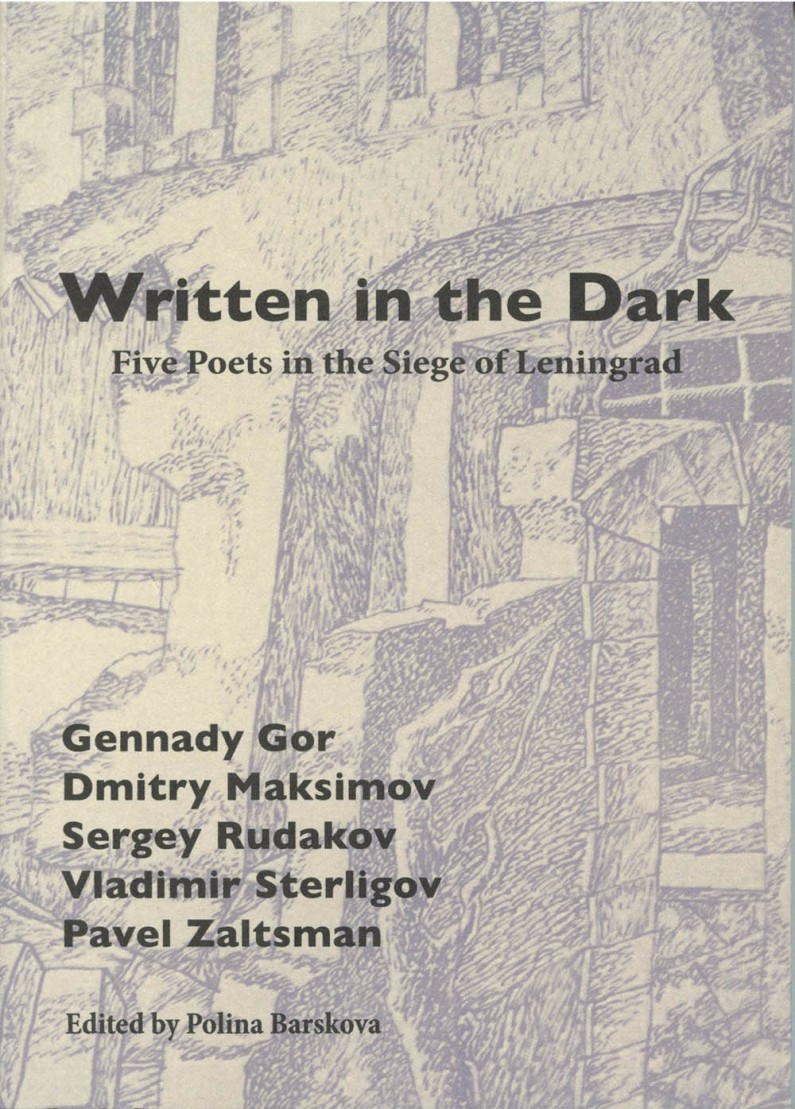

Review: Written in the Dark

Written in the Dark (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2016), a new collection of poems edited by Polina Barskova, brings immediacy to the horror of the Siege of Leningrad. These works are not only about the siege, but were written during the siege itself. The site of extended suffering, starvation, even cannibalism, the siege of Leningrad is almost unfathomable in our historical memories. This collection gives voice not only to the pain of its authors, but represents art’s attempt to combat the darkness when humanity breaks down.

The five featured poets—Gennady Gor, Dmitry Maksimov, Sergey Rudakov, Vladimir Sterligov and Pavel Zaltsman—illustrate the variety of litany and collective trauma of this historical event. The introduction describes the general wave of writing as “siege surrealism.” This style counters, as outlined in the introduction, the general narrative of postwar siege poetry, which was often used for propaganda purposes and focused on Leningrad as a heroic city. This extract from a poem by Gor illustrates a subversion of the heroic narrative:

A llama in a yellow gown sits on a chair.

He touches a rosary with his hand.

And mama’s laughing, petting his face,

She sits down on his lap.

And time keeps stretching, keeps stretching, elongating.

I am afraid to be late to the Neva for water. (31)

Reality dawns on the surrealism in this passage, the strange, comical vision of the llama and the warping of time is replaced with the immediacy of thirst. While the sense of time feels Daliesque, the image is undercut by the simple need for water. This urgency runs across through each of the poets, whether in language or image: each is writing to survive and unsure of the outcome, not a hero to be lionized. Surrealism in this context heightens the true delirium of hunger and thirst; the shock of trauma.

Barskova’s anthology draws on the work of many translators. Unfortunately, the paratext of Written in the Dark offers little insight into collaboration of the translators and their decision-making process. I felt, especially, in the Gor section—translated by Ben Felker-Quinn, Eugene Ostashevsky, and Matei Yankelevich—that I would have liked to know more about the translation choices. Take, for example, these two poems, which appear consecutively:

|

Вы немцы, не люди. |

You’re Germans, not people. |

The Russian poem is in a comic mode, undercutting the very real German threat with a ridiculous image. The English, however, does not match the meter and the curds/occurs slant rhyme feels forced and weak. The masculine/feminine rhyme scheme is also lost, which gives the English less punch. The decision to preserve the rhyme here, however, does make sense within the English-language tradition of comic verse. Rhyme can mock, as in a limerick, and make its subject ridiculous. In contrast, the next poem in the collection, also Gor, takes a different tack:

|

Какая тревога на сердце простом, Вдруг море погасло. |

How troubled is this simple heart. Suddenly the sea sputtered |

The Russian here is also rhymed, but not for comic purposes. Perhaps for this reason, the translator decided on a blank-verse approach, though the assonance is strong (wind/rivers; sputtered/butter).

This is just a small point, however, in a very beautiful, necessary collection. One of many lovely pieces, Ainsley Morse does a lovely job translating Sterligov:

|

[НА СМЕРТЬ Д. И. ХАРМСА]Даниил Иванович! Вы брали дудочку |

[ON THE DEATH OF D. I. KHARMS]Daniil Ivanovich! You took a pipe |

Daniil Kharms is the foremost representative of the lost generation of Russian surrealism, the appeal to him is particularly resonant here, as he died in 1942 from starvation during the siege of Leningrad. Sterligov’s poem brings the tragedy to the forefront, but memorializes him with a set of surreal imaginings, waking “the Russian morning,” Kharms’ giving life to a new form of Russian literary invention. This poem turns Kharms into the pied-piper of Russian verse and presents a moving tribute to the writer.

This example is one of many ways in which Written in the Dark embodies the pain and loss of an era that few historical and literary works achieve. Each act of writing feels deliberate, questioning its function within the larger strife of the time. Every line asks the artist: How can art meet the needs of a body? What can poetry do against real suffering?