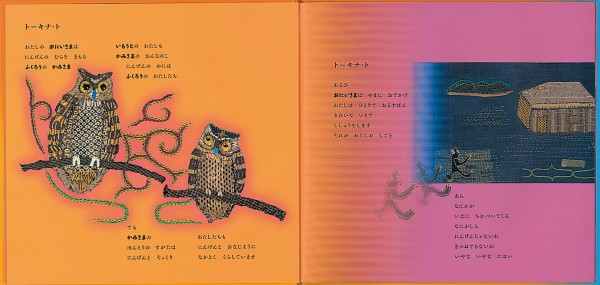

Tōkina-to

The quiet human villages

the beautiful, peaceful villages

The seas

and the rivers

are full of fish

the fields are green and ripe

The people are smiling

happy every day

protected by my Elder Brother

Tōkina-to

My Elder Brother

is the Owl God

who watches over the human villages

I, his Little Sister,

am a girl god

To the human eye

we are Owls

But

the true form of a god

is the exact likeness of a human

Like the human people

we too live happily together

Tōkina-to

One day

my Brother goes out to the mountains

and I stay at home alone

I’m doing needlework with some lovely thread

that’s what I do

Oh,

something is coming

towards the house

I wonder what it might be…

Not human, I think

Not a fox either, I think.

A horrible smell is coming

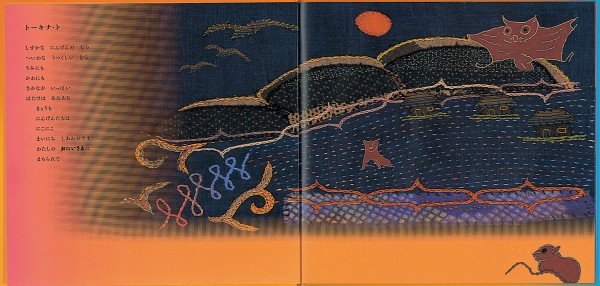

Tōkina-to

BA-BAM

Suddenly

the door opens

a nightdark Wibbly-Wobbly Man

comes into the house

I’m all alone

HELP! ELDER BROTHER!

The Wibbly-Wobbly Man

carries me away to the sea

makes me board a boat

Then

the boat travels

far, far on the ocean

Tōkina-to

Many nights

many days

far, far away

the boat travels on

Here

A sea of birds’ feathers

fuwa fuwa, hira hira, moku moku

fluffy, fluttery, fleecy

Above and below

left and right

blanketed white with white feathers

fuwa fuwa, hira hira, moku moku

fluffy, fluttery, fleecy

Oh dear,

I can’t see anything at all

Tōkina-to

Many nights

many days

far, far away

the boat travels on

Here is an ocean of bamboo

SPLOSH!

Water drumming down.

When the huge bamboo branches bend and bounce

a rush of water storms down

Over there

and over here

SPLOSH!

Water drumming down.

Lightening strikes and thunder crashes

rumble rumble rumble BANG

Tōkina-to

Many nights

many days

further and further away

the boat travels on

This is the cloud gate.

All the world’s clouds

leave from here

in the morning

all the world’s clouds

return here

in the night

Our world

ends here.

If we go past this point

we can’t go back home

I’m shivering, shaking, shivering

Tōkina-to

Elder Brother! Elder Brother!

Aah, aah

my tears are falling

drip-drop, drip-drop

Beyond these clouds

the world of demons

no more living creatures

Goodbye, my dear fish

bears

deer

Goodbye, goodbye

Aah, aah

Drip-drop, drip-drop

Even my Elder Brother’s enormous eyes

cannot see

beyond this point

Tōkina-to

And here we are

the beginning of the world of demons

the Wibbly-Wobbly Man

hoists me up

climbs a tall, tall mountain

and monsters appear

one after the other

bata bata,

flip-flaps the bird monster

kero kero

croaks the frog monster

Oh dear,

mud-clump monsters live here

yura yura,

sways the snake monster

Oh dear

one-eyed monsters live here too

Tōkina-to

We go

into a pitch-black cave

Red eyes are glowing

are they a monster’s eyes?

golden eyes are glinting too

I can also see

a mouth

with a slimy tongue

slithering out

Oh I’m scared!

So very

scared

I might stop breathing

Tōkina-to

In the end

we’ve arrived at a huge room

with the flames in the fire pit

pachi pachi,

crackling in the pitch dark

Apart from that

I can’t see anything at all

The Wibbly-Wobbly Man

puts me down

next to the fire pit

wavering and worn out

I collapse

and with a si-i-igh

I faint.

Tōkina-to

Oh!

What’s that noise?

UH-WOH-OH-OH

BAHAA BAHAA

a Demon as big as a mountain

is laughing

one of its eyes

is an eye as round as the moon

the other eye

is a tiny, tiny eye

The Demon’s face is very strange.

The Wibbly-Wobbly Man

greets it,

“Great Demon King,

as you commanded

I have brought you

the beautiful Maiden”

Tōkina-to

I’m captive to the Demon King

a number of days have passed

RUMBLE RUMBLE RRRRRIP

Oh!

Someone’s come to help me!

A white mist arises

and I am lifted up

A stern, noble voice rings out

“Demon King!

You have done such a foolish thing —

for this I will throw you down into the underworld!”

In an instant

the Demon King and the cave and the mountain

scatter into pieces

and fall down into the underworld

shudder judder CRASH SMASH

rattle RAT-A-TAT

crumble

Tōkina-to

Swooosh

A puff of wind from the white mist

blows me up

onto a cloud in the sky

and then the cloud, in one leap

sends me home

to my familiar village

Look!

I can see that white mist

up in the sky

the golden sword scabbard

glistens

That must be—yes,

the half-god

half-human

youthful hero,

Ainu-rak-kur!

Tōkina-to

I drink in the sight of

my village

my beautiful village.

My dear friends, the rabbits

the deer

the wildcats

are delighted to see me

“Welcome back!” they say. “We’re so pleased.”

I can hear the voice

of Ainu-rak-kur

“Listen well.

Your Elder Brother

was worried every minute.

Go straight back home

and be sure to tell him

exactly what happened.”

Tōkina-to

Elder Brother

worried and worried so

he had become sick

Po-ro-ro po-ro-ro

my tears plinked down

and I told Elder Brother

everything that had happened

Elder Brother

soon became well again

he said to me,

“Any God I asked for help

could not help

so, Little Sister,

I asked for help

from our young relative

Ainu-rak-kur.

Let us offer him a feast in thanks”

Tōkina-to

The preparations for the feast begin

Thump thump thump

the mallet pounds the rice into dough

we shape the dough into lots of balls

we prepare plenty of saké to drink

Everyone is busy getting ready

Elder Brother, it seems

is keeping an important secret

I ask again and again but he won’t tell

Tōkina-to

On the day of the thank-you feast

Elder Brother

says to Ainu-rak-kur

“This is a joyous turn of fate

Will you take Little Sister’s hand

in marriage?”

Ainu-rak-kur,

sparkling

approaches me with a smile

What a dazzling hero!

What a fine person!

This was Elder Brother’s secret.

Elder Brother also gifts me

a beautiful necklace

Without delay

the two of us

sit before Elder Brother

Elder Brother holds inau*, the symbol of the gods,

and prays

“May you be a happy husband and wife.”

Tōkina-to

The two of us

began to enjoy our lives together

in Ainu-rak-kur’s

castle in the mountains

The half-god

half-human

youthful hero

Ainu-rak-kur

and myself,

the Owl God’s Little Sister

live happily together

very young and well

very cheerful

to this day.

*Inau is a sacred item, said to have the gods residing within. Many are beautifully decorative, made with a piece of willow with fine strips of the wood shaven and curled into ribbons at one end.

Text: Tsushima Yūko

Original accompanied by needlework illustrations: Ukaji Shizue

Layout: Sugiura Kōhei

Fukuinkan Shoten Publishers, 2008

A Note on the Text by the Author

Ainu epic chants are a form of oral literature, and include types such as kamui yukar (mythic epics), in which the gods narrate their own experiences, and yukar (heroic epics), in which young, great superheroes vanquish one villain after the other. These superheroes appear under many different names, and Ainu-rak-kur who features in this version is one example.

Both forms of Ainu epic chants are recited to a rhythm, but kamui yukar always repeat a sakehe (refrain), such as the phrase “Tōkina-to” in this story. Unfortunately, the meaning of “Tōkina-to” is not known, but examples of refrains from other stories include, for instance, an imitation of the fox’s call in a story narrated by the Fox God, or a reproduction of the sound of thunder in a story of the Thunder God, and phrases depicting the gods’ appearances also occur. The sakehe is unique to each story. There are so many — we may say countless — kamui yukar, but these unique refrains make it possible to distinguish each one. For that reason, conventionally these stories are named after the sakehe, much in the style of a story title. In kamui yukar, the sakehe would be chanted to keep the rhythm, as in this story: “Tōkina-to / The quiet human villages / the beautiful, peaceful villages”.

Kamui yukar encompass the feeling of the gods being present in every part of the natural world that humans encounter in their daily lives as well as the desire for humans to coexist with these gods. When on earth, these gods may take the form of animals, birds, plants, water, or air, but when in the heavens they are seen to take the same form as humans and live as they do. As such, within this worldview, if a human hunts this body in its earthly form, and offers the correct prayers to send its spirit to the heavens, then a new body will be brought back to the earth for people. Conversely, if the gods are angered by prayers being incorrectly offered, they will no longer come to the earth for humans.

The narrator of this story is a shimafukurō - Blakiston’s Fish Owl: a huge type of owl with a wingspan of up to two metres (about 6.5 feet), found only in Hokkaido. These owls have been revered by the Ainu people as the gods who protect the villages, but in recent years their habitats have dramatically reduced and it is feared they will become extinct.

The story here is based on the kamui yukar listed as Myth 59, told by Hiraga Etenoa (Date of recording: 2 September, 1932, Place of recording: Shinpiraka Village, Saru District, Hidaka Province) in Kubodera Itsuhiko’s Ainu Epic Chants: A Study of Kamui Yukar and Oina (Ainu jojishi: Shin’yō, seiden no kenkyū published by Iwanami Shoten, 1977). However, in order to write in the style of a picture book for children, I have purposefully condensed parts and made the language more easily understandable; for this I beg your understanding.

トーキナ・ト

しずかな にんげんの むら

へいわな うつくしい むら

うみにも

かわにも

さかなが いっぱい

はたけは あおあお

きょうも

にんげんたちは

にこにこ

まいにち しあわせです

わたしの おにいさまに

まもられて

トーキナ・ト

わたしの おにいさまは

にんげんの むらを まもる

ふくろうの かみさま

いもうとの わたしも

かみさまの おんなのこ

にんげんの めには

ふくろうの わたしたち

でも

かみさまの

ほんとうの すがたは

にんげんと そっくり

わたしたちも

にんげんと おなじように

なかよく くらしています

トーキナ・ト

あるひ

おにいさまは やまに おでかけ

わたしは ひとりで おるすばん

きれいな いとで

ししゅうをします

それが わたしの しごと

あら

なにかが

いえに ちかづいてくる

なにかしら

にんげんじゃないわ

きつねでもないわ

いやな いやな におい

トーキナ・ト

ばったああん

とつぜん

とが ひらきます

まっくろな ひょろひょろぼうずが

いえのなかに はいってくる

わたしは ひとりぼっち

たすけて! おにいさま!

ひょろひょろぼうずは

むりやり

わたしを うみまで はこび

ふねに のせます

そして

うみの

とおくに とおくに

ふねは すすみます

トーキナ・ト

たくさんの よる

たくさんの ひる

とおくに とおくに

ふねは すすむ

ここは

とりの はねの うみ

ふわふわ ひらひら もくもく

うえも したも

みぎも ひだりも

しろい はねで まっしろけ

ふわふわ ひらひら もくもく

これじゃ

なにも みえないわ

トーキナ・ト

たくさんの よる

たくさんの ひる

とおくに とおくに

ふねは すすむ

ここは たけの うみ

びっしゃん ざざざざざ

びっしゃん ざざざざざ

おおきな たけが はねると

あらしのような みずが ふってくる

あっちでも

こっちでも

びっしゃん ざざざざざ

びっしゃん ざざざざざ

かみなりも おちてくる

どどどどどど どかあああん

トーキナ・ト

たくさんの よる

たくさんの ひる

ますます とおくに

ふねは すすむ

ここは くもの もん

あさ ここから

せかいじゅうの くもが でかけて

よる ここに

せかいじゅうの くもが もどります

わたしたちの せかいは

ここで おわり

このさきに いったら

もう かえれない

ぶるぶる がたがた

わたしは ふるえます

トーキナ・ト

おにいさま! おにいさま!

ああん ああん

ぽとん ぽとん

わたしの なみだが おちる

くもの むこうは

まものの せかい

いきものは もう いない

さかなさんも

くまさんも

しかさんも

さようなら さようなら

ああん ああん

ぽとん ぽとん

おにいさまの おおきな めにも

ここから さきは

もう みえません

トーキナ・ト

いよいよ

まものの せかいが はじまります

ひょろひょろぼうずは

わたしを かついで

たかい たかい やまを

のぼります

ばけものたちが

つぎからつぎに あらわれます

とりの ばけものが ばたばた

かえるの ばけものが けろけろ

どろの かたまりの ばけものも いるわ

へびの ばけものが ゆらゆら

めが ひとつの ばけものも いるわ

トーキナ・ト

まっくらな ほらあなに

わたしたちは はいります

ぎらりぎらり

あかい めが ひかる

ばけものの めかしら

きらりきらり

きんいろの めも ひかる

にょろりにょろり

べろの のびた

くちも みえる

ああ こわい

こわくて

こわくて

いきが とまりそう

トーキナ・ト

さいごに

ひろい へやに つきました

いろりの ひが

ぱちぱち

まっかに もえている

ほかには

なにも みえないわ

ひょろひょろぼうずは

いろりの そばに

わたしを おろします

わたしは

ふらふら くたくた

たおれて

ふうううう

きを うしないました

トーキナ・ト

おや

あれは なんの おと?

うおほおほおほお!

ばあばあばあ!

やまのように おおきな

まものが わらっている

かたほうの めは

おつきさまみたいに まんまるな め

かたほうの めは

ちいさな ちいさな め

まものの かおは とても へん

ひょろひょろぼうずが

あいさつをします

「いだいなる まおうさま

ごめいれいに したがい

この うつくしい ひめを

つれてきました」

トーキナ・ト

まおうに つかまって

なんにちも たちました

どどどどど ばりばりばり

おお

だれかが たすけに きてくれた!

しろい もやが あらわれ

わたしは だきあげられました

けだかく きびしい こえが ひびく

「まおうよ!

こんな ばかなことをする おまえは

じごくに おとしてやる!」

たちまち

まおうも ほらあなも やまも

ばらばらになって

じごくに おちていきます

ぐあらぐあら どばんどばん

ばばばばば

ががががが だだだだだ

トーキナ・ト

ぷううううう

しろい もやから

そらの くもに

わたしは ふきあげられて

それから くもは ひとっとび

なつかしい むらに

わたしを もどしてくれました

ああ

しろい もやが

そらに みえるわ

おうごんの かたなの

さやが ひかっている

あれは そうよ

はんぶん かみさま

はんぶん にんげんの

としわかい えいゆう

アイヌラックルさまだわ!

トーキナ・ト

わたしの むら

うつくしい むらに

わたしは みとれます

なかよしの うさぎさんも

しかさんも

やまねこさんも

わたしを みて おおよろこび

よかったね おかえりなさい!

アイヌラックルさまの

こえが きこえます

「よくおきき

おにいさんが ずっと

しんぱいしています

すぐ いえに もどって

なにが おこったか

じぶんで ちゃんと

おはなしするんですよ」

トーキナ・ト

おにいさまは

しんぱいで しんぱいで

びょうきに なっていました

ぽろろ ぽろろ

わたしの なみだが こぼれます

おにいさまに いままでのことを

くわしく おはなし しました

すぐに

おにいさまは げんきに なって

わたしに いいました

「どんな かみに たすけを

たのんでも だめだった

だから いもうとよ

しんせきの わかもの

アイヌラックルに

たすけを たのんだんだよ

おれいに ごちそうをしようね」

トーキナ・ト

ごちそうの したくが はじまりました

とんとんとん

おもちを つきます

おだんごを たくさん つくります

おさけも たっぷり よういします

みんな おおいそがし

だいじな だいじな ことを

おにいさまは かくしているみたい

いくら きいても おしえてくれません

トーキナ・ト

おれいの ごちそうの ひ

おにいさまは

アイヌラックルさまに いいました

「これも なにかの ごえんです

いもうとと けっこんしてくださいますか」

ぴかぴかぴか

アイヌラックルさまが

えがおで わたしに ちかづいてくる

なんて まぶしいかた

なんて りっぱなかた

これが おにいさまの ひみつだったのね

きれいな くびかさりも

おにいさまから いただきました

さっそく

わたしたち ふたりは

おにいさまのまえに ならびます

かみさまの しるし イナウ★を もって

おにいさまは いのります

「しあわせな ふうふになりますように」

トーキナ・ト

アイヌラックルさまの

やまの おしろで

わたしたち ふたりは

たのしく くらしはじめました

はんぶん かみさま

はんぶん にんげんの

としわかい えいゆう

アイヌラックルさまと

ふくろうの いもうとかみの わたしは

いまも

とても わかくて げんきに

とても なかよく ほがらかに

くらしています

★イナウは、神々がそこに宿るとされる神聖な道具。多くは柳の木で作り、白い木肌を薄く削り、ひとつひとつを巻き上がらせることで美しい飾りとする。

文:津島佑子

刺繍:宇梶静江

構成:杉浦康平

2008年5月31日発行

福音館書店

【解説】

⦿口承文芸であるアイヌ叙事詩には、神々が自分の経験を語る内容のカムイ・ユカラ(神謡)と、若者のスーパーヒーロー(さまざまな呼び名があるが、本編に登場するアイヌラックルもそのひとつである)が悪者たちを次から次に退治する、勇壮長大なユカラ(英雄叙事詩)がある。

⦿両方とも一定のリズムをつけてうたわれるが、カムイ・ユカラのほうは、本編の「トーキナ・ト」のような「くり返し(サケヘ)」が必ずつく。

⦿残念ながら、「トーキナ・ト」の意味は不明だが、たとえば、キツネの神が語る場合はキツネの鳴き声をまねたり、雷の神の場合はその音を模写したり、あるいは、神々の姿を描写する場合もある。そしてサケヘは絶対にほかの物語とダブることはない。無数と言っていいほどカムイ・ユカラの数はあるが、サケヘによってそれぞれの物語を区別することが可能になるし、そのため、物語のタイトルのように、サケヘでカムイ・ユカラのひとつひとつを呼ぶ習慣がある。

⦿本編の場合で言えば、「トーキナ・ト、しすかな にんげんの むら、へいわな うつくしい むら、‥‥」というように、リズムをとるため、サケヘを必ず入れて、実際のカムイ・ユカラはうたわれる。

⦿人間の生活と関わりのある自然界のすべてに神々の存在を感じ、その神々との共存を願う人間の気持が、カムイ・ユカラには込められている。動物にしろ、鳥にしろ、あるいは植物、水や空にしろ、地上ではさまざまな姿をしていても、天上で過ごす神としての姿は人間と変わらず、人問と同じように暮らしている、とされる。したがって、その体を人間が狩猟しても、正しく祈りを捧げて、魂を天国に送れば、また新しい体を地上に持ってきてくれる、逆に、祈りを捧げずに怒らせてしまうと、二度と地上に来てくれなくなる、という考え方が成立することになる。

⦿本編の語り手であるフクロウは、北海道にのみ生息する、羽根を広げればニメートルにもなる巨大なシマフクロウである。村の守り神としてアイヌのひとたちは大切にあがめてきたが、近年、生息数が極端に減って、絶滅が心配されている。

⦿なお、本編は久保寺逸彦編著『アイヌ叙事詩 神謡・聖伝の研究』(岩波書店 1977)に収録されたカムイ・ユカラ(神謡59、伝承者:平賀エテノア、採集時:昭和7年9月2日、採集地:日高国沙流郡新平賀村)をもとにしていますが、子ども向けの絵本の文章にするため、かなり思いきって省略したり、わかりやすい言葉に言い換えなければならなかったことをご理解いただけますようお願いいたします。

津島佑子