An Interview with Roy Chicky Arad

Roy Chicky Arad is a poet, activist, musician, journalist, and creator/editor of Israeli literary journal Maayan. His multifaceted body of work includes poems, prose pieces, news articles, political performances, pop songs, and translations. He has published eight books of poetry and prose, one of which, The Israeli Dream, was named one of the most important Israeli books of the 21st century by Israeli website Mako. In November 2019, the University of Notre Dame’s Creative Writing Program hosted Roy Chicky Arad for a poetry reading and workshop with the MFA students during his stay in Iowa City as a resident writer at the 2019 Fall Residency of International Writing Program, courtesy of Fulbright. Once Chicky was back in Israel, PJ Lombardo and I were able to video chat with Chicky and interview him about his visit to the United States and various other topics —his literary journal Maayan, The Coffee Book which he published in Iowa City, amoebas, punk music, and translation.

PJ Lombardo: How did you start Maayan? Did you see a need for this journal in the literary world?

Roy Chicky Arad: We started it in 2005. Before, the poetry scene in Israel was very much like a desert with a few oases, there were a handful of excellent poets like Aharon Shabtai and Efrat Mishori. In 2005, three new magazines started all at once: Mita’am, Ho!, and Maayan. It marked a new revival of Israeli poetry. Ho! was into classic poetry with rhyming. Mita’am was very political and very serious, pessimist, and psychological. Maayan is also political, but it’s more optimistic, I think. It’s happier, more colorful and experimental. Today there are many more magazines, like Dhak and Hava Lehaba. These different magazines are like different political parties. Everybody can choose a place or two to be. In the 90s, it was very cool to have a punk band and to buy an electric guitar. I also had a band in the 90’s. Before 2005, to be a poet was kind of old and awkward thing to do, like macramé. After that year, if a young girl or a young guy was coming to Tel Aviv, it was very cool to write, to be a poet. It was something you could talk about when you were on a date. There was some fighting between different groups. It was so fun.

PJ: That sounds like punk music for sure.

Yes, it was very much like Rock ’n’ Roll. I frequently got into trouble with people who preferred classical poetry over what we were doing at Maayan. Maayan made us look a bit like clowns, like a joke. It’s a compliment. I believe in jokes. I think a lot about the connection between jokes and poetry. I think the difference is jokes always have a punch line, and poetry is like a joke without a punch line. What I like the most about jokes is their beginnings. The endings can be disappointing. I think that poetry is like a joke that falls to the ocean, like a wet sock full of salty water. But coming back to Maayan, we define ourselves like a shop window for young poets. People can start their poetic career with our magazine. We thought of Maayan as a place for the people who were told that their work was not up to the standards of other magazines. We published the kind of poetry other magazines wouldn’t even want to look at. These are the poems we need. Poetry that is told to be not in “good” taste, the embarrassing poetry.

We print between 3,000 and 4,000 copies of Maayan’s every issue. Not only poetry, we also publish prose and art. I don’t like how the definitions of poetry, prose and non-fiction work. It’s not so important. That’s more for the use of shelving or for the use of bookstores. As for us, we always mix everything. This is part of our ethos; everything is a mix of everything anyway.

Rebecca Gearheart: Considering how widely Maayan is distributed relative to the number of Hebrew-speakers in Israel, we’re interested to know how the editors of Maayan see their responsibility?

No responsibility!

RG: But you can’t deny that you all edit a very prominent literary journal in Israel in a language where there aren’t as many platforms for literary work to be seen.

Our luck is that we still haven’t been discovered by the Israeli academia. Poets? The academy prefers them dead or like a very cold corpse. We are alive and too hot. A friend of mine tried to write about my work for his PhD at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, about humor in poetry, and the professors recommended that he better not mention us, that we aren’t part of the cannon. I’m pretty proud of this. The academia is very rigid in Israel. For them, we’re still the weird poets, or maybe not even poets. Though the truth is that there is no mainstream in Israeli poetry, and the academia itself is esoteric like us in our Neo-liberal era. So, we have no responsibility. There are people in the poetry scene who would be happy if every magazine becomes like ours. But I think if other magazines and poets imitate Maayan, I would close it immediately. I feel sometimes that Maayan is for the people who don’t like poetry. The people who really really like poetry, mostly hate Maayan. Or pity us.

PJ: Are you starting to see what Maayan is doing aesthetically reflected in the larger literary community in Israel?

Yes. I think also the old style of magazines is disappearing step by step. People aren’t interested in older forms of publishing. It’s important to add that the Israeli poetry scene is not only about poetry magazines or about Maayan. Ars Poetica, a group of Mizrahi poets founded in 2013, has become very popular and influential. They organized large scale political poetry events and are considered very controversial. They have a strong influence. In Europe, when I go to festivals, the crowd is mostly old and relaxed. In Israel it’s different. Nowadays poetry has become important again for young people. It has a political and social role again.

RG: Maybe the word “responsibility” isn’t right, but the journal has an undeniable influence on young writers. How do you navigate being in a position where you are editing a journal that has that influence?

We do have a certain influence, which is maybe bad, maybe good. I’m always afraid I’m doing a bad thing with my optimistic intentions. I’m always afraid that Maayan’s existence will close the way for the younger generation to make something of their own. Maybe they aren’t putting a magazine out because they know they can be published in Maayan. I think a lot about when to stop publishing the magazine. What if Maayan starts to be boring at some point? I hope when the time comes, I’ll be brave enough to close it. Will it be forever or not? Maayan has been fifteen years of my life so far.

RG: A lot of people start these journals with the idea that they will last forever, not thinking of the journal as having a lifespan. People can have a fixation on permanence in the arts.

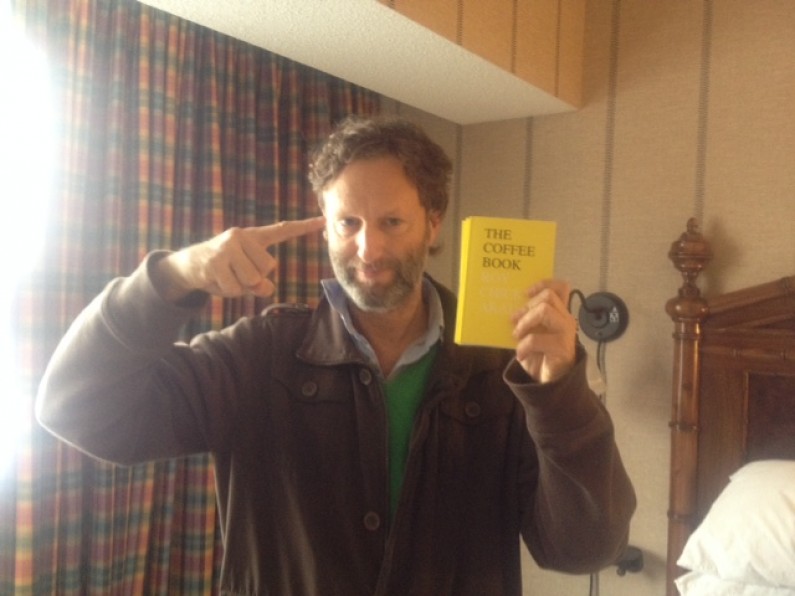

I think we keep publishing Maayan because it’s not much work and we enjoy it. The thing I enjoy most is going to the shops and giving them the new issues. I think this is something of the East-European Jew in me. I go to these shops with my shopping wagon full of magazines. I like the idea of these people who go from little town to little town with a bag of books to sell. This is how we market it. I do it with some friends. We go to stores, to kiosks, to secondhand shops. There are two chains of bookstores in Israel and we don’t sell there because they’ve really hurt the independent bookstores and small presses. After we made this decision, a lot of other small presses decided not to sell to these two chains, too. Because we don’t sell in those chains, we do everything ourselves. We compensate by selling in kiosks and bars. Or flower shops, hummus places, cafes. We started to sell in a lot of vinyl shops because there’s a connection between vinyl and poetry. There are a lot of new vinyl shops for hipsters in Tel Aviv. I really enjoy when a new issue comes out because I can go to these shops with my small bag full of magazines. I enjoy this more than editing. The editing part of being an editor is not as interesting, it’s just choosing, and I don’t enjoy saying no to people. People in Israel admire the role of the editor, but I prefer the small salesman. When I published The Coffee Book in the United States, I did the same thing. In Chicago or Iowa City, I went to coffee places and asked them to sell the books there.

PJ: We wanted to talk more about The Coffee Book.

We did the first edition, me and the editor Chamini Kulathunga, in Iowa City. I wanted to do the first edition very fast so we could do a launch party for my friends in the International Writing Program. The party was just as important as the book. The whole process took fifty days from the idea to the party.

It’s lucky we printed only 100 copies. The first edition always has mistakes, but most people may not see them. There was a problem in the Czech translation, for example. The word “stat” should have an accent on the ‘a’ that disappeared in the process. It’s a very weird book because me and Chamini edited a book in 60 languages that we mostly cannot read. It’s like being a blind editor. For this reason, there were a lot of mistakes in the first edition. And I’m sure there are mistakes in the second issue as well.

I always believed in doing things fast. I prefer doing things fast to doing things well. I really believe in the punk style of do-it-yourself and do-it-fast, and that there is some quality in urgency and a certain type of negligence. It keeps the art from being polished and too consumable. A lot of the things I do receive criticism because of that.

In Israel, we did a few instant anthologies with friends, for example, the anthology Get Out which was against the war in Gaza in 2009. We wanted to publish the project when the war started, to stop it. Antiwar anthologies are often published after the war is finished. Then people can say, “Oh, it was a very stupid war.” Why didn’t they say this before, when the war started? So, we wanted to do it very fast, when the war was at its height. But then people say, “Oh there is a mistake, a very little mistake on page twenty-eight.” But the war is the big mistake. You think a wrong letter is a mistake? So, I think it’s always good that there are some mistakes. Human beings came to being because of mutations in unicellular organisms, and then from primates. If a lot of mistakes happen together over many years, they become correct. Humanity exists because of mistakes. If there were no mistakes, we’d still be unicellular organisms or amoebas. The amoeba thought of herself as perfect, but then there was an amoeba with a mistake and another amoeba with another mistake, and then they had sex. This is the world. So, I really love mistakes.

I didn’t like poetry when I was young. I was in a band. I’m more a punk than a poet. I started poetry as a joke. For me, the most serious thing is to do things fast, to make mistakes, to do things connected to our stupid life.

RG: What was the process like working with so many people for this book? I remember this book got printed only a few days before you left for Israel. It was a very chaotic experience. What was it like to work with all these people and translators, and finding them on short notice?

We were this group of writers at IWP from all around the world. This is why I started it. I’ll read the poem:

"The coffee sits above the saucer.

Under them, the table,

under it, the country."

At my first reading in Iowa City, I read it in Hebrew, Arabic, and English. And then I looked at the audience and thought, we have so many people who speak so many languages in our group, why not use this and make a book with all these languages? Why English and not Chichewa, the language from Malawi? So, I went on Facebook and put out a call for entries. I didn’t do much work. I could have found more translators if I did it professionally and sent letters to embassies, for example. But I wanted to do it incidentally, not too professionally.

We found forty languages for the first edition. It was a very interesting process. For example, with the Polish translation we had two very good translators. One was Michael Hendelzalts, who was the editor of the Israeli review of books for Haaretz for years, and the other was Kasia Szymanska, a professor of Slavonic languages from Oxford. Two very intelligent people. And they had very different translations. I wanted them to do a co-translation, because it would be weird to have two different translations for Polish. It was really interesting seeing them talk to each other over email about how to translate this poem that was actually very short. I mean, how many words are in this poem in Polish? Ten? They exchanged long emails back and forth on how to translate this poem to Polish, a language that I don’t speak, but I know one Polish song from my Grandmother, Ada. Then they came up with a new translation. I think this process is more interesting than the book itself.

It was interesting with the Eritrean translator to Tigrinya, Samuel Menghesteab, too. In his first attempt, he wanted to improve the poem, to put into the context of a family. Because he said in Eritrea, you don’t drink coffee without a connection to family, that drinking coffee is nearly about a four hour ceremony, not the drink itself. And that you need a stove. So, I told him he could bring the family and the stove in because the translation is his work. I gave the credit to the translator on every page because the translator is writing the poem again. What does the original really mean? The original is a glass of coffee, not a text about a glass of coffee. But at the last minute I asked Samuel, “Are you sure?” and he changed it to more conventional translation. Now I think it would have been better if he improved and changed the poem. Translation is always lying. Any word is different in other language. For example, in Hebrew table is “shulkhan,” which is very different than table. It has such different letters, different connotations. With Shulkhan you think about sending something or even a sword or skin. It’s so different from table, which is more square. Translation is always a deviation from the original. So why didn’t I let him put in the family and a nice warm stove? Now I’m very sad it’s not in the translation. This might be the biggest mistake that I made, that I asked him if he was sure. It was my mistake as an editor.

I checked Wikipedia for the most popular languages, and number five was Bengali. I went through a lot of trouble to find a Bengali speaker. It was very important. If we didn’t find one, it would disappoint 230 million people. I found someone in the end, a graduate student from Bangladesh studying at the University of Iowa, Tunazzina Binte Alam. I think this entire project was thinking about cosmopolitism, especially in these days of Trump and Brexit. It’s an anti-cosmopolitan time. When we did the launch party in Iowa City, everybody read this poem in their own language. It was very beautiful. It was like a festival of voices.

PJ: In terms of peoples’ rigid identities, do you think that through translation there’s an opportunity to add some fluidity to peoples’ lives?

I hope my book will make things more fluid and open, but I’m always afraid that in my attempt to do something good, something bad might happen. I think it’s a very modest project, a very small book with a yellow cover. It won’t change the world. I hope it won’t hurt too much either. I think the book itself is very optimistic. It looks very cute, the book’s design. People in Iowa City liked the colors Yellow and black because they are the colors of the college football team, the Hawkeyes’ colors. I don’t think it was the intention of Avi Bohbot, the designer, but people ended up liking it for that reason.

RG: Can I ask you a question about the launch party for the book in Chicago that we went to? I saw you read twice in the Midwest, but the Chicago performance was really special. I’m thinking about your poem “I Vanunu.” I have a few questions about your style of reading and your style of performance, but specifically I want to talk about the experience of hearing you perform that work, of watching people dance to this poem. It was very surreal to watch it unfold, to hear you reading this work to a disco beat to a room full of people dancing. How did that performance develop, and the piece itself?

As I said before, I really worry that the things I’m doing will have the opposite effect that I want. But I think the best effect you can have is to make people laugh, to make people dance. These are two things that could never hurt anybody, I hope. So yes, it was very surreal.

RG: I don’t know if everyone realized what they were dancing to?

Vanunu was the guy who discovered in 1986 that the Israeli government had atom bombs. The Israelis put him in jail for eighteen years, at least eleven spent in solitary confinement. Now he cannot leave Israel. He cannot talk with foreigners. His secrets are very old. He was working there thirty years ago, before the invention of laptop or cellular phones. The whole world knows that Israel has atom bombs. Israel wants to drive him crazy. The bottom line is atom bombs are bad. It’s better not to have them, and if you do have them, it’s better that the world knows it. So, the life of the citizens can be safer. The system made him an enemy of the public. This poem, this song, is a happy pop song about him. I released it on an album called I Vanunu fifteen years ago, and even made a video in the Palestinian city of Ramallah for that song. In Israel, they made him look like an enemy of the public. But why? Who did he hurt?

RG: So your performance is supposed to be unsettling?

The song or musical poem is about this guy who was doing very normal things like eating schnitzel and becoming tired. Israelis behaved as if Mordechai Vanunu was a monster, the worst traitor in Israeli history, when what he did —oppose nuclear weapons—is the most normal and natural thing someone could do, as natural as becoming tired after eating lunch. What did he really do? That’s what this poem is about. I like pop music and putting pop music with something that is very political is not standard. I like to use danceable songs to talk about things that are very far from the consensus, to talk about questions that people afraid to ask. I think this has made me a very unsuccessful pop singer.

PJ: What is the relationship specifically between poetry and music?

If I need to define my lifestyle, I’m not really a poet. I’m also not a real musician. I’m a Chicky. Because I have this nickname, I want my work to be Chicky or Chickian. I like to do a lot of things. Some of my poems start as music, some of my music start as something closer to poetry. A lot of my poems were recorded with a French musician, Chenard Walcker. His real name was Yann Chenard and he died ten years ago, very young. He didn’t use any instruments, he just used samples, things he found on cassettes or things he downloaded. He took things apart and put them back together, making music. So, when people hear me, they recognize these parts. Our connection started when I put some poems of mine on the internet, and he stole them. I believe words should be free, that they are more important than us.

RG: Are you working on any new music projects right now?

Not much. I have this ukulele here, and the stylophone. I love my stylophone. I had an interesting show this week called “Wake Up Chen”, a performance for four days that Ariel De Lion arranged for a friend, an artist named Chen Cohen, who is a bit sick. It was between magic, music, and health care. So, I played and read some poems. It was a nice gig. I always work on many things. I’m a journalist, that’s how I make a living. I’m always doing poetry and music and journalism, always many things going on at the same time.

RG: Is there anything you want to talk about that we didn’t get to?

No, the questions were nice. When I was in America, I didn’t miss Israel much, and now that I’m in Israel, it’s like all my three months in the United States disappeared. But now I see you on the computer screen, so I miss America for the first time. I miss the dance clubs in South Bend, Indiana, Vickies! I miss Vickies! And that I spent half my time in Indiana looking for an electric adapter that was lost in some station. It was like trying to find a translator.

Interviewers

Rebecca Greenes Gearhart is a writer from New York currently living in Indiana, where she is an MFA candidate at the University of Notre Dame. Her fiction has appeared in The Hunger and American Chordata.

PJ Lombardo is a poet and essayist from northern New Jersey. He’s an MFA candidate at the University of Notre Dame and works as a publishing assistant for Action Books. His work is forthcoming from or has recently appeared in Dream Pop, Protean and Homintern.soy. Currently he is working on his first full book-length collection, Pusher.